On October 15th, 1918, Adolf Hitler, a Meldeganger or Company runner with the 16th List Regiment, was stationed in the war devastated Belgium town of Wervicq-Sud on the River Lys.

The ruins of Wervicq-Sud,on the River Lys, in 1918

As the German army fell back in disarray, under a British assault, Hitler’s final hours of battle involved carrying urgent messages to and from its beleaguered commanders.

Hitler as a Meldeganger (Company runner) with the 16th List Regiment

The Day Hitler’s World Went Dark

Early on the morning of October 15th , Hitler was among other soldiers gathering around the smoky stoves of a hastily set-up field-kitchen, in an abandoned gun emplacement, where company cooks were serving exhausted troops their first hot meal of the day.

Ignaz Westenkirchner, one of Hitler’s fellow Company runners, described what happened next.

‘Not long after they had started eating, artillery fire began and before the men fully realised what was happening blasting grenades mixed with gas grenades were raining down, one gas grenade detonated with the well-known dull thump immediately in front of the army kitchen and the old gun-emplacement respectively.

The cook screamed ‘gas alert’ but it was too late. Most of the comrades had already inhaled the devilish mixture of the Yellow Cross grenades (Gelbkreuzgranate) and stumbled away coughing and panting.

They hardly made it back to the bombed-out house, in whose cellar they had been living, when they began to lose their eyesight and the mucous membranes in their mouths and throats became so inflamed that they were unable to speak.

Their eyes were terribly painful; it was as if red-hot needles had been stuck into them. On top of that, their eyes would no longer open, they had to lift their eyelids by hand only to discover that all they could make out were the outlines of large objects.

Six of them, among whom was Adolf Hitler, scrambled to the assembly point for casualties, where they lost contact with one another due to their blindness… Hitler ended up in Pasewalk in Pomerania. The war had ended for all of them.’

How Hitler Remembered the Attack

His account, recorded in the early ‘thirties, closely echoes Hitler own version of events in his autobiography Mein Kampf (My Struggle).

‘On the night of October 13, the English gas attack on the southern front before Ypres burst loose.

They used Yellow-Cross gas, whose effects were still unknown to us as far as personal experience was concerned. In this same night, I myself was to become acquainted with it.

On a hill, south of Wervick [sic], we came on the evening of October 13 into several hours of drumfire with gas shells which continued all night more or less violently. As early as midnight, a number of us passed out, a few of our comrades forever. Towards morning I, too, was seized with pain which grew worse with every quarter hour, and at seven in the morning I stumbled and tottered back with burning eyes; taking with me my last report of the War. A few hours later, my eyes had turned into glowing coals; it had grown dark around me.’

German infantry under a gas attack in 1918

Errors in Hitler’s Story

Hitler’s account is inaccurate in two respects: the first trivial, the other of considerably greater significance.

First the minor error.

Hitler got the date wrong. The attack occurred on the morning of the 15th October, not the 13th as he states.

Given the frenetic conditions under which he had lived during his last few days on the front line, his physical and mental exhaustion prior to the attack and his parlous health immediately after it, such minor confusion is hardly surprising.

When dictating his memoirs to Rudolph Hess, while in Landsberg Prison, he had no access to military or medical records and had to rely solely on his memory.

What Type of Gas Was Used?

The more crucial error lies in his description of the gas used.

He claims it was ‘Yellow-Cross’, or mustard gas. Yet Hitler’s medical notes make no mention of a specific gas.

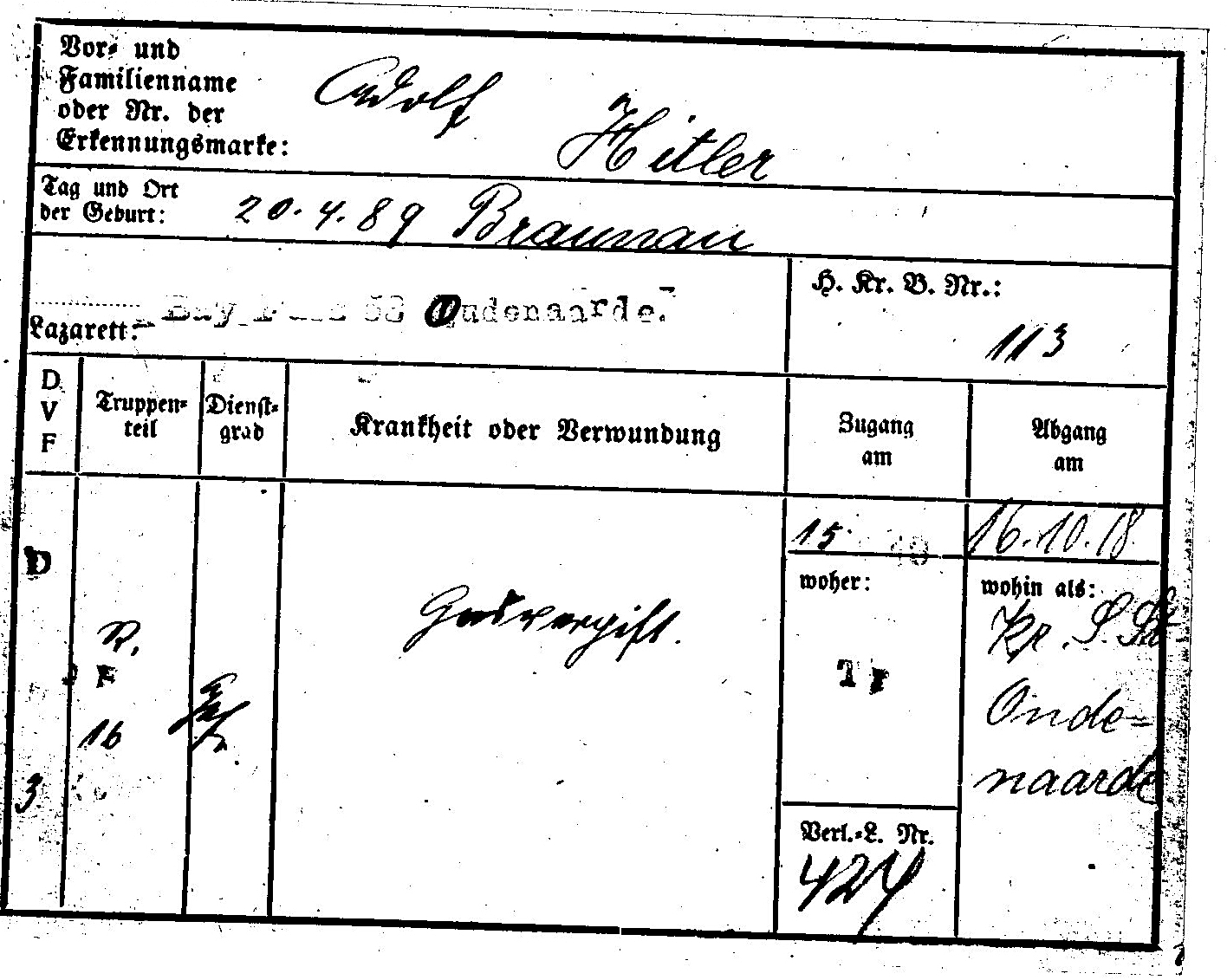

The doctors who examined him, at the Oudenaarde hospital in Belgium, described his condition simply as due to ‘gasvergiftet‘ (gas poisoned).

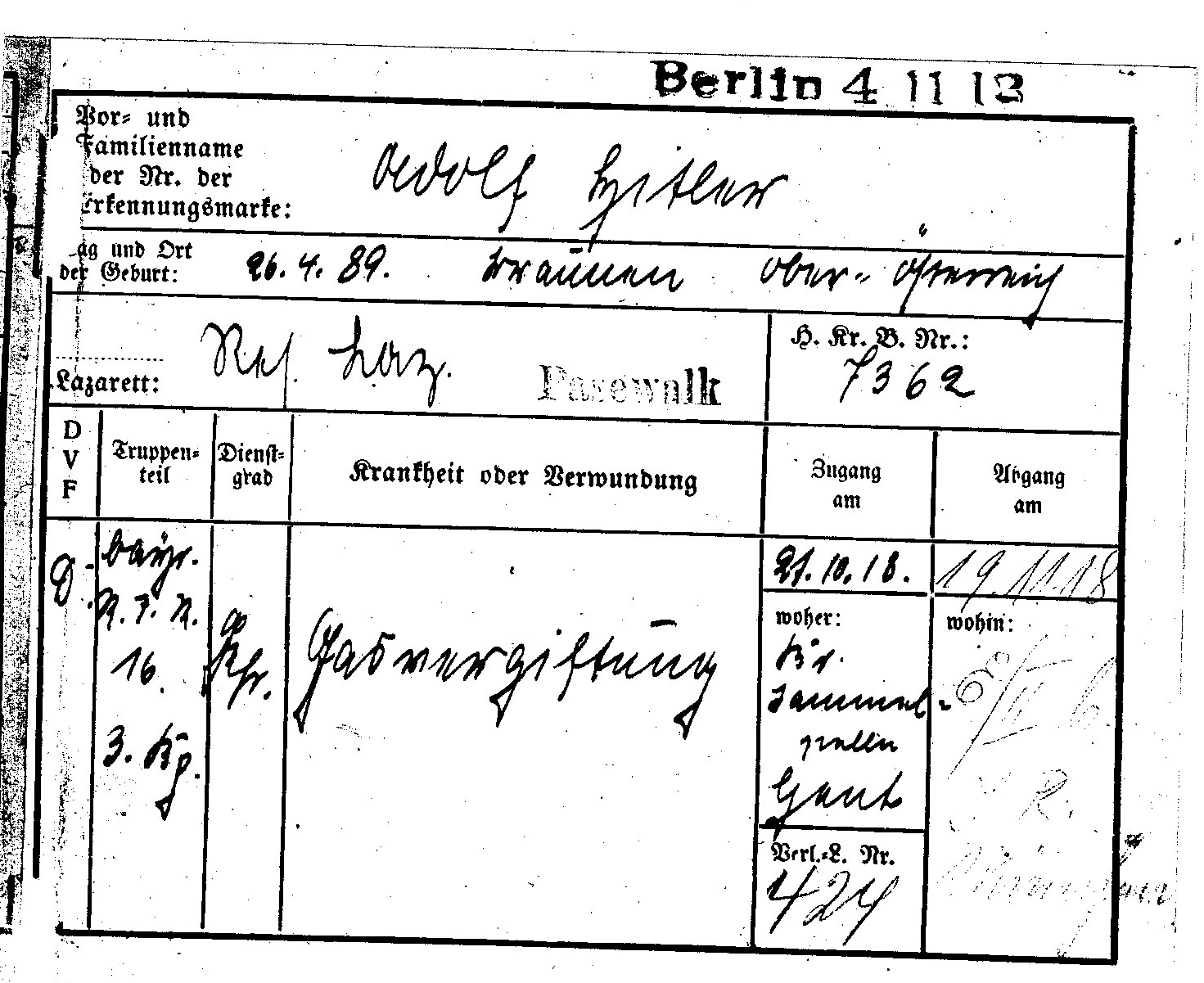

When he arrived at the clinic where he was to be treated, at Pasewalk in Pomerania, the doctors recorded it as ‘Gasvergiftung’ l[eicht] Verwundet-Gasvergiftung (lightly wounded, gas poisoning) a description repeated on the 16th Regiment’s casualty list and on numerous other contemporary documents.

Westenkirchner’s Second Version

In a 1934 interview, with the pro-Nazi journalist Heinz A. Heinz, Westenkirchner, gave a slightly, but importantly, different version of events.

‘We were in the neighbourhood of Commines; dazed and bewildered with the ceaseless flash and thunder of explosives…On the night of October 13th-14th the crashing and howling and roaring of the guns was (sic) accompanied by something still more deadly than usual.

Our Company lay on a little hill near Werwick, (sic) a bit to the south of Ypres. All of a sudden, the bombardment slackened off and in place of shells came a queer pungent smell.

Word flew through the trenches that the English were attacking with chlorine gas. Hitherto [we] hadn’t experienced this sort of gas, but now we got a thorough dose of it.

About seven next morning Hitler was dispatched with an order to our rear. Dropping with exhaustion, he staggered off…His eyes were burning, sore, and smarting – gas – he supposed, or dog weariness. Anyhow, they rapidly got worse. The pain was hideous; presently he could see nothing but a fog.

Stumbling, and falling over and over again, he made what feeble progress he could…The last time, all his failing strength was exhausted in freeing himself from the mask…he could struggle up no more…his eyes were searing coals…Hitler collapsed. Goodness only knows how long it was before the stretcher bearers found him. They brought him in, though, at last, and took him to the dressing-station. This was on the morning of October 14th (sic) 1918 – just before the end. Two days later Hitler arrived in hospital at Pasewalk, Pomerania.’

One Event – Three Versions

In the account given to Heinz A. Heinz, Westenkirchner is mistaken both about the date of the gassing (night of October 13th -14th) and the time (two days) taken to travel between Flanders and Pasewalk. Hitler actually had to travel for five days, reaching Pasewalk on the 21st October.

The more important question is whether he was correct in identifying the gas used as chorine rather than Yellow-Cross.

This is crucial because, when it comes to determining the true cause of Hitler’s blindness the gas involved is of the utmost significance.

Had Hitler been exposed to mustard gas, there could well have been physical damage to his eyes that would have required several weeks of hospital treatment.

An analysis of three hundred patients, with moderately severe sight loss due to mustard gas, British doctors found that 72 per cent had regained their sight at the end of a month.

Which means that the interval of approximately one month, between the British attack on October 15th and Hitler’s complete recovery by November 19th, is more or less what would be expected in such a case.

If, however, Hitler had been blinded by some other type of gas then, depending on the extent of his exposure, the effects might have been expected to disappear within either a few hours at best and a few days at worst.

Gas Exposure Was Slight

What seems clear, is that Hitler’s exposure to the gas was brief and injuries to his eyes minimal. According to historian Thomas Weber: ‘The quantity of gas was so small that it would not even had necessitated an extended stay in an army-hospital.’

That was certainly the conclusion of the doctors who examined him at the Oudenaarde hospital, following his transfer from the Front-Line aid station.

Hitler’s medical chit from the Oudenaarde doctors on 16th October, 1918. It gives the diagnosis as gasvergiftet’ (gas poisoned).

Hitler’s medical chit from the Pasewalk ‘nerve clinic’. Noting his admission, on the 21 October 1918, it confirms the original diagnosis and notes he was discharged on the 19 November

After twenty-four hours observation, they made their diagnosis and sent him for treatment.

Not, he must have been bewildered to discover, with the rest of his gassed comrades to the Army’s well-equipped hospital in Brussels, but to a remote Lazarette (clinic) in the town of Pasewalk, six hundred miles away.

The Diagnosis was Hysterical Blindness

The reason for their decision, and for Hitler’s long journey from the Western front to the far North of Germany, was simple.

Under Prussian military law, doctors were prohibited from treating mentally and physically injured soldiers on the same ward, or even in the same hospital. Authorities feared that to allow, what they termed, ‘hysterical’ patients to lie next to those wounded by shot and shell, would be bad for morale.

That it would, like a virus, spread throughout the entire hospital. Infecting the mentally sound and discouraging them from returning to the battle front.

The Pasewalk ‘Nerve Clinic’

The Oudenaarde doctors gave Hitler no explanation for why he was being separated from the soldiers he had fought alongside for four years. Nor was he told the clinic’s true purpose.

It was not a hospital where doctors healed broken bodies but a mental hospital where neurologists and psychiatrists sought to mend shattered minds.

The Hitler’s blindness had been diagnosed as due, not to physical damage to his eyes, but to mental breakdown.

What, in those days, they called ‘hysteria’ and what present day psychiatrists would attribute to Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD).

A Secret of the Nazi State

While PTSD was, and is, nothing to be ashamed. And while the pain and suffering it produced is no less distressing and debilitating than a physical wound, any form of mental illness as then, and still is today, not something a politician would ever wish to disclose.

Once Hitler achieve political prominence, it became essential for the future of his leadership and of the Nazi Party, that he be seen as a man of almost superhuman mental and physical stress.

A Führer whose ‘will’ had always, and would always, reigned supreme.

Not as a soldier who had suffered a mental breakdown, become hysterically blind and been treated by psychiatrists in a ‘nerve hospital’.

As a result, the true cause of Hitler’s blindness, and the treatment he had received at Pasewalk became State Secrets.

Secrets the Nazi’s would resort to murder to safeguard.

Yet, as I argue in my book Triumph of the Will? it was his successful treatment, at the hands of Dr Edmund Forster, one of Germany’s most eminent nerve doctors, that convinced Hitler he had been singled out by a divine power to lead Germany back to glory.

In my next blog I shall explain what Forster’s treatment involved and why it led to such unintended and disastrous consequences.

3344 Comments. Leave new

prednisone 10 mg tablet cost: http://prednisone1st.store/# prednisone canada prices

online singles dating sites: lady dating – single woman free

http://cheapestedpills.com/# gnc ed pills

get generic mobic price: buying cheap mobic no prescription – where to buy generic mobic without insurance

amoxicillin 500 mg cost amoxicillin canada price – how to get amoxicillin

Drug information.

order propecia tablets cost of cheap propecia online

п»їMedicament prescribing information.

propecia pills home

how to get mobic without insurance: where buy mobic tablets – how to get cheap mobic for sale

non prescription erection pills: herbal ed treatment – generic ed pills

https://pharmacyreview.best/# canadian drug prices

where can i buy amoxicillin online: https://amoxicillins.com/# amoxicillin pills 500 mg

ed treatment pills: best ed medications – ed medication online

prescription drugs canada buy online canada drug pharmacy

canadian pharmacy reviews canadian pharmacy meds review

drug information and news for professionals and consumers.

amoxicillin 800 mg price purchase amoxicillin online – buy amoxicillin 500mg capsules uk

Get warning information here.

order propecia without prescription cheap propecia online

reputable canadian pharmacy pharmacy com canada

buying ed pills online non prescription ed drugs the best ed pill

amoxicillin online purchase amoxicillin 500 mg tablets – amoxicillin capsules 250mg

canadianpharmacymeds com 77 canadian pharmacy

cheap propecia online buying generic propecia for sale

https://propecia1st.science/# buy propecia online

https://propecia1st.science/# buying propecia online

cost mobic without dr prescription: can i buy generic mobic without rx – can i buy generic mobic

order generic propecia without dr prescription cost of cheap propecia without a prescription

What side effects can this medication cause?

the canadian drugstore canadian pharmacy online store

Read here.

buying generic propecia pills order generic propecia without rx

https://certifiedcanadapharm.store/# certified canadian international pharmacy

http://mexpharmacy.sbs/# medication from mexico pharmacy

top online pharmacy india: Online medicine order – indian pharmacies safe

mexican rx online: mexican mail order pharmacies – medicine in mexico pharmacies

indian pharmacies safe top 10 pharmacies in india or online shopping pharmacy india

http://solocultivo.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=indiamedicine.world buy medicines online in india

canadian pharmacy india world pharmacy india and indian pharmacy cheapest online pharmacy india

canada drug pharmacy best rated canadian pharmacy or canadian pharmacy drugs online

http://itix.pro/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=certifiedcanadapharm.store buying from canadian pharmacies

trusted canadian pharmacy canadianpharmacymeds and canadian drugs online ed meds online canada

world pharmacy india п»їlegitimate online pharmacies india or pharmacy website india

http://woodsidekitchen.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=indiamedicine.world india online pharmacy

top online pharmacy india Online medicine order and pharmacy website india indian pharmacy online

http://mexpharmacy.sbs/# mexican pharmaceuticals online

canadapharmacyonline legit: the canadian drugstore – canadian pharmacy world reviews

http://indiamedicine.world/# п»їlegitimate online pharmacies india

best online canadian pharmacy: best canadian pharmacy online – canadianpharmacy com

mexican drugstore online mexican mail order pharmacies or mexican pharmaceuticals online

http://halfmoone.org/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=mexpharmacy.sbs mexico pharmacies prescription drugs

mexican online pharmacies prescription drugs п»їbest mexican online pharmacies and п»їbest mexican online pharmacies mexican rx online

http://mexpharmacy.sbs/# buying from online mexican pharmacy

top 10 pharmacies in india: indian pharmacies safe – world pharmacy india

п»їbest mexican online pharmacies: medicine in mexico pharmacies – medicine in mexico pharmacies

indian pharmacy indian pharmacy or indian pharmacy online

https://maps.google.cz/url?q=https://indiamedicine.world best online pharmacy india

pharmacy website india indian pharmacy and reputable indian online pharmacy online shopping pharmacy india

https://indiamedicine.world/# indian pharmacies safe

https://certifiedcanadapharm.store/# canadian pharmacy service

canada rx pharmacy canadian pharmacy ltd or 77 canadian pharmacy

http://tradeext.biz/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=certifiedcanadapharm.store canadian pharmacy online ship to usa

my canadian pharmacy reviews canada pharmacy world and cross border pharmacy canada canadian pharmacy uk delivery

world pharmacy india: п»їlegitimate online pharmacies india – cheapest online pharmacy india

mexican rx online buying prescription drugs in mexico online or buying prescription drugs in mexico online

http://www.forfrontmedicine.net/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=mexpharmacy.sbs best online pharmacies in mexico

mexico pharmacies prescription drugs best online pharmacies in mexico and reputable mexican pharmacies online best online pharmacies in mexico

canadian pharmacy world reviews: trusted canadian pharmacy – canadian online pharmacy

https://indiamedicine.world/# india online pharmacy

canada online pharmacy: canadian pharmacy 1 internet online drugstore – online canadian drugstore

reputable indian pharmacies india pharmacy or best online pharmacy india

http://alexandrahumphrey.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=indiamedicine.world reputable indian online pharmacy

pharmacy website india cheapest online pharmacy india and mail order pharmacy india buy prescription drugs from india

http://mexpharmacy.sbs/# п»їbest mexican online pharmacies

canadian pharmacy online: best canadian online pharmacy – pet meds without vet prescription canada

https://indiamedicine.world/# top online pharmacy india

online canadian pharmacy review: canada drugs reviews – legit canadian pharmacy

precription drugs from canada canadian drug pharmacy or canadian pharmacy no rx needed

http://ccbcommunitybank.net/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=certifiedcanadapharm.store canada rx pharmacy

online canadian pharmacy canadian pharmacy ratings and precription drugs from canada rate canadian pharmacies

buying from online mexican pharmacy best online pharmacies in mexico or buying from online mexican pharmacy

http://danhyatt.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=mexpharmacy.sbs mexican online pharmacies prescription drugs

mexican drugstore online mexican drugstore online and mexican rx online mexico drug stores pharmacies

top 10 online pharmacy in india reputable indian online pharmacy or mail order pharmacy india

http://batteryparkcitycommunitycenter.org/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=indiamedicine.world top online pharmacy india

reputable indian online pharmacy indian pharmacy and mail order pharmacy india Online medicine order

mexico drug stores pharmacies: purple pharmacy mexico price list – reputable mexican pharmacies online

http://mexpharmacy.sbs/# medication from mexico pharmacy

zithromax price south africa zithromax price canada zithromax 500 mg for sale

https://stromectolonline.pro/# ivermectin pill cost

https://azithromycin.men/# zithromax for sale 500 mg

medicine neurontin buy neurontin 100 mg canada or drug neurontin 20 mg

http://hudsonappraisal.org/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=gabapentin.pro neurontin 200

price of neurontin neurontin 800 mg price and neurontin 600 mg pill neurontin 800 mg tablets best price

zithromax 250 price: zithromax – how to buy zithromax online

buy zithromax 1000 mg online zithromax 500 tablet or where can i buy zithromax uk

http://creditmycar.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=azithromycin.men buy cheap zithromax online

zithromax cost australia where to get zithromax and zithromax 500 mg lowest price online purchase zithromax z-pak

neurontin brand name 800mg neurontin gabapentin neurontin 3

neurontin generic brand: neurontin price india – neurontin 800 mg pill

buy liquid ivermectin purchase ivermectin or cost of ivermectin lotion

http://rankgrp.biz/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=stromectolonline.pro ivermectin 1% cream generic

ivermectin drug ivermectin lotion for lice and ivermectin 5 mg price ivermectin canada

https://stromectolonline.pro/# ivermectin buy online

https://azithromycin.men/# generic zithromax over the counter

neurontin 100 mg cap order neurontin or purchase neurontin online

http://happycaldwell.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=gabapentin.pro purchase neurontin canada

neurontin price south africa neurontin from canada and buy neurontin buy cheap neurontin

buy neurontin online no prescription neurontin brand name or purchase neurontin

http://hepatocult.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=gabapentin.pro medicine neurontin

[url=http://stores.shopforge.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=gabapentin.pro]neurontin oral[/url] buying neurontin online and [url=https://tc.yuedotech.com/home.php?mod=space&uid=222527]neurontin 800 mg tablet[/url] prescription drug neurontin

ivermectin 6 mg tablets: ivermectin australia – ivermectin 1 cream generic

https://gabapentin.pro/# buy gabapentin

https://azithromycin.men/# zithromax 250 mg australia

https://ed-pills.men/# ed medication online

http://ed-pills.men/# erection pills viagra online

top erection pills: cheapest ed pills online – cheap erectile dysfunction pills online

cheapest antibiotics buy antibiotics or buy antibiotics from canada

http://mariposaculturalfoundation.org/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=antibiotic.guru buy antibiotics online

get antibiotics quickly buy antibiotics from canada and antibiotic without presription antibiotic without presription

ed medication online: how to cure ed – generic ed pills

paxlovid cost without insurance paxlovid buy or paxlovid for sale

http://www.60smovies.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=paxlovid.top Paxlovid buy online

paxlovid for sale paxlovid covid and buy paxlovid online paxlovid price

compare ed drugs ed meds online or п»їerectile dysfunction medication

http://morochata.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=ed-pills.men ed meds online without doctor prescription

best treatment for ed ed pills comparison and erectile dysfunction drugs new ed pills

http://lipitor.pro/# lipitor 10

buy cytotec in usa: cytotec online – п»їcytotec pills online

https://misoprostol.guru/# buy cytotec online fast delivery

buy cytotec in usa buy cytotec in usa buy misoprostol over the counter

https://avodart.pro/# can i order avodart no prescription

http://misoprostol.guru/# purchase cytotec

purchase cytotec order cytotec online buy cytotec

Misoprostol 200 mg buy online buy cytotec pills or Abortion pills online

http://misiga.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=misoprostol.guru cytotec abortion pill

buy cytotec over the counter Misoprostol 200 mg buy online and order cytotec online buy cytotec pills online cheap

http://misoprostol.guru/# Abortion pills online

https://misoprostol.guru/# purchase cytotec

pfizer lipitor: buying lipitor from canada – buy generic lipitor

https://avodart.pro/# get generic avodart prices

lipitor 10mg price australia lipitor generic brand name lipitor 20mg canada price

http://lisinopril.pro/# lisinopril 2.5 cost

where to buy generic avodart prices can i order generic avodart without a prescription how to get cheap avodart without rx

http://avodart.pro/# can i order avodart for sale

lipitor 20mg price australia lipitor generic brand or lipitor purchase online

http://ketmayo.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=lipitor.pro cost of lipitor

lipitor generic drug lipitor tabs and lipitor 40 mg cost lipitor price uk

buy cipro online without prescription buy cipro without rx or buy cipro online

http://greendonkey.org/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=ciprofloxacin.ink cipro online no prescription in the usa

cipro ciprofloxacin cipro online no prescription in the usa and where to buy cipro online ciprofloxacin order online

can you buy generic avodart without a prescription can i purchase avodart prices or can you get generic avodart online

http://telesleep.net/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=avodart.pro where can i get generic avodart tablets

where to buy generic avodart pills can i get avodart without insurance and how can i get avodart without insurance how can i get avodart tablets

https://lisinopril.pro/# lisinopril 40 mg canada

lipitor prescription drug: lipitor over the counter – lipitor prices compare

http://avodart.pro/# order avodart

buy cytotec pills buy cytotec Misoprostol 200 mg buy online

buy cytotec in usa buy misoprostol over the counter or buy cytotec over the counter

http://schipper.us/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=misoprostol.guru Abortion pills online

buy cytotec cytotec pills buy online and buy cytotec online fast delivery Misoprostol 200 mg buy online

http://lisinopril.pro/# generic for prinivil

https://lisinopril.pro/# lisinopril 5mg buy

buy ciprofloxacin over the counter ciprofloxacin over the counter buy generic ciprofloxacin

http://avodart.pro/# where to get cheap avodart without dr prescription

https://misoprostol.guru/# buy cytotec pills

cheap lipitor lipitor without prescription or price of lipitor 40 mg

http://bonnermenking.net/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=lipitor.pro how much is lipitor

lipitor 10mg tablets where to buy lipitor and lipitor online pharmacy lipitor brand name

cheap avodart pill where buy generic avodart without a prescription or can you get generic avodart without prescription

http://dangelica.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=avodart.pro can you buy cheap avodart without insurance

can you get avodart without dr prescription where buy cheap avodart without insurance and how to get cheap avodart without insurance where can i buy generic avodart for sale

http://avodart.pro/# how to buy cheap avodart without dr prescription

purchase cytotec cytotec online buy cytotec online

http://lipitor.pro/# cheap lipitor

buying prescription drugs in mexico online: mexican drugstore online – medicine in mexico pharmacies

online canadian drugstore canadian pharmacy antibiotics or canadian pharmacy 24h com

http://nellysetc.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=certifiedcanadapills.pro best canadian online pharmacy

safe online pharmacies in canada legitimate canadian mail order pharmacy and canadadrugpharmacy com trusted canadian pharmacy

canadian pharmacy near me canadian drugs pharmacy or canadian discount pharmacy

http://www.youblog.cc/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=certifiedcanadapills.pro legal canadian pharmacy online

my canadian pharmacy rx canadian pharmacy ltd and cheapest pharmacy canada canada online pharmacy

п»їlegitimate online pharmacies india Online medicine order or cheapest online pharmacy india

http://www.kemperarenakc.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=indiapharmacy.cheap best india pharmacy

indianpharmacy com online shopping pharmacy india and india pharmacy mail order indian pharmacies safe

http://mexicanpharmacy.guru/# mexico pharmacies prescription drugs

Kamagra tablets Kamagra Oral Jelly buy online or Kamagra tablets

http://marketing-depot.net/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=kamagra.men order kamagra oral jelly

kamagra Kamagra tablets and order kamagra oral jelly buy kamagra online

cialis with dapoxetine australia overnight delivery canadian cialis for sale or viagra cialis trial pack

http://420realestatefinancing.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=cialis.science can you buy cialis without a prescription

cheapest generic cialis best price for cialis 20 mg and cialis for sell generic cialis uk

natural remedies for ed ed medications list or best medication for ed

http://artbooksinc.net/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=edpill.men ed medications online

ed meds online without doctor prescription how to cure ed and ed medication new ed pills

order kamagra oral jelly kamagra or order kamagra oral jelly

http://rhsf.net/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=kamagra.men kamagra

kamagra kamagra and kamagra oral jelly kamagra

how much is ivermectin cost of stromectol medication or generic ivermectin cream

http://nbcbug.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=ivermectin.today ivermectin ebay

ivermectin 2ml ivermectin coronavirus and ivermectin 3 buy ivermectin nz

stromectol 3 mg price where to buy stromectol online or stromectol in canada

http://californiaclub.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=ivermectin.today ivermectin 2mg

ivermectin cost canada ivermectin eye drops and ivermectin 1 cream generic ivermectin cream

stromectol tablet 3 mg ivermectin cream 1% or ivermectin lice

http://rubystandards.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=ivermectin.auction ivermectin 400 mg brands

stromectol 3 mg tablet buy stromectol uk and ivermectin pills human ivermectin 3 mg tablet dosage

ivermectin 8000 ivermectin 8 mg or ivermectin 1mg

http://ronaldo.us/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=ivermectin.today stromectol covid 19

stromectol 3 mg tablet stromectol 3mg tablets and ivermectin 1 cream 45gm stromectol 12mg

neurontin 2018 neurontin rx or neurontin cap 300mg price

http://attackbunnies.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=gabamed.store neurontin 800 pill

neurontin 300 mg price gabapentin 600 mg and neurontin price india neurontin 300 mg tablets

ivermectin stromectol ivermectin 3mg tablets or order stromectol

http://www.freecellphonelookups.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=ivermectinpharmacy.best buy ivermectin nz

stromectol prices where to buy ivermectin and ivermectin iv stromectol cream

furosemida furosemide 40 mg or lasix 100 mg tablet

http://vpospayment.us/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=lasixfurosemide.store lasix generic name

lasix uses lasix 100 mg and lasix 20 mg furosemide 100 mg

legitimate canadian pharmacy canadian pharmacy checker or ed drugs online from canada

http://discounthotelshomepage.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=canadaph.pro certified canadian pharmacy

canadian pharmacy no scripts best canadian online pharmacy and canada cloud pharmacy buy canadian drugs

canada online pharmacy: canadian pharmacy online – canadian pharmacy

online shopping pharmacy india top 10 online pharmacy in india or indian pharmacy online

http://vaqueroenergyinc.info/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=indiaph.ink indian pharmacy paypal

buy prescription drugs from india online pharmacy india and best online pharmacy india top 10 online pharmacy in india

canadian pharmacy service canadian king pharmacy or safe canadian pharmacy

http://www.opsexchange.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=canadaph.pro canadian family pharmacy

the canadian pharmacy canada pharmacy reviews and canadian pharmacies online 77 canadian pharmacy

mexico pharmacies prescription drugs mexican rx online or mexican border pharmacies shipping to usa

http://aaronbroder.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=mexicoph.icu mexico drug stores pharmacies

buying prescription drugs in mexico pharmacies in mexico that ship to usa and mexican drugstore online mexican rx online

1″‘`–

1

canadian king pharmacy: onlinecanadianpharmacy – canadianpharmacymeds

online drugs without prescription buy medications online no prescription certified canadian international pharmacy

canada meds com no rx meds or buy medications online without prescription

http://badboysofgiveback.org/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=interpharm.pro canadian pharmacy services

buy drugs online without a prescription top canadian online pharmacy and online pharmacy no presc medicine with no prescription

cheap canadian pharmacy is canada drugs online safe or how to stop calls from canadian online pharmacy

http://www.startupfutures.net/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=internationalpharmacy.icu best canadian mail order pharmacy

canadian pharma canadian pharmacy online and canadian pharmacy no prescription required order from canadian pharmacy

what is the best online pharmacy best online pharmacy without prescription or buy medication online with prescription

http://afterwork.info/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=internationalpharmacy.icu mail order canadian pharmacy

online-rx what is the best mail order pharmacy and online pharmacies without prescriptions pharmacies online canada

canadaian pharmacy canadian-pharmacy or order prescription from canada

https://docs.whirlpool.eu/?brand=bk&locale=de&linkreg=https://internationalpharmacy.icu canada rx prices

[url=http://rykocarwash.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=internationalpharmacy.icu]rx mexico online[/url] pharmacies without prescriptions and [url=http://talk.dofun.cc/home.php?mod=space&uid=5673]pharmacies online canada[/url] online canadian pharmacy

best website to buy prescription drugs online medicine without prescription or canada meds online

http://hoboenergypro.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=internationalpharmacy.icu canadian pharamacy

buy prescription online canadian prescription drugstore reviews and canadian oharmacy mexican farmacia online

best online mexican pharmacy online canadian pharmacy no prescription or us based online pharmacy

http://digiroad.info/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=interpharm.pro order prescription from canada

no prescription on line pharmacies canada world pharmacy and online canadian pharmacy no prescription canada prescription

farmaci senza ricetta elenco farmacia online senza ricetta farmacia online migliore

Pharmacie en ligne livraison rapide acheter mГ©dicaments Г l’Г©tranger or Pharmacie en ligne livraison 24h

http://peraceticacidsuppliers.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=pharmacieenligne.icu Pharmacie en ligne France

Pharmacie en ligne fiable Acheter mГ©dicaments sans ordonnance sur internet and pharmacie ouverte pharmacie ouverte 24/24

comprare farmaci online all’estero п»їfarmacia online migliore or farmacia online miglior prezzo

http://popcornomicon.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=farmaciaonline.men farmacia online

farmacie online sicure farmacia online migliore and farmacia online senza ricetta farmacie online autorizzate elenco

https://pharmacieenligne.icu/# Pharmacie en ligne livraison 24h

farmacia envГos internacionales farmacia barata or farmacia online madrid

http://colchestercnc.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=farmaciabarata.pro farmacia 24h

farmacia barata farmacia envГos internacionales and farmacia 24h farmacias online seguras en espaГ±a

http://pharmacieenligne.icu/# Pharmacie en ligne livraison rapide

п»їpharmacie en ligne Acheter mГ©dicaments sans ordonnance sur internet or Pharmacies en ligne certifiГ©es

http://www.elaisha.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=pharmacieenligne.icu Pharmacies en ligne certifiГ©es

Pharmacie en ligne livraison rapide Acheter mГ©dicaments sans ordonnance sur internet and Pharmacie en ligne sans ordonnance Acheter mГ©dicaments sans ordonnance sur internet

versandapotheke deutschland internet apotheke or online apotheke deutschland

http://aquachannel.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=edapotheke.store versandapotheke

versandapotheke internet apotheke and online apotheke preisvergleich online apotheke deutschland

Viagra sans ordonnance 24h

http://edpharmacie.pro/# acheter mГ©dicaments Г l’Г©tranger

comprare farmaci online con ricetta farmacie on line spedizione gratuita or farmaci senza ricetta elenco

http://albertapga.info/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=itfarmacia.pro farmacie online autorizzate elenco

farmacia online migliori farmacie online 2023 and comprare farmaci online con ricetta comprare farmaci online con ricetta

Viagra sans ordonnance 24h

http://itfarmacia.pro/# farmacia online migliore

farmacia 24h farmacias baratas online envГo gratis or farmacia envГos internacionales

http://www.budschickenandseafood.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=esfarmacia.men farmacia online 24 horas

farmacia online internacional farmacia envГos internacionales and farmacia 24h farmacia envГos internacionales

Pharmacie en ligne pas cher pharmacie ouverte 24/24 or Pharmacie en ligne pas cher

http://intercomponline.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=edpharmacie.pro Pharmacie en ligne livraison rapide

п»їpharmacie en ligne Pharmacie en ligne pas cher and pharmacie ouverte 24/24 Pharmacie en ligne sans ordonnance

acheter sildenafil 100mg sans ordonnance

medication from mexico pharmacy: medicine in mexico pharmacies – medication from mexico pharmacy

best canadian pharmacy to buy from safe canadian pharmacies or canada pharmacy world

http://zen5footwear.net/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=canadapharm.store canadian pharmacy com

canada drugs online review cheapest pharmacy canada and best canadian online pharmacy canadian pharmacy 1 internet online drugstore

drugs from canada canadian pharmacy review or best canadian online pharmacy

http://www.homir.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=canadapharm.store canadian pharmacy ltd

canadian pharmacy ltd canadianpharmacy com and canada drugs reviews ed drugs online from canada

Efficient, reliable, and internationally acclaimed. top 10 online pharmacy in india: indian pharmacy online – india pharmacy

top 10 pharmacies in india india pharmacy mail order or Online medicine order

http://montagevillascondos.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=indiapharm.cheap top 10 pharmacies in india

top online pharmacy india indian pharmacy paypal and top online pharmacy india mail order pharmacy india

77 canadian pharmacy: canadian pharmacy scam – www canadianonlinepharmacy

buy medicines online in india: online shopping pharmacy india – online shopping pharmacy india

buying prescription drugs in mexico medicine in mexico pharmacies or mexico pharmacies prescription drugs

http://borrowerrequests.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=mexicopharm.store mexican online pharmacies prescription drugs

pharmacies in mexico that ship to usa buying prescription drugs in mexico online and mexican mail order pharmacies pharmacies in mexico that ship to usa

They provide access to global brands that are hard to find locally. mexico drug stores pharmacies: mexican online pharmacies prescription drugs – buying from online mexican pharmacy

cheap canadian pharmacy online canadian pharmacy king reviews or canadapharmacyonline

http://tricksuppressors.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=canadapharm.store pharmacy rx world canada

best rated canadian pharmacy canada pharmacy online and online canadian pharmacy canada drugs online reviews

medication from mexico pharmacy: best online pharmacies in mexico – mexican border pharmacies shipping to usa

Their patient care is unparalleled. buying prescription drugs in mexico online: mexican border pharmacies shipping to usa – mexico drug stores pharmacies

medicine in mexico pharmacies: best online pharmacies in mexico – reputable mexican pharmacies online

canadianpharmacymeds canada pharmacy reviews or best online canadian pharmacy

http://churchalmanac.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=canadapharm.store www canadianonlinepharmacy

legit canadian pharmacy global pharmacy canada and best canadian pharmacy online pharmacy com canada

best ed treatment pills impotence pills erectile dysfunction pills

22 doxycycline doxycycline 500mg or doxycycline hyc 100 mg

http://meandmyfinances.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=doxycyclineotc.store doxycycline 100mg cost uk

doxycycline capsules for sale doxycycline capsules 50mg 100mg and purchase doxycycline 100mg doxycycline for sale uk

https://doxycyclineotc.store/# no prescription doxycycline

Trustworthy and efficient with every international delivery. http://azithromycinotc.store/# can you buy zithromax over the counter in australia

A pharmacy that prioritizes global health. https://azithromycinotc.store/# zithromax generic price

ed medications how to cure ed or cheap erectile dysfunction

http://smarttuitionvsfacts.net/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=edpillsotc.store online ed pills

ed drugs list top ed drugs and drugs for ed best ed pills online

where can you buy zithromax zithromax generic cost or zithromax buy online

http://meetingsourcebook.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=azithromycinotc.store zithromax 250 mg tablet price

buy zithromax 500mg online zithromax and zithromax online where to buy zithromax in canada

doxycycline pills cost buy doxycycline for acne doxycycline cheap uk

Hassle-free prescription transfers every time. https://drugsotc.pro/# discount pharmacy

best online pharmacy no prescription canadian mail order pharmacy no prescription needed canadian pharmacy

reputable indian online pharmacy reputable indian online pharmacy or indian pharmacy paypal

http://richmap.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=indianpharmacy.life п»їlegitimate online pharmacies india

п»їlegitimate online pharmacies india reputable indian pharmacies and pharmacy website india Online medicine order

Their global perspective enriches local patient care. http://indianpharmacy.life/# indianpharmacy com

They offer unparalleled advice on international healthcare. http://indianpharmacy.life/# top 10 online pharmacy in india

online pharmacy europe pharmacy canadian superstore or canadian neighbor pharmacy

http://countryoakflooring.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=drugsotc.pro safe reliable canadian pharmacy

pharmacy in canada for viagra canadian online pharmacy reviews and rx online pharmacy п»їcanadian pharmacy online

Their commitment to healthcare excellence is evident. http://drugsotc.pro/# cialis online pharmacy

pharmacy website india india pharmacy or indian pharmacies safe

http://rgbstore.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=indianpharmacy.life india pharmacy

cheapest online pharmacy india indian pharmacy online and Online medicine order buy medicines online in india

mexico drug stores pharmacies best online pharmacy in Mexico mexico drug stores pharmacies

Professional, courteous, and attentive – every time. https://indianpharmacy.life/# indian pharmacy online

silkroad online pharmacy cheapest pharmacy canada or canadian pharmacy drugs online

http://asi-ipsos.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=drugsotc.pro international online pharmacy

canada pharmacy not requiring prescription canadian pharmacy online ship to usa and online canadian pharmacy coupon indian trail pharmacy

mexican pharmaceuticals online buying prescription drugs in mexico or best online pharmacies in mexico

http://zap-pads.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=mexicanpharmacy.site mexican pharmaceuticals online

mexico drug stores pharmacies mexico drug stores pharmacies and mexican rx online buying prescription drugs in mexico online

They have a great selection of wellness products. http://drugsotc.pro/# canadian pharmacy 24h com safe

online pharmacy dubai northern pharmacy or www canadianonlinepharmacy

http://cenegenicscis.net/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=drugsotc.pro canadian pharmacy king

legitimate canadian pharmacy online legitimate canadian pharmacies and order pharmacy online egypt prices pharmacy

mexico drug stores pharmacies order pills online from a mexican pharmacy mexican drugstore online

trustworthy canadian pharmacy online pharmacy cialis or canadian discount pharmacy

http://ww17.watchino.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=drugsotc.pro modafinil online pharmacy

top mail order pharmacies canadian pharmacy levitra and canadian pharmacy mall best online thai pharmacy

Their international collaborations benefit patients immensely. https://mexicanpharmacy.site/# mexican online pharmacies prescription drugs

reputable indian pharmacies reputable indian online pharmacy or reputable indian pharmacies

http://fsr.shineforchrist.org/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=indianpharmacy.life indianpharmacy com

reputable indian pharmacies buy medicines online in india and best online pharmacy india buy medicines online in india

Their vaccination services are quick and easy. https://drugsotc.pro/# online pharmacy com

canada pharmacy online: cheap drugs from canada – northern pharmacy canada

I’ve sourced rare medications thanks to their global network. https://canadapharmacy.cheap/# canadian discount pharmacy

canada meds online: canada pharmacy store – online doctor prescription canada

canada drugs online reviews buy drugs from canada or canadian pharmacy king

http://esperanzavillarentals.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=canadapharmacy.cheap canadian pharmacy world

best canadian pharmacy online canadapharmacyonline legit and ed meds online canada canada drug pharmacy

best online canadian pharmacy reviews online canadian pharmacy or candian pharmacy

http://reinsurex.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=internationalpharmacy.pro no script pharmacy

canadiam pharmacy buy prescription drugs online without doctor and canadian pharmacy mail order best online pharmacies without prescription

canadian online pharmacy best rated canadian pharmacy or canada drug pharmacy

http://verhelleny.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=canadapharmacy.cheap canadian pharmacy king

canadian medications canadian compounding pharmacy and canada discount pharmacy best canadian pharmacy online

mexico drug stores pharmacies and mail order pharmacy mexico – mexican border pharmacies shipping to usa

medicine in mexico pharmacies – mexican pharmacy online – purple pharmacy mexico price list

Their commitment to global excellence is unwavering. https://mexicanpharmonline.com/# mexico drug stores pharmacies

medication from mexico pharmacy mexican pharmacy online mexican drugstore online

pharmacies in mexico that ship to usa and mexico pharmacy price list – mexican online pharmacies prescription drugs

reputable mexican pharmacies online or mexican pharmacy online – mexican drugstore online

Top 100 Searched Drugs. http://mexicanpharmonline.com/# mexico pharmacies prescription drugs

п»їbest mexican online pharmacies mexican pharmacies mexican drugstore online

reputable mexican pharmacies online mexico pharmacies prescription drugs or mexico pharmacies prescription drugs

http://iowa80chrome.mobi/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=mexicanpharmonline.shop mexico drug stores pharmacies

mexican rx online best online pharmacies in mexico and mexico pharmacies prescription drugs mexico drug stores pharmacies

reputable mexican pharmacies online and mexico pharmacy price list – mexican pharmaceuticals online

earch our drug database. http://mexicanpharmonline.shop/# mexican pharmaceuticals online

best online pharmacies in mexico mexican pharmacy online buying prescription drugs in mexico

п»їlegitimate online pharmacies india: canadian pharmacy india – buy medicines online in india

https://stromectol24.pro/# minocycline hydrochloride

legal canadian pharmacy online: canada pharmacy – vipps approved canadian online pharmacy

canada drugstore pharmacy rx vipps canadian pharmacy or legit canadian pharmacy online

http://goldminemadeeasy.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=canadapharmacy24.pro canadian pharmacies

legitimate canadian mail order pharmacy best canadian online pharmacy reviews and northwest canadian pharmacy trustworthy canadian pharmacy

stromectol ivermectin tablets minocycline pills or ivermectin 3mg tablet

http://ambroselawfirm.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=stromectol24.pro ivermectin 1

stromectol for head lice cost of ivermectin 1% cream and buy minocycline 100mg stromectol without prescription

http://canadapharmacy24.pro/# canadian compounding pharmacy

buy prescription drugs from india top 10 pharmacies in india or india pharmacy

http://lucrepelaweb.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=indiapharmacy24.pro mail order pharmacy india

indian pharmacy top 10 online pharmacy in india and pharmacy website india india pharmacy mail order

legit canadian pharmacy: canadian pharmacy pro – safe canadian pharmacy

minocycline for acne 100mg: stromectol tablets buy online – ivermectin lice

buy ivermectin stromectol covid or stromectol xr

http://worldloveday.org/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=stromectol24.pro stromectol 3 mg price

stromectol for sale ivermectin usa price and stromectol liquid minocycline 100 mg for sale

canadian family pharmacy online canadian drugstore or canada pharmacy

http://www.restlessnurse.net/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=canadapharmacy24.pro medication canadian pharmacy

safe reliable canadian pharmacy best rated canadian pharmacy and canada rx pharmacy canadian drugstore online

https://indiapharmacy24.pro/# reputable indian pharmacies

http://plavix.guru/# buy clopidogrel bisulfate

valtrex prices: buy antiviral drug – how much is valtrex in canada

http://paxlovid.bid/# paxlovid pill

stromectol coronavirus stromectol 6 mg tablet minocycline 100 mg online

cost for valtrex generic valtrex cost or price of valtrex in canada

http://surfoxsystem.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=valtrex.auction how much is valtrex

valtrex cost in mexico valtrex medicine purchase and discount valtrex online buy generic valtrex without prescription

https://plavix.guru/# generic plavix

plavix medication: buy Clopidogrel over the counter – generic plavix

Paxlovid buy online: buy paxlovid online – paxlovid pill

https://valtrex.auction/# valtrex prices canada

can i purchase cheap mobic without prescription buy anti-inflammatory drug can i order mobic price

buy Clopidogrel over the counter Clopidogrel 75 MG price or Plavix generic price

http://overturecenterfoundation.net/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=plavix.guru buy clopidogrel bisulfate

generic plavix Plavix 75 mg price and buy Clopidogrel over the counter Clopidogrel 75 MG price

paxlovid for sale paxlovid india or paxlovid india

http://everygirl.info/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=paxlovid.bid paxlovid covid

paxlovid cost without insurance paxlovid for sale and buy paxlovid online paxlovid cost without insurance

buy clopidogrel bisulfate: antiplatelet drug – п»їplavix generic

http://plavix.guru/# п»їplavix generic

ivermectin medication ivermectin 50ml or minocycline 50 mg tablets for humans for sale

http://nissan-stanfield.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=stromectol.icu stromectol tab

ivermectin price uk order stromectol online and ivermectin 9mg minocycline 100 mg

plavix medication: clopidogrel bisulfate 75 mg – Cost of Plavix without insurance

http://valtrex.auction/# buy valtrex online prescription

Plavix 75 mg price Plavix generic price clopidogrel bisulfate 75 mg

valtrex tablets price canadian valtrex no rx or valtrex over the counter australia

http://hvn.lettersfromthecosmos.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=valtrex.auction valtrex price without insurance

valtrex price south africa valtrex online no prescription and buy valtrex online valtrex without insurance

can you get cheap mobic without prescription: Mobic meloxicam best price – get mobic

https://plavix.guru/# plavix best price

paxlovid cost without insurance paxlovid pill or paxlovid price

http://juleslennonphotography.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=paxlovid.bid paxlovid generic

paxlovid covid paxlovid price and paxlovid cost without insurance paxlovid for sale

generic sildenafil [url=https://viagra.eus/#]Cheap Viagra 100mg[/url] sildenafil over the counter

http://kamagra.icu/# Kamagra tablets

Buy Vardenafil online Levitra generic best price Vardenafil buy online

https://cialis.foundation/# Tadalafil price

https://cialis.foundation/# Generic Cialis price

п»їkamagra super kamagra or Kamagra 100mg

http://laelzapata.net/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=kamagra.icu п»їkamagra

super kamagra super kamagra and super kamagra super kamagra

https://kamagra.icu/# Kamagra Oral Jelly

Tadalafil Tablet Generic Cialis without a doctor prescription or buy cialis pill

http://jacobungermd.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=cialis.foundation Buy Tadalafil 10mg

Buy Tadalafil 10mg Buy Tadalafil 10mg and cheapest cialis п»їcialis generic

cialis for sale Cialis 20mg price Cialis over the counter

over the counter sildenafil Cheap generic Viagra or order viagra

http://drillbeat.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=viagra.eus Generic Viagra online

Cheap Viagra 100mg Viagra tablet online and cheap viagra Viagra without a doctor prescription Canada

Vardenafil buy online Cheap Levitra online Levitra 10 mg buy online

http://viagra.eus/# Buy Viagra online cheap

cialis for sale cheapest cialis or Generic Tadalafil 20mg price

http://recyclewirelessphones.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=cialis.foundation buy cialis pill

Generic Tadalafil 20mg price cheapest cialis and Tadalafil Tablet Generic Cialis price

https://kamagra.icu/# Kamagra 100mg price

Kamagra 100mg price buy kamagra online usa Kamagra 100mg price

http://kamagra.icu/# buy kamagra online usa

https://levitra.eus/# Buy Vardenafil online

super kamagra Kamagra tablets or Kamagra 100mg

http://www.round5.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=kamagra.icu buy kamagra online usa

Kamagra tablets Kamagra 100mg and Kamagra 100mg price buy kamagra online usa

Viagra generic over the counter Viagra generic over the counter or best price for viagra 100mg

http://www.designstein.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=viagra.eus Viagra online price

Cheap generic Viagra online Viagra Tablet price and Viagra online price Sildenafil Citrate Tablets 100mg

п»їkamagra sildenafil oral jelly 100mg kamagra Kamagra 100mg price

http://viagra.eus/# Cheap generic Viagra online

Generic Cialis without a doctor prescription п»їcialis generic or п»їcialis generic

http://ballistic-medball.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=cialis.foundation Tadalafil price

Tadalafil Tablet Generic Cialis without a doctor prescription and п»їcialis generic cheapest cialis

https://kamagra.icu/# super kamagra

over the counter sildenafil Generic Viagra online Sildenafil Citrate Tablets 100mg

https://viagra.eus/# Viagra without a doctor prescription Canada

http://kamagra.icu/# Kamagra 100mg price

Viagra Tablet price sildenafil over the counter or generic sildenafil

http://hollywoodstock.org/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=viagra.eus cheap viagra

buy viagra here cheapest viagra and generic sildenafil best price for viagra 100mg

sildenafil oral jelly 100mg kamagra Kamagra tablets Kamagra tablets

medication from mexico pharmacy: mexican drugstore online – medicine in mexico pharmacies mexicanpharmacy.company

best online pharmacy india: buy prescription drugs from india – top online pharmacy india indiapharmacy.pro

pharmacies in mexico that ship to usa: reputable mexican pharmacies online – mexico drug stores pharmacies mexicanpharmacy.company

https://canadapharmacy.guru/# best mail order pharmacy canada canadapharmacy.guru

canadadrugpharmacy com: best online canadian pharmacy – medication canadian pharmacy canadapharmacy.guru

mexican drugstore online buying from online mexican pharmacy mexican rx online mexicanpharmacy.company

http://canadapharmacy.guru/# canadian neighbor pharmacy canadapharmacy.guru

world pharmacy india buy prescription drugs from india or india online pharmacy

http://replens.eu/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=indiapharmacy.pro indian pharmacies safe

reputable indian online pharmacy canadian pharmacy india and online shopping pharmacy india india online pharmacy

mexican drugstore online mexico drug stores pharmacies or reputable mexican pharmacies online

http://bestlawyersinsouthcarolina.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=mexicanpharmacy.company mexico drug stores pharmacies

medication from mexico pharmacy mexican online pharmacies prescription drugs and best online pharmacies in mexico mexican border pharmacies shipping to usa

buy medicines online in india: Online medicine order – indian pharmacy paypal indiapharmacy.pro

mexican drugstore online: pharmacies in mexico that ship to usa – buying prescription drugs in mexico online mexicanpharmacy.company

buy prescription drugs from india: buy medicines online in india – indian pharmacy paypal indiapharmacy.pro

canadian pharmacy rate canadian pharmacies canadian pharmacy 24 canadapharmacy.guru

http://indiapharmacy.pro/# best online pharmacy india indiapharmacy.pro

canadian pharmacy king canadian drugs pharmacy or canadian medications

http://vancouverumbrellas.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=canadapharmacy.guru trusted canadian pharmacy

vipps canadian pharmacy reddit canadian pharmacy and canadian pharmacy world legit canadian pharmacy

mail order pharmacy india: п»їlegitimate online pharmacies india – india online pharmacy indiapharmacy.pro

https://canadapharmacy.guru/# best canadian online pharmacy canadapharmacy.guru

best online pharmacy india buy medicines online in india or india online pharmacy

http://sawmilltrust.net/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=indiapharmacy.pro top 10 online pharmacy in india

top online pharmacy india top online pharmacy india and indian pharmacy online india online pharmacy

mexican mail order pharmacies: mexican pharmacy – buying prescription drugs in mexico online mexicanpharmacy.company

canadian discount pharmacy: ordering drugs from canada – safe canadian pharmacy canadapharmacy.guru

reputable indian pharmacies india pharmacy indian pharmacy indiapharmacy.pro

www canadianonlinepharmacy canadian valley pharmacy or trustworthy canadian pharmacy

http://rtdu.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=canadapharmacy.guru trustworthy canadian pharmacy

canada rx pharmacy my canadian pharmacy and real canadian pharmacy reputable canadian online pharmacy

purple pharmacy mexico price list п»їbest mexican online pharmacies or mexican border pharmacies shipping to usa

http://www.floodins.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=mexicanpharmacy.company&popup=1 mexico pharmacies prescription drugs

[url=http://ipneumacult.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=mexicanpharmacy.company]buying prescription drugs in mexico online[/url] mexico drug stores pharmacies and [url=https://forex-bitcoin.com/members/298619-ecudxrqmdi]buying prescription drugs in mexico[/url] medicine in mexico pharmacies

canadian pharmacy tampa: ed drugs online from canada – best canadian pharmacy canadapharmacy.guru

best canadian pharmacy online: canada pharmacy online – global pharmacy canada canadapharmacy.guru

top 10 online pharmacy in india canadian pharmacy india reputable indian pharmacies indiapharmacy.pro

http://indiapharmacy.pro/# cheapest online pharmacy india indiapharmacy.pro

best india pharmacy best online pharmacy india or п»їlegitimate online pharmacies india

http://avnetconsulting.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=indiapharmacy.pro top 10 online pharmacy in india

indian pharmacy paypal cheapest online pharmacy india and buy medicines online in india indian pharmacy online

canadian pharmacy meds reviews best online canadian pharmacy or online canadian pharmacy reviews

http://rent4people.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=canadapharmacy.guru buy prescription drugs from canada cheap

canada rx pharmacy canadian online pharmacy reviews and northwest pharmacy canada legitimate canadian pharmacies

mexico drug stores pharmacies: medication from mexico pharmacy – mexico drug stores pharmacies mexicanpharmacy.company

medication from mexico pharmacy: mexican pharmaceuticals online – mexico pharmacies prescription drugs mexicanpharmacy.company

https://canadapharmacy.guru/# canada pharmacy world canadapharmacy.guru

canadian pharmacy meds: canadian pharmacy scam – reputable canadian pharmacy canadapharmacy.guru

buying prescription drugs in mexico online mexican drugstore online buying from online mexican pharmacy mexicanpharmacy.company

http://canadapharmacy.guru/# canadian pharmacy canadapharmacy.guru

best online pharmacies in mexico buying from online mexican pharmacy or mexico drug stores pharmacies

http://readyfirst.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=mexicanpharmacy.company mexico drug stores pharmacies

medication from mexico pharmacy buying from online mexican pharmacy and mexican drugstore online buying prescription drugs in mexico

top online pharmacy india: top 10 pharmacies in india – Online medicine order indiapharmacy.pro

77 canadian pharmacy canadian neighbor pharmacy or canadianpharmacyworld

http://www.chinanet.net/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=canadapharmacy.guru canadian pharmacy mall

canadian discount pharmacy legitimate canadian online pharmacies and reliable canadian pharmacy 77 canadian pharmacy

http://indiapharmacy.pro/# online shopping pharmacy india indiapharmacy.pro

reputable indian pharmacies: best online pharmacy india – buy medicines online in india indiapharmacy.pro

buying prescription drugs in mexico medicine in mexico pharmacies mexican mail order pharmacies mexicanpharmacy.company

indianpharmacy com indian pharmacy online or online pharmacy india

http://corporateeventplanners.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=indiapharmacy.pro reputable indian pharmacies

buy prescription drugs from india indian pharmacy and online pharmacy india india pharmacy

canadian pharmacy no scripts: canada pharmacy world – vipps approved canadian online pharmacy canadapharmacy.guru

canadian drugs pharmacy canadian pharmacy cheap or northwest canadian pharmacy

http://johnsakowicz.net/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=canadapharmacy.guru pharmacy com canada

thecanadianpharmacy maple leaf pharmacy in canada and best mail order pharmacy canada online pharmacy canada

mail order pharmacy india: best online pharmacy india – top online pharmacy india indiapharmacy.pro

https://indiapharmacy.pro/# best online pharmacy india indiapharmacy.pro

https://indiapharmacy.pro/# top 10 online pharmacy in india indiapharmacy.pro

canadian pharmacy india: indian pharmacy – canadian pharmacy india indiapharmacy.pro

mexican border pharmacies shipping to usa mexican pharmaceuticals online mexican mail order pharmacies mexicanpharmacy.company

buying from online mexican pharmacy pharmacies in mexico that ship to usa or mexican border pharmacies shipping to usa

http://piccololens.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=mexicanpharmacy.company medication from mexico pharmacy

mexican border pharmacies shipping to usa medicine in mexico pharmacies and medicine in mexico pharmacies medication from mexico pharmacy

п»їlegitimate online pharmacies india: mail order pharmacy india – indian pharmacy indiapharmacy.pro

http://indiapharmacy.pro/# Online medicine home delivery indiapharmacy.pro

online pharmacy india buy medicines online in india or canadian pharmacy india

http://tcpmux.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=indiapharmacy.pro reputable indian pharmacies

india online pharmacy п»їlegitimate online pharmacies india and india online pharmacy online pharmacy india

thecanadianpharmacy: cheapest pharmacy canada – canadian drugs canadapharmacy.guru

medicine in mexico pharmacies pharmacies in mexico that ship to usa purple pharmacy mexico price list mexicanpharmacy.company

onlinepharmaciescanada com canada pharmacy or legitimate canadian pharmacy

http://sarcasmonline.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=canadapharmacy.guru canadian discount pharmacy

best rated canadian pharmacy canadian compounding pharmacy and canadian family pharmacy canadian pharmacy

https://canadapharmacy.guru/# canadian pharmacy oxycodone canadapharmacy.guru

http://canadapharmacy.guru/# canadian pharmacy 1 internet online drugstore canadapharmacy.guru

buy medicines online in india: world pharmacy india – indianpharmacy com indiapharmacy.pro

canada pharmacy world cheapest pharmacy canada or reputable canadian pharmacy

http://temasekadvisoryservices.biz/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=canadapharmacy.guru legitimate canadian pharmacies

canadian pharmacy phone number ordering drugs from canada and canada drug pharmacy canadian pharmacy price checker

reliable canadian pharmacy reviews: canadian pharmacy ed medications – best mail order pharmacy canada canadapharmacy.guru

top online pharmacy india top 10 online pharmacy in india п»їlegitimate online pharmacies india indiapharmacy.pro

legitimate canadian pharmacies: reputable canadian online pharmacies – best canadian online pharmacy canadapharmacy.guru

buying from online mexican pharmacy best online pharmacies in mexico or п»їbest mexican online pharmacies

http://fb-insurance.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=mexicanpharmacy.company mexican border pharmacies shipping to usa

buying from online mexican pharmacy buying from online mexican pharmacy and medicine in mexico pharmacies mexico drug stores pharmacies

pharmacy website india: cheapest online pharmacy india – mail order pharmacy india indiapharmacy.pro

mexican drugstore online: reputable mexican pharmacies online – mexican mail order pharmacies mexicanpharmacy.company

indian pharmacy online pharmacy website india india online pharmacy indiapharmacy.pro

http://canadapharmacy.guru/# pharmacy com canada canadapharmacy.guru

indian pharmacy: cheapest online pharmacy india – online pharmacy india indiapharmacy.pro

https://clomid.sbs/# where can i buy cheap clomid price

https://amoxil.world/# can you buy amoxicillin uk

where can i buy generic clomid without dr prescription clomid medication where can i get generic clomid without insurance

amoxicillin pills 500 mg: where can i get amoxicillin 500 mg – medicine amoxicillin 500mg

http://amoxil.world/# amoxicillin pills 500 mg

can you buy amoxicillin over the counter in canada: amoxicillin generic brand – amoxicillin from canada

http://clomid.sbs/# cheap clomid

buying propecia online cost of generic propecia pills get propecia without insurance

https://propecia.sbs/# propecia brand name

buy prednisone 10mg prednisone 15 mg tablet prednisone online pharmacy

https://clomid.sbs/# can i buy clomid for sale

where can i buy generic clomid now: buying generic clomid without dr prescription – cost of clomid no prescription

amoxicillin 500 mg for sale amoxicillin 500mg over the counter or amoxicillin 875 125 mg tab

https://cse.google.mw/url?sa=t&url=https://amoxil.world amoxicillin cost australia

amoxicillin 800 mg price amoxicillin buy no prescription and amoxicillin 500mg no prescription can you buy amoxicillin over the counter canada

https://doxycycline.sbs/# buy doxycycline online

cost of clomid where to get clomid now where to buy generic clomid now

buy cheap propecia online: cheap propecia without rx – cost of propecia without prescription

https://clomid.sbs/# cost of clomid online

cost of propecia without dr prescription generic propecia for sale or cost propecia without prescription

http://cloud.poodll.com/filter/poodll/ext/iframeplayer.php?url=https://propecia.sbs cost of cheap propecia now

cost propecia without rx cheap propecia without insurance and order generic propecia no prescription get cheap propecia without dr prescription

where can i get amoxicillin 500 mg: how to buy amoxicillin online – where can you get amoxicillin

https://prednisone.digital/# generic prednisone otc

doxycycline generic doxycycline 50 mg doxycycline order online

http://prednisone.digital/# buying prednisone on line

buy doxycycline: generic for doxycycline – buy cheap doxycycline online

medicine amoxicillin 500mg buy cheap amoxicillin online or where to buy amoxicillin over the counter

https://cse.google.com.cu/url?sa=t&url=https://amoxil.world can i purchase amoxicillin online

amoxicillin where to get buy amoxicillin without prescription and amoxicillin cost australia amoxicillin 500mg no prescription

http://propecia.sbs/# cost of cheap propecia prices

amoxicillin 250 mg where can you buy amoxicillin over the counter generic amoxil 500 mg

http://propecia.sbs/# buying generic propecia pills

get generic propecia prices cheap propecia without dr prescription or propecia buy

http://2ch.omorovie.com/redirect.php?url=http://propecia.sbs cost propecia price

cost generic propecia without rx buy generic propecia no prescription and propecia pill cost of generic propecia

amoxicillin cephalexin: amoxicillin 500 coupon – over the counter amoxicillin

https://propecia.sbs/# get propecia without dr prescription

buy amoxicillin canada amoxicillin 500 mg tablet price amoxicillin without a doctors prescription

https://propecia.sbs/# cost of propecia without a prescription

prednisone 5084: prednisone 20mg for sale – can i buy prednisone online without prescription

http://propecia.sbs/# buy propecia tablets

buy propecia now cost generic propecia pill propecia for sale

amoxicillin 500 mg cost can you buy amoxicillin uk or amoxicillin 500 capsule

https://sofortindenurlaub.de/redirect/index.asp?url=http://amoxil.world amoxicillin 500mg pill

875 mg amoxicillin cost purchase amoxicillin online without prescription and where can i buy amoxicillin without prec amoxicillin tablet 500mg

https://doxycycline.sbs/# doxy

buying cheap propecia no prescription buy generic propecia without prescription or cheap propecia price

http://www.a-31.de/url?q=https://propecia.sbs order generic propecia without insurance

buy generic propecia without a prescription buy propecia and get propecia without rx buy generic propecia prices

purchase amoxicillin online: amoxicillin azithromycin – amoxicillin from canada

https://prednisone.digital/# prednisone 2 5 mg

amoxicillin 500mg capsule can you purchase amoxicillin online amoxicillin buy online canada

viagra without a doctor prescription: ed meds online without prescription or membership – online prescription for ed meds

http://canadapharm.top/# canada drug pharmacy

http://withoutprescription.guru/# prescription drugs canada buy online

best online pharmacy india canadian pharmacy india indianpharmacy com

п»їlegitimate online pharmacies india: indian pharmacies safe – indian pharmacy

https://canadapharm.top/# canadian pharmacy 24

http://canadapharm.top/# canadian pharmacy online ship to usa

best ed pills non prescription ed meds online buying ed pills online

https://withoutprescription.guru/# prescription meds without the prescriptions

п»їlegitimate online pharmacies india: indian pharmacy online – cheapest online pharmacy india

https://edpills.icu/# ed medications

http://edpills.icu/# non prescription ed pills

best ed pill best non prescription ed pills erection pills online

mexican rx online mexican drugstore online or mexican drugstore online

http://images.google.com.pe/url?q=https://mexicopharm.shop mexico drug stores pharmacies

mexico drug stores pharmacies mexican border pharmacies shipping to usa and medicine in mexico pharmacies mexico drug stores pharmacies

cure ed online ed pills or top ed pills

https://maps.google.ht/url?sa=t&url=https://edpills.icu ed pills that really work

[url=https://cse.google.mw/url?sa=t&url=https://edpills.icu]pills for ed[/url] medication for ed dysfunction and [url=https://www.xiaoditech.com/bbs/home.php?mod=space&uid=1433490]generic ed drugs[/url] medicine erectile dysfunction

ed prescription drugs real viagra without a doctor prescription usa or viagra without doctor prescription

http://tyadnetwork.com/ads_top.php?url=https://withoutprescription.guru/ buy prescription drugs online without

viagra without doctor prescription amazon buy prescription drugs without doctor and buy prescription drugs without doctor ed meds online without doctor prescription

mexican mail order pharmacies: п»їbest mexican online pharmacies – mexican mail order pharmacies

http://withoutprescription.guru/# buy prescription drugs online

100mg viagra without a doctor prescription viagra without doctor prescription amazon ed meds online without doctor prescription

http://edpills.icu/# ed pill

canadapharmacyonline legit canadian pharmacy king reviews or safe canadian pharmacy

http://www2.golflink.com.au/out.aspx?frm=gglcmicrosite&target=http://canadapharm.top pharmacy com canada

ed meds online canada safe online pharmacies in canada and canadian king pharmacy canadianpharmacy com

http://indiapharm.guru/# buy prescription drugs from india

online pharmacy canada Accredited Canadian and International Online Pharmacies canadianpharmacyworld

п»їbest mexican online pharmacies: buying prescription drugs in mexico online – mexico drug stores pharmacies

http://edpills.icu/# best pills for ed

mexico drug stores pharmacies mexican border pharmacies shipping to usa or mexico drug stores pharmacies

http://alt1.toolbarqueries.google.bj/url?q=https://mexicopharm.shop mexican pharmaceuticals online

medicine in mexico pharmacies mexican drugstore online and mexican online pharmacies prescription drugs best online pharmacies in mexico

legal to buy prescription drugs from canada buy prescription drugs without doctor or non prescription ed pills

http://mcclureandsons.com/projects/fishhatcheries/baker_lake_spawning_beach_hatchery.aspx?returnurl=http://withoutprescription.guru prescription drugs canada buy online

viagra without a doctor prescription prescription without a doctor’s prescription and real cialis without a doctor’s prescription viagra without doctor prescription amazon

viagra without a doctor prescription walmart prescription without a doctor’s prescription or levitra without a doctor prescription

http://www.hk-pub.com/forum/dedo_siteindex.php?q=<a+href=//withoutprescription.guru levitra without a doctor prescription

ed meds online without doctor prescription best ed pills non prescription and generic viagra without a doctor prescription generic viagra without a doctor prescription

mexico drug stores pharmacies buying prescription drugs in mexico online or п»їbest mexican online pharmacies

https://cse.google.gp/url?sa=t&url=https://mexicopharm.shop mexican drugstore online

mexican rx online mexico drug stores pharmacies and п»їbest mexican online pharmacies mexican mail order pharmacies

ed meds online without doctor prescription: prescription drugs without prior prescription – levitra without a doctor prescription

https://edpills.icu/# ed remedies

prednisone 40mg: prednisone cream over the counter – prednisone online australia

http://mexicopharm.shop/# buying prescription drugs in mexico online

legitimate canadian pharmacy Legitimate Canada Drugs canadian pharmacy

http://mexicopharm.shop/# best online pharmacies in mexico

buy prescription drugs online legally: cialis without a doctor’s prescription – ed meds online without doctor prescription

prescription meds without the prescriptions: real viagra without a doctor prescription – buy prescription drugs from india

https://edpills.icu/# pills erectile dysfunction

buying prescription drugs in mexico medication from mexico pharmacy mexican online pharmacies prescription drugs

doxycycline 100mg dogs: doxy – doxycycline without a prescription

non prescription erection pills: best ed medication – ed treatment drugs

https://canadapharm.top/# canadian online drugstore

mexican online pharmacies prescription drugs medication from mexico pharmacy or mexico drug stores pharmacies

https://cse.google.sc/url?q=https://mexicopharm.shop mexican rx online

pharmacies in mexico that ship to usa reputable mexican pharmacies online and mexican border pharmacies shipping to usa purple pharmacy mexico price list

vipps approved canadian online pharmacy buy canadian drugs or canadian pharmacy uk delivery

https://cse.google.am/url?sa=t&url=https://canadapharm.top my canadian pharmacy reviews

onlinepharmaciescanada com the canadian drugstore and precription drugs from canada cheapest pharmacy canada

https://indiapharm.guru/# reputable indian online pharmacy

viagra without doctor prescription amazon prescription meds without the prescriptions best non prescription ed pills

https://levitra.icu/# Buy generic Levitra online

Buy Vardenafil online: Buy Vardenafil online – Vardenafil online prescription

https://tadalafil.trade/# tadalafil online in india

Levitra tablet price Levitra tablet price Levitra 10 mg buy online

super kamagra: Kamagra Oral Jelly – cheap kamagra

best ed treatment top ed pills or ed pills comparison

https://secure.aos.org/login.aspx?returnurl=http://edpills.monster/ what are ed drugs

impotence pills men’s ed pills and cheapest ed pills best erectile dysfunction pills

http://sildenafil.win/# sildenafil medication

ed pills gnc: buy erection pills – п»їerectile dysfunction medication

cheap generic sildenafil citrate buy sildenafil india or sildenafil 50 mg tablet

http://maps.google.com.mm/url?q=https://sildenafil.win best prices sildenafil

sildenafil 100 capsules price generic sildenafil and sildenafil online for sale sildenafil 100mg cheap

п»їkamagra [url=http://kamagra.team/#]buy kamagra online usa[/url] Kamagra Oral Jelly

http://levitra.icu/# Buy generic Levitra online

sildenafil cream in india: sildenafil 40 mg – sildenafil online uk

best tadalafil tablets in india tadalafil uk pharmacy or tadalafil capsules 21 mg