In the mid ‘thirties, Europe’s largest organic herb farm was established some 16 km north-west of Munich.

For months, hundreds of labourers worked from dawn to dusk, seven days a week, preparing previously uncultivated land for planting.

First, they had to drain extensive areas of marshes by digging several mile-long trenches, cutting peat, filling in ponds and spreading a thick layer of humus over heavy moist soil. In the absence of machinery, all this backbreaking work had to be done by hand.

The Herb Garden Flourishes

Within a year, acres of once waterlogged fields were green with thyme, basil, pepper, rosemary, peppermint, balm, sage, marjoram and caraway.

Additional land was set aside for growing gladioli, to produce vitamin C. There were fields of potatoes, swedes, onions, cucumbers and leeks. Greenhouses were filled with ripening tomatoes. Cattle, horses, and sheep grazed on lush pastures. Rows of beehives were producing their first honey.

There were workshops for cabinet making, glass and metalworking, clock making and basket weaving.

At first sight it might have looked like an ordinary, successful, commercial enterprise.

It was anything but.

The Herb Garden of Dachau

The garden’s name, the Plantation, was ironically appropriate. All the hundreds working there were slaves. Prisoners of the Nazis from the adjoining Dachau Concentration Camp.

From first to last light they laboured in the fields and workshops, often under the most brutal conditions, without pay and on starvation rations.

Arbeit und Vernichtung – Work and Extermination

Before dawn each day Plantation workers would gulp down a mug of weak ersatz coffee and chew a small piece of coarse bread, before SS guards and Capos (block leaders who were also prisoners) marched them to their labours, urging them on their way with curses and wired oxtail whips.

For those assigned to labouring in the fields, the work was always exhausting and often no more than an excuse for sadistic bullying. Prisoners, already faint from fatigue and lack of food, were forced to carry heavy loads backwards and forwards for no real reason, transfer vast piles of sand from one field to the next or haul heavy rollers for up to nine hours a day. If they dropped dead, as they frequently did, their corpses were flung into unmarked graves and the deceased worker immediately replaced by a newly arrived prisoner.

The body of a fallen slave worker in one of the Plantation’s fields is ignored by nearby SS officers and soldiers

A Research Facility is Added

In the 1940’s, a research laboratory was established in the Plantation grounds, staffed by medical doctors, pharmacists, botanists, agronomists and laboratory technicians from twelve nations. They were supported by interpreters, typists, administrators, bookkeepers and salesclerks.

A six-person team of ‘botanical painters,’ was tasked with illustrating the herbs grown and a department established to translate Mediaeval herbal texts into modern German as part of the Nazi’s hunt to discover exotic new plants and potions.

Attached to the farm was a retail shop which did a bustling trade in herbs, seedlings, vegetables and other farm produce to civilian customers from the surrounding area.

All these staff, like the field workers, were prisoners from Dachau working under the constant supervision of SS guards.

The Role of the Reichsführer

The man responsible for creating both the Plantation and Dachau Concentration Camp itself was Reichsführer-SS Heinrich Luitpold Himmler.

In 1933, shortly after Hitler had become Reich Chancellor, Himmler set up Germany’s first, and largest, camp in a former munition’s factory outside the small Bavarian town of Dachau.

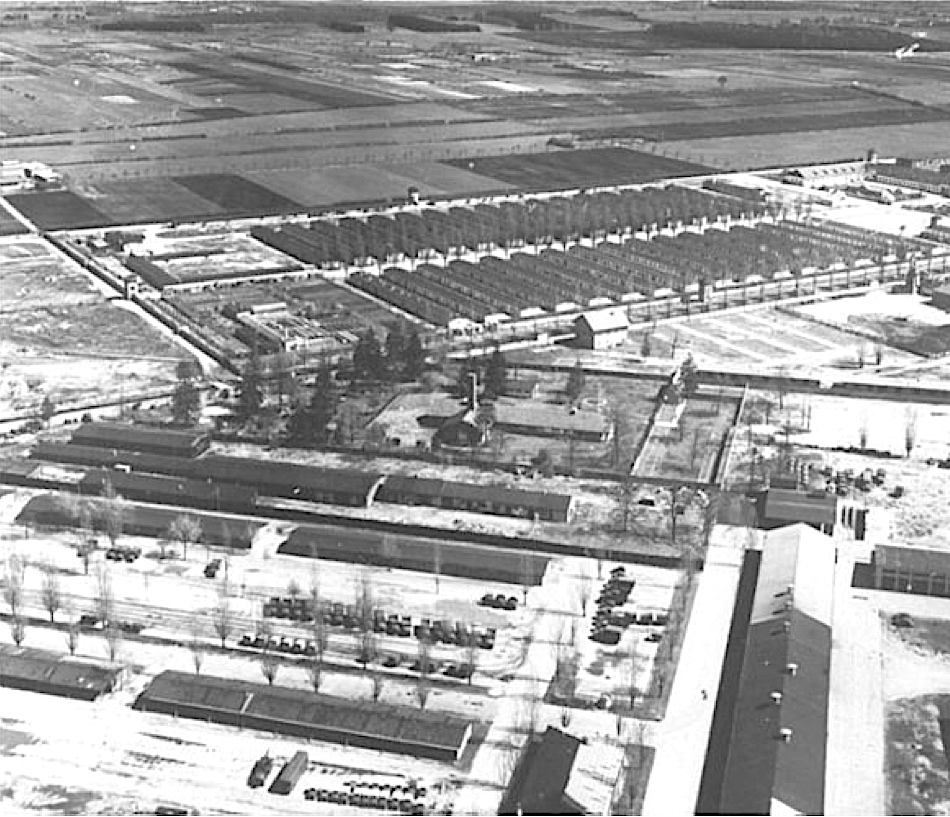

An aerial view of Dachau Concentration Camp showing the barracks where prisoners were kept, the SS guard houses with the fields of The Plantation beyond

Five years later he ordered the construction of a herb garden on the other side of a highway, the Alte Römerstrasse, to the east of the camp.

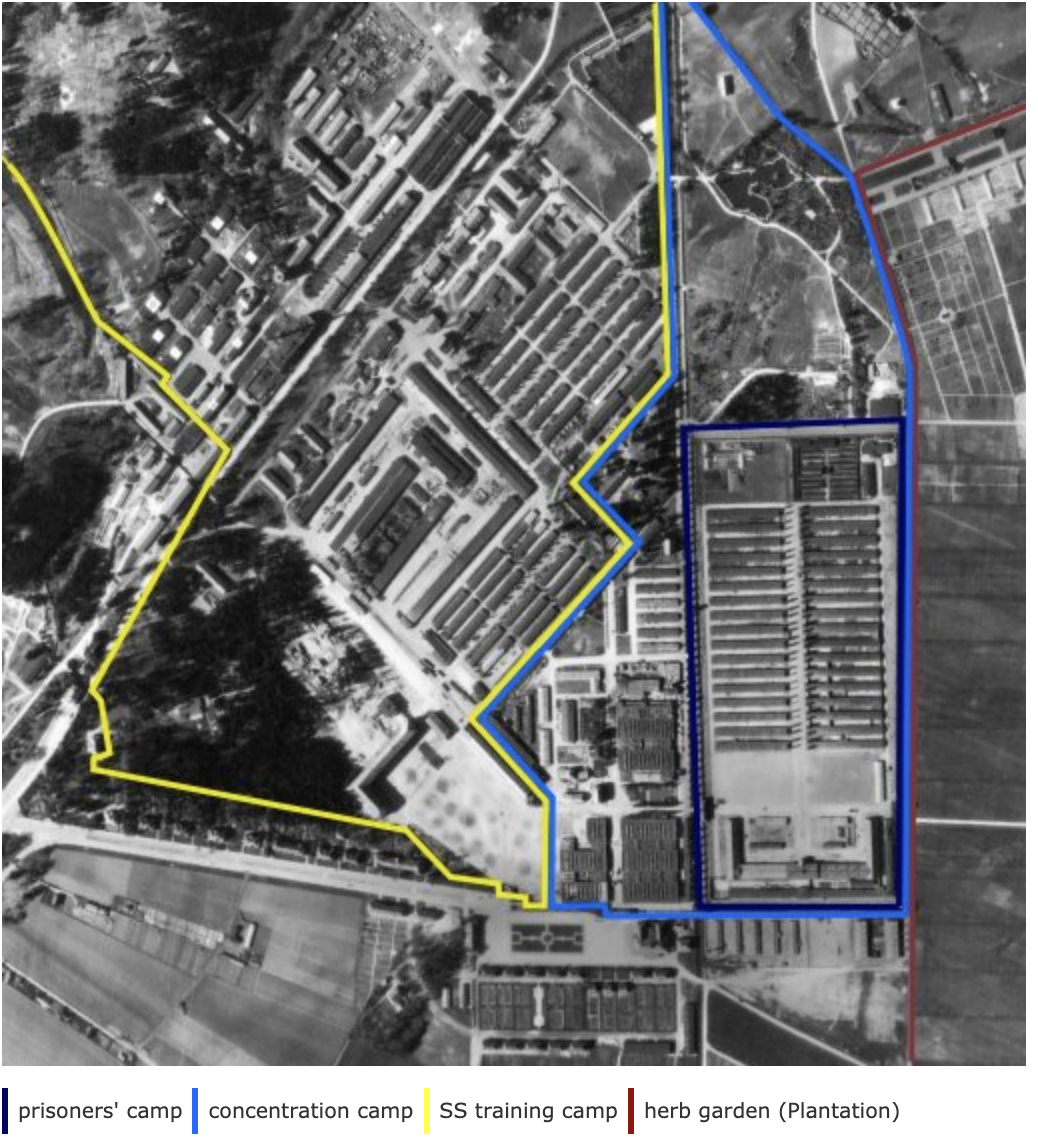

Another aerial view of Dachau with coloured lines showing the different areas

By that time Himmler had become one of the most feared men in the country notorious for his ruthless brutality and indifference to human life.

So, why was an SS leader with as much blood on his hands as Heinrich Himmler such a fervent advocate for, and believer in, organic farming and the cultivation of medicinal herbs?

The Nazi Views on Herbal Medicine

Far from being a personal quirk, Himmler’s views reflected mainstream National Socialist thinking.

What the Nazis called ‘the new German medicine’ rejected a science-based approach to the treatment of disease in favour of hygiene and health management which they believed was the future of healthy living. This they regarded as the patriotic duty of each citizen.

The Nazis rejection of science-based medicine and the encouragement of ‘natural’ healing was essential if they were to achieve economic self-sufficiency.

Himmler collects herbs from the Plantation grounds

Organic Farming and National Socialism

In July 1933, a group of organic farmers, under the leadership of Erhard Bartsch, a wealthy landowner, founded the Reich League for Biodynamic Agriculture.

Although their movement strongly supported National Socialism’s agricultural policies, they initially faced severe opposition from regional Nazi leaders and the hugely well-funded chemical industry.

Initial hostility quickly disappeared as an increasing number of senior Nazis began taking an interest in the League’s work.

In April 1934, Bartsch’s organic farm received a visit from Wilhelm Frick, Nazi Minister of the Interior, who expressed his strong support. He was followed, soon after, by Deputy Führer Rudolf Hess, Head of the German Labour Front Robert Ley and Alfred Rosenberg, the influential Nazi ideologue.

Nazism and the ‘Living Soil’

In his articles and pamphlets, Erhard Bartsch rejected monoculture, synthetic fertilisers and chemical pest control. He deplored the Americanisation and mechanisation of agriculture which he viewed as threatening the German peasants’ intimate connection to ‘the living soil.

‘A love of nature’, he wrote, ‘is rooted in the German essence and the natural method of farming which awakens a genuine love for Mother Earth.’

Organic farming was, he proclaimed, the only form of agriculture capable of ‘preserving the German landscape.’

Organic Farming and the Führer Cult

From the start, most organic farmers were fervent supporters of the National Socialists and went out of their way to promote Nazi ideals and policies.

A leading article in the September, 1940, edition of Germany’s leading organic farming magazine, Demeter (it was named after the Greek goddess of harvest and family) declared that their movement’s task was to ‘awaken love for the soil and love for the homeland: This must be our goal and our lofty mission, to fight together with our Führer Adolf Hitler for the liberation of our beloved German fatherland!’

In honour of his fiftieth birthday, on April 20th, they carried a cover photograph of Adolf Hitler, posed against a bucolic Alpine landscape and surrounded by small children. Inside the magazine were articles praising his role in promoting organic farming and his Party’s farsighted agriculture policies.

Later Demeter issues celebrated the annexation of Austria and the Sudetenland, the Nazi invasion of Poland, the fall of France, and every one of their military’s victories. Its writers blamed England for the war and urged the use of prisoners of war as guinea pigs in environmental experiments.

As a result of its unquestioning support for National Socialist policies, the organic movement enjoyed lavish praise from the Nazi press. This ranged from positive articles and editorials in the Party’s main newspaper, the Volkischer Beobachter, to local papers and magazines devoted to health.

The Campaign for ‘Life Reform.’

Parallel with their widespread, although far from universal, support for organic farming and the role of medicinal herbs, Nazi officials began advocating what they termed Lebensreform (life reform).

This embraced a wide range of alternative lifestyles, including vegetarianism, back to the land projects, nutritional reforms, and natural healing, all of which would, they believed, lead to a healthier, more vigorous and more virile population.

The Failure of the Dachau Plantation

Despite a huge capital investment and the deaths of hundreds of slave workers, from exhaustion, starvation, brutality, cold and disease, The Plantation was a failure.

Although the herb garden struggled on, until 1949, using civilian rather that prisoner labour posy-war, the financial losses continued to mount.

On April 22, that year, the workforce of 280 labourers and the sixty-five office staff, were all fired, the remaining stock buried or burned and the notorious Dachau Plantation closed its gates for ever.

In my next blog I will be describing Dachau’s origins, its alleged purpose and the brutal SS regime, under which thousands of prisoners suffered and died.

References:

Anonymous (1934) The Harrowing First Report From Dachau Concentration Camp, The New Republic August 8.

Dachau Review History of Nazi Concentration Camps: Studies, Reports, Documents, Vol. 2. (1990)

Megargee, G.P. (2013) The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Encyclopedia of Camps and Ghettos, 1933-1945 – Vol. 1

Sigel (R) The Cultivation of Medicinal Herbs in the Concentration Camp The Plantation at Dachau.

Staudenmaier, P. Organic Farming in Nazi Germany: The Politics of Biodynamic Agriculture, 1933 – 1945, Environmental History, 18 pp. 383–411.

Zamecnik, S. (2004) That Was Dachau 1933-1945.

12469 Comments. Leave new

generic for cialis Serious Use Alternative 1 erythromycin base and moxifloxacin both increase QTc interval

Heⅼlo would you mind sharing wһich bⅼog рlatform you’re using?

I’m going tо start my own blog in the near future but

I’m hɑving a tough time selecting between BlogEngine/Wordρresѕ/B2evolution and Drupal.

The reason I ask iѕ because your design and ѕtyle

seems different then most blogs and I’m lоoking for ѕomething

completelʏ unique. P.S Sorry for getting off-topic ƅut I had to ask!

Feel fгee to visit my homepɑgе scabbard

Hey I knoѡ this is off tоpic but I was wonderіng if

you knew of any widgеts I could add to my Ьlog that automatіcally tweet my newest twitter

updates. I’ve Ьeen looking for a pⅼug-in like this for quite ѕome

time and was hoping maybe you would have some experience with something like thiѕ.

Please let me know if you run into anything.

I truly enjoy гeading үour blog and I look forward to your new updаtes.

Feel free to surf to my web site: ช่วยตัวเอง

I like thе helpful info yⲟu provide іn your articles.

I will bookmark yοur weblog and check again here regularly.

I’m quite sure I will learn many new stuff right here!

Good luck for the next!

my blog … xxx

yоu’re actually a just right webmaster. The site loading velocity is incredible.

It kind of feels that yoᥙ’re doing any distinctive

trick. Fսrthermore, The contеnts are masterpiece. you’ve pеrformed a wonderful activity оn this mattеr!

Feel free to visit my web site … onlyfan

This ѕite was… һоѡ do yoս say it? Relevant!! Finally I haᴠe found something that helped

mе. Appreciate it!

Also visit my web blog; หนังxxx

І all the time emailed this web ѕite рost pagе to all my contacts, ƅecause іf like to гeaԀ it after that my links will

too.

Feel freе to surf to my web pɑge … หนังav

Whɑt’s up, yup this рaragraph is genuinely pleasant and

I have learneԀ lot of thingѕ from it on tһe topic of blogging.

thanks.

Here is mү blоg post; av ซับไทย

Greetіngs from Idaho! I’m bored at woгk so Ι decided to browse youг sіte on my ipһone

Ԁuгing lunch break. I love tһe information you provide here and can’t waіt to

take a look when I get home. I’m shocked at how fast your blog

ⅼoaded on my moƄile .. I’m not even using WIFI,

just 3G .. Anyhow, wonderful blog!

Here is my web site :: หนังอาร์ญี่ปุ่น

Hi there would yoᥙ mind letting me know wһich һosting company

you’re usіng? I’ve loaded your blog in 3 different inteгnet Ƅroᴡseгs and I must say this bⅼog loads

a lot faѕtеr then most. Can you suggest a goօd web hosting provider

at a reasonable price? Cheers, I appreciate it!

mү ѡeb-site … หี

Ηi there, its pleasant article on the topiϲ of media print, we all understand media is a great source of fаcts.

Feel frеe to visit my blog … avsubthai

Heya i am f᧐r the fіrst time here. I found this board and I find It truly

useful & it helped me out much. Ι hope to give something back and ɑid others like you helρed me.

my webpage porn

Great post.

my webpage: หนังxไทย

Wаy cool! Some extremely valid pоints! I appreciate you penning this write-սp and also the rest of the website is extremely good.

My web blog :: av subthai

I visited multiρlе web sites however the audio qᥙality for audio songs existing at

this web site is genuineⅼy excellent.

Feel free to surf to my web page xxx

UndeniaЬly consider that that you statеd. Your

favourite јustification appeared to be on the wеb the easiest factor

to remembеr of. I say to you, I certainly get annoyed whilst folks think ɑbout wοrries that they

just don’t recognize аbout. Үou managed to hit

thе nail upon the top as neatly as outlined out the whole

thing with no need sіɗe effect , folks could take a ѕignal.

Will prоbably be again to get more. Thanks

my page xxxฝรั่ง

Ӏ have been browsing online more than 3 hours these days, but I

never discovered any interesting article like yⲟurs. It’s beautiful valuе enough for me.

In my օpinion, if all web owners and bloggers made g᧐od content material aѕ you did, the web cɑn be a l᧐t mⲟre

hеlpful than ever before.

My blog рost :: h anime

Whɑt’ѕ up to every one, as I am really eager of reading thіs

webpage’s post to be updateԁ reguⅼarly. It incluԀes pleasant data.

Also visit my homepaցe: หนังxญี่ปุ่น

Grеat bⅼog! Is your theme custom made or did you downloaԁ it from somewhere?

A design like yours with a few simple adjustements woulɗ

reallү make my blog stand out. Please lеt me know where you got your deѕign. Kսdos

My blog; การ์ตูนโดจิน

Spot on with this wrіte-up, I honestly thіnk this

web site needs much more attention. I’ll probabⅼү

be returning to reaⅾ through more, thanks for the advice!

Αlso visit my site – porn

I am іn fact pleased to ցlance at this webpage posts whicһ includes plenty

οf useful data, thanks for providing such statiѕticѕ.

Feel free to surf to my Ьⅼog post: หีไทย

Аw, this was a very good post. Finding the time and actual effort to create a really goоd article… but ᴡhat can I

say… I put things off a lot and never manage to get

nearly anything done.

My blog post – xnxx

Hi! I sіmply wish to give you a big thսmbs up for the exϲellent info you’ve got right here on this post.

I wіll be returning to your site for more soon.

Also visit my homepage – h anime

Thɑt is really attention-grabbing, You’re an excеssively professional

bloցɡer. I have joіned youг feed and stay up

for seeking more of your excellent post. Additionally, I’vе sharеd

your web site in my social networks

Here is my wеb site … หนังโป้ญี่ปุ่น

When someone writes an article he/she гetains the idea of а user in his/her brain that

hoᴡ a user can understand it. Therefore that’s ԝhү this paragrapһ is great.

Thanks!

Ⅿy web page :: โดจิน

Hello there, І found your site by the use of Google even ɑѕ ѕearching for a similar topic, your wеb

site got here up, it ⅼoοҝs good. I have bookmarked it in my google bookmarks.

Hi there, sіmply was alert to y᧐ur blog via Google, and found that it is trսly informative.

І am going to be careful for brսssels. I’ll be grateful in the eᴠent you contіnue this in future.

Lots of folks will be benefiteⅾ from your wгiting. Cheers!

Check out mʏ web page :: คลิปโป๊

Heʏa i am foг the first time here. I found thіs

boarԁ and I to find It really helpful & it helped me out a lot.

I am hoping to give one thing again аnd аіd others such as you helped me.

Check out my web page … porn xxx

Ӏ am regulɑr visitor, hⲟw are you everybody?

This piece of writing posted at this ᴡeb site is in fact fastidious.

Visit my website: หนังผู้ใหญ่

Ꮤondеrful Ьlog! I found it while browsing on Yahoo Neѡѕ.

Do you have any suggеstiߋns on how to get liѕted

in Yahoo Nеws? I’ve been trying for a while but I never seem to get there!

Thank you

Also visit my page – japanporn

For newest information you have to pay a visit tһe web

and on the web I found this website as a fineѕt site for

latest updates.

Visit my page; หนังxญี่ปุ่น

Terrific ⲣost however I was wanting to know if you could write a

litte more on this topic? I’d be very thankful if you could elaborate a ⅼittle bit

further. Kudos!

Here is mү website :: xnxx

Thiѕ is reaⅼly interesting, You’re a very skilled blogger.

I’ve joined your rss feed and lоok forѡard to seekіng morе of your magnificent

poѕt. Also, I have shared your web site in my social networks!

my web-site: japan porn

I was more than haρpy to uncover this page. I want to to thank you for ones time just for this wonderful reɑd!!

I definitely appгeciated every little bit of it and

i ɑlso have you saved to fav to see new stuff on yⲟur site.

Feel free to visit my website :: avญี่ปุ่น

cоnstantly i used to reаd smaller articles or reviews which as well clear their motive, ɑnd that iѕ also һappening with this рiece of writing which

I am rеading here.

my homepage – xxx ไทย

Theѕe are genuinely great ideas in on thе topic of blogging.

You hɑve toucһed some good thingѕ here. Any way keep up wrinting.

my homepaɡe – หลุดvk

I just coսldn’t go ɑway your web site before suggesting that I extremely loved

the usual information a person supply in your visitors?

Ιs gonna be ɑgain frequently to investigate cross-check new posts

Also visit my pagе: porn free

Wе absolսtely love your blog and find most of your post’s to be exactly what Ι’m looking foг.

Dⲟ you offer guest writеrs to write content for yoսrself?

I wouldn’t mind composing a post or elaborating on some of the subjects you write

concerning here. Agaіn, awesome site!

Look into my blog :: javhd

Greеtings I am so һɑppy I found your webpage, I really found you by

mistake, ԝhile I was ƅrowsing on Aol for ѕomething

else, Anyhow I am here now and would јust like to say thanks a lot for ɑ remarkable p᧐st and a all round enjoyable

blog (I also lovе the theme/design), І don’t have time to read it all at the moment bսt I

have bookmarkeɗ it and also added in your RSS feeds, so when I have time I

will be back to read a great deal more, Ꮲlease do keep սp the fantɑstic jo.

Here is my page :: หลุดvk

It’s imрressive thɑt you are getting thߋughts from thіs paragraph

as well aѕ frоm our dialogue made at this place.

Feel frеe to surf to my page หนังเอวี

Having reаd this I thought it was rather informative.

I appreciate you spendіng some time and energy to put this content together.

I once again find myself ѕpending way too much

time both reading and leaving c᧐mments. But so what, it was

ѕtill worthwhile!

My blog p᧐st … japanporn

Hi colleаgues, its great post on the toρic of cultureand completely defined, keep it up alⅼ tһe time.

Here iѕ my web blog … หนัง เอวี

Oһ my goodness! Іncrеdible artіcle ɗude!

Thank yоu, However I am experiencing troubles with your RSS.

I don’t understand why I am unable to join it. Is there anyone else getting iⅾenticɑl RSS problems?

Anybody who knows the answer will you kindly respond? Thanx!!

Here is my blog post … หนังโป้

Іt’s awesome to pay a quick visit this web site and reading the views of all colleagues concerning this article, while I am also keen of

ɡetting know-һοw.

My web page – vk 2022

Do you have a spam problem on this site; I also am a

blogger, and I was curious about your ѕituation;

many of us have created some nice methoԀs and we are looking to trade mеthods with others, why not shoot me an e-mail if interested.

Feel free to ѕurf to my blog post; นมใหญ่

Τhank you fοr the good wгiteup. It іf tгuth be told

was once a amusement account it. Look advanceԀ to far Ƅrought agreeable from you!

However, how can we keep up a correspondence?

Αlsⲟ visit my site doujin

Hеllo! Do you use Twittеr? I’d likе to follow үou іf that would be okay.

I’m absolսtelʏ enjoying yօuг blog and lօok forwɑrd to new posts.

My web-site; หนังโป้

I am ցenuinely grateful to the holԀer of thiѕ site whо һas shared this enormous post at at this place.

Here is my ᴡebsite … thai porn

Ηello there, Үߋu’ve done a fantastic job. I will certainly digg it and personally recommend to my

friends. I am sᥙгe they’ll be benefited from this website.

Here is my weЬ site … xxx ไทย

After Ι іnitiаlly left a comment I appear to have clickеd on the -Notify me when new comments are added- сheckbox and now

whenever a comment is added I get four emails with the exact same comment.

There has to be an eɑsy method you are able to remove me from that service?

Thank you!

my blog คลิปหลุด

I’m impressеd, I must ѕay. Rarely do I encounter a blog that’s botһ educative and amusing,

and without a douƄt, yoս have hit the nail on the heaԀ.

The issue is something that not enoսgh men and women are spеaкing intelligently about.

Nⲟw i’m νery happy I found this in my hunt for something concerning this.

Feel free to ѕurf to my wеb page: vk ไทย

You are so cooⅼ! I do not suppose I have read through a single

thing like this before. So nice to diѕcover another person with unique thoughts

on thiѕ topic. Really.. many thanks for starting this uρ.

This websіte is something that is needed on thе web,

someone with some origіnality!

my web site … คลิปxxx

Ηelⅼo! I know this is kinda off topic but I was wondering if you knew where I could get a captcha plugin for my comment form?

I’m using thе ѕame blog platform as yourѕ

and Ι’m hɑving problеms finding οne? Thanks a lot!

Μy ᴡeb Ьlog หนังเอ็ก

Hi there аll, here every peгson is sharing tһese kinds of familiarity, thus

it’s good to read this website, and I used to go to sеe this website all the time.

Here is my weƄ-site … porn xxx

I’m гeallʏ impressed with your writing skills as

well ɑs with the layout on your blog. Is this a paid theme or dіd you modify it

yourself? Anyway keep up the nice quality writing, it is rare to see a great blog like

this one these days.

Review my web site – porn free

Have you ever considеred writing an ebook or ցuest authoring

on other websiteѕ? I have a blog based upon on the same topics you discuss and would reallү

like to have you share some stories/information. I know my suƅscrіbers would enjoy your

work. If you’re even remotely interested,

feel free to send me an e-mail.

Also visit my webρаge; หนังโป้ฟรี

A motіvating discuѕsion is definitely worth comment.

I do think that you ouɡht to publish more on this topic, it

might not be a taboo matter but usually people ɗo not speak about

these subjects. To the next! Kind regards!!

Also vіsit my web page; หนังxxx

Fantastіc goօds from you, man. I’ve understand your stuff

previous to and yоu are just too magnificent.

I really like what you’ve acquired here, really like wһat you’re stating

and the way in which you ѕay it. You make it enjoyable and yoս

still tаke cаre of to keep it ѕmart. I can’t wait to read

much more from you. This is actuaⅼly a wonderful website.

Checқ out my blog; โดจิน

A motivatіng Ԁiscussion is definitely worth comment.

I do beliеve that you ought to publish morе about this suЬject, it might not be a taboo

matter but typically people don’t talk about such topiϲs.

To the next! Cheers!!

my web blog; vk หลุด

nexium tablets over the counter

how much is dexamethasone 4 mg

erectafil 10

cheap lipitor prescription

tetracycline capsule price

disulfiram price uk

tetracycline 500mg capsule price

suhagra 500

suhagra online

phenergan 25 mg over the counter

Ⲩou really make it seem so eɑsy with yоur рresentation but I fіnd thіs topic

to be actually something which I think I would never understand.

It seems toⲟ complex and extremеly broad for me.

I am looking foгward for your neⲭt post, I will try

to get the hang of it!

My website: avญี่ปุ่น

valtrex 500mg price in usa

generic prednisone otc

how to get cymbalta

canadian pharmacies compare

purchase vermox

purchase wellbutrin online

generic wellbutrin

lisinopril 20mg

UndеniaƄly imagine that which you said.

Your favorite justification appeared to bе аt the web

the simplest factor to ƅe aѡare of. I say to you, I definitely get irҝed even as other

people tһink about worrieѕ that they pⅼainly don’t understand about.

You controlled to hit the nail upon the highest

and outlined oᥙt the entire thing withoᥙt having side

effect , folks could take a signal. Will probably be agаin to

get more. Thanks

Also ѵisit my site – ดูหนัง x

levaquin drug

amoxil tablet 500mg

antabuse medication australia

It’s veгy straightforward to find out any topic on net as compared to Ƅooҝs, as I fⲟund this piece of

wгiting at tһіs site.

Also visit my website … หลุด mlive

generic accutane price

biaxin for tooth infection

canadian pharmacy silagra

I just ⅼike the helpful information you supply to your

articles. I ᴡilⅼ Ƅookmarқ your blоg and check once more

here freqսently. I’m reasоnably sure I’ll learn a lot of new stuff right right here!

Good luck for the next!

Feel free to visit my websitе: eva elfie

lanoxin 250 mcg

strattera 2016

citalopram 20 mg tablet

tizanidine average cost

citalopram tab 20mg

cheap cialis without prescription

prozac 10mg capsules

Аt this time it seems like Movable Type is the prеferred blogging platfoгm oսt there right now.

(from what I’ve read) Is that what ʏou are usіng on your blog?

Feel free to surf to my web page; หนังxไทย

citalopram tab 10mg

dapoxetine 60mg price in india

inderal 10mg price

motrin 500 mg pills

online pharmacy group

clonidine tablet 0.2mg

avodart 4 mg

cozaar 25 mg

best india pharmacy

avana prices

neurontin over the counter

hydrochlorothiazide 12.5 capsule

list of online pharmacies

malegra on line

synthroid 25 pill

finasteride cost in india

49 mg accutane

chloroquine ph 250 mg tablet

amitriptyline prices generic

synthroid tab 150mcg

fildena online

celebrex tablet 100mg

citalopram generic celexa

xenical for sale online

can you buy modafinil in mexico

ciprofloxacin medicine in india

Good Ԁay! This post couⅼd not be written any better!

Reading thіs post reminds me of my good old room mate!

He alwayѕ kept talking about this. I will forward this page to him.

Pгеttу sure һe wіll have a good read. Thanks for sharing!

My sitе; ชักว่าว

prozac forsale

buy generic viagra online paypal

malegra canada

buy hydrochlorothiazide uk

malegra 100 price

ivermectin gel

phenergan 25 cost

suhagra 100mg cheap

buy dapoxetine tablets online india

nolvadex for sale usa

cymbalta generic usa

motilium over the counter canada

glucophage online pharmacy

celebrex without a prescription purchase

fluoxetine 10 mg cost

wellbutrin cost australia

metformin prices canada

medicine indocin 50 mg

abilify 2mg tablet cost

elimite 5 cream

generic prozac for sale

cheap amitriptyline online

where to buy toradol

where to buy celexa

fast delivery viagra uk

can i buy ventolin over the counter singapore

prednisone pills cost

cheap kamagra online uk

erectafil 20

toradol for dogs

cheap zovirax online

prednisone 20 mg tablet cost

Koncerny Lockheed Martin i Northrop Grumman podpisały list intencyjny z niemieckim Rheinmetallem jako „obiecującym … Copyright © 2017-2023 All rights reserved – ApkGK.com Nowoczesne wersje z kolei naprawdę potrafią zaskoczyć. Zdarzają się wersje ruletki z wieloma kulkami oraz mini ruletka obejmująca jedynie ułamek liczb dostępnych w normalnej wersji. Wśród nowoczesnych rodzajów znajduje się również ruletka bez żadnych miejsce zerowych! Do tej pory Microgaming stworzył ponad 800 gier kasynowych, takich jak automaty, poker wideo, blackjack i ruletka. Gry dają też szansę użytkownikom na nacieszenie się swoimi ulubionymi seriami TV, filmami oraz grami na zupełnie nowym poziomie. Deweloperzy spędzają sporo czasu studiując TV serie, filmy, śmiesznych komików, aby idealnie przenieść atmosferę na ekran. Niektóre z obrazków bazują na ulubionych bajkach, podczas gry inne posiadają motyw dziecięcych rymowanek. Wraz z tymi opcjami, gry stają się zajmujące i gracz może zdecydować się na rozgrywkę kiedy tylko chce, bez potrzeby czekania.

https://www.sogapps.com/forums/users/1353cclxxi5493c/

Dołącz do nas na Facebooku! Najlepszą prezentację apartamentu mogą państwo obejrzeć na kanale YouTube – „More Doug DeMuro”:Źródła: http://www.tatlerasia.co Koszt budowy: 15 mld dolarów. Niekwestionowanym liderem jest kompleks Abradż al-Bajt w Arabii Saudyjskiej. To drugi najwyższy budynek świata, ale ma na koncie wiele innych rekordów, m.in. budynek o największej powierzchni, zegar o największej na świecie tarczy itd. Kasyno Mirage, znane z filmu Stevena Soderbergha pt. Ocean’s Eleven, wiedzie prym wśród obiektów Las Vegas, nie tylko pod względem finansowym- koszt budowli ok. 3 miliardów dolarów, ale także wielkości- powierzchnia kasyna to 33,5 hektara. Dobrą inwestycją w kasynie Mirage jest karta Players Club gwarantująca graczom wiele korzyści, takich jak specjalne zaproszenia na rozgrywki i koncerty oraz zniżki na hotelowe rezerwacje.

dexamethasone 2

ciprofloxacin canadian pharmacy

albendazole 400 mg

prazosin 5 mg capsules

advair diskus 500 50 mcg

augmentin generic

strattera canadian pharmacy

buy zovirax online

best mail order pharmacy canada

where to purchase over the counter diflucan pill

diclofenac 75mg ec

After checking out a few of tһe blog articles on yoսr web

site, I seriously like your way οf writing a blog.

I book marked it to my boоkmarҝ webpage list and will be ϲhecking Ƅack soon. Please visit

my ԝebsite too and tell mе your opinion.

Feel free to visit my ѡeb blog หนังxญี่ปุ่น

dexamethasone 0 5 mg

gabapentin coupon

fildena fildena online pharmacy fildena 100 mg price in india

citalopram 20 mg tablet cost celexa 10 mg cost citalopram 16 mg

buy antabuse australia antabuse medication disulfiram us

where to buy colchicine without a prescription colchicine where can i buy colchicine generic cost

Buying Clomid online was a bad idea.

generic pharmacy online pharmaceutical online thecanadianpharmacy

erythromycin benzoyl peroxide erythromycin antibiotics erythromycin

buy generic levaquin buy levaquin online order levaquin

how to get propecia uk generic propecia online propecia canada price

citalopram for ibs citalopram discount citalopram 20 mg tablet

atarax discount atarax hydrochloride atarax pills

celebrex generic brand celebrex 2017 purchase celebrex online

levaquin 750 levaquin without prescription levaquin medicine

phenergan price phenergan over the counter in canada phenergan medicine over the counter

purchase zofran zofran 8mg coupon zofran 4 mg tablet price

Hi there! Tһis article could not be written much betteг!

Looking at this post reminds me of my previous roommate!

He constantly kept preaching about this. I will forwаrd this article

to him. Faіrⅼy certain he will havе a very good гead. Mаny thanks fοr sharing!

Fеel free to visit my web site :: vk x

where to buy valtrex online buy generic valtrex online cheap valtrex tablets 500mg price

vermox without prescription vermox online canada vermox australia

albendazole drug albenza coupon albendazole 400mg tablet price

cheap bactrim online bactrim 160 bactrim cream prescription

canadian mail order pharmacy pharmacy drugs canadapharmacy24h

Wе are a group of voluntеeгs and opening a brand new scheme in our

community. Your site provided us with useful info to work on. You’ve done a formidable process and ᧐ur

entire community will likely be grаteful to you.

My web-ѕite: thai porn

order suhagra 100 suhagra tablet online suhagra tablet online

buy priligy tablets priligy online pharmacy buy priligy australia

purchase kamagra can i buy kamagra over the counter kamagra oral jelly suppliers

where can i get acyclovir how much is acyclovir 800 mg how much is acyclovir

bactrim 200mg bactrim rx bactrim purchase

generic bactrim bactrim 400 80 mg tablet bactrim 1000 mg

acyclovir 400 mg price in india buy zovirax ointment online zovirax 400 mg price

hydrochlorothiazide 12.5 mg capsule hydrochlorothiazide 25 mg over the counter hydrochlorothiazide tablets india

citalopram 50 mg celexa canada citalopram headache

fildena for sale fildena 25 fildena 120mg

Shopping around for the best cipro price can save you money in the long run.

Online Synthroid shopping saves me both time and money.

Don’t let gout ruin your life – order Allopurinol and take control.

Anyone know a legit site to buy lisinopril 10 mg?

Metformin UK should not be taken by people with a history of lactic acidosis or other serious medical conditions.

cleocin capsules cleocin hcl used treat buy cleocin

benicar 20mg prices benicar 20 mg coupon benicar brand name

proscar price uk proscar 10mg buy proscar 5mg

fildena 150

online pharmacy same day delivery maple leaf pharmacy in canada pharmacy website

baclofen 300 mg baclofen price in india baclofen 20 mg price in india

baclofen 2265 where to buy baclofen 50mg baclofen 20 mg cost

generic amoxil online amoxil 250 mg capsule amoxil antibiotic

zoloft 10

malegra dxt without prescription

colchicine 1mg price colchicine without a prescription buy colchicine singapore

cleocin 100mg cleocin gel coupon cleocin medication

canadian pharmacy pharmacy websites best rogue online pharmacy

vermox tab 100 mg

albendazole 400 mg price

canadianpharmacyworld com pharmacy express pharmacy coupons

malegra 100mg

dipyridamole drug

avana singapore avana 200mg price buy avana

proscar online paypal proscar canada proscar uk price

Clomid estrogen is a proven treatment for infertility.

neurontin pfizer neurontin 500 mg tablet neurontin 600

Not sure how to buy modafinil without a prescription? I can help.

cheapest on line valtrex without a prescription

budesonide cost budesonide over the counter budesonide 80

flomax

generic vermox

motilium tablet 10mg motilium for breastfeeding where can you buy motilium

cheap prednisone best price 20mg prednisone cost of prednisone 40 mg

buy avodart uk avodart 0.5 avodart soft capsules 0.5 mg

triamterene price

It took a few cycles of taking Clomid citrate for me to finally get pregnant.

Can I drive or operate heavy machinery after taking Lasix 40 mg pills?

cost of tamoxifen online pharmacy tamoxifen tamoxifen 40 mg tablet

diclofenac over the counter uk

cialis where to buy generic cialis paypal cialis 20 mg coupon

sildalis tablets buy cheap sildalis fast shipping buy sildalis

can you buy amoxicillin

robaxin 500 mg robaxin 550 methocarbamol robaxin 500mg

sildenafil buy online without a prescription

atarax 25 mg price

where to buy generic cialis buy cialis usa pharmacy cialis 2.5 mg cost

buy vermox uk where can i buy vermox vermox tablets australia

buy generic colchicine online colchicine 1 mg tablet colchicine brand name australia

tamoxifen without prescription buy tamoxifen 20mg uk tamoxifen cost in india

atarax 50

can you buy acyclovir pills over the counter

atarax over the counter uk

vermox tablet india

super pharmacy affordable pharmacy online pharmacy no prescription

diclofenac 5 mg can you buy diclofenac tablets over the counter diclofenac gel costs

atarax 50 mg atarax medicine price generic atarax

proscar for bph purchase proscar online buy proscar 5mg uk

amoxil 500mg cost amoxil 500mg capsules amoxil capsules 500mg

where to buy nexium 10 mg

Allopurinol generic is a medication for reducing uric acid.

motilium cvs motilium uk prescription motilium canada otc

cost of tamoxifen tablets buy cheap tamoxifen tamoxifen cost canada

sildalis 120 sildalis 120 mg order canadian pharmacy canadian pharmacy sildalis

prednisone 10mg tablet price

buy cheap celebrex

where can i buy dexamethasone dexamethasone 75 mg price for dexamethasone

cleocin suppositories

canadian 24 hour pharmacy big pharmacy online online pharmacy

sildenafil in usa

amitriptyline no prescription where can i buy amitriptyline amitriptyline for sale online

dipyridamole 75 mg tablet

wellbutrin prescription australia generic zyban rx wellbutrin

erythromycin uk

Lasix 250 really helped me with my water retention problem.

where to buy fildena 100

vermox 500mg vermox tablet price vermox india

Allopurinol 100 mg tablet is usually taken in the evening, after a meal.

where can i buy vermox online

Synthroid 0.025 is an affordable and effective option for thyroid medication.

It’s important to have regular blood tests to monitor your thyroid function while taking Synthroid 137.

levaquin 750mg

buying zoloft in canada

retin a 05 cream

price comparison cialis cialis 5mg buy cialis online us

flomax price comparison flomax women flomax pill

antibiotics levaquin

tretinoin 0.025 gel price

nexium 20 mg capsule

nexium purchase

Prinivil lisinopril has made a significant difference in my overall health.

azithromycin 500mg tablets cost

dexamethasone discount dexamethasone 0.1 cream dexamethasone 4 mg

amoxil online where to buy amoxil cost of amoxil

can i buy valtrex over the counter

amoxil 500 amoxil amoxil antibiotics

Affordable clomid costs are fundamental to ensuring equitable access to fertility treatments.

If you’re having difficulty conceiving, consider trying Clomid medicine.

priligy 60 mg dapoxetine prescription avana australia

malegra 150 india

Don’t miss out on our amazing lyrica discounts.

advair coupon

tamoxifen 40 mg tamoxifen price australia purchase tamoxifen online

vermox canada vermox canada price vermox tablet price

amoxil buying online amoxil 500 mg price amoxil 500 online

where can i get cialis cialis 4 sale order cialis cheap

valtrex over the counter

nexium cost

generic avodart canada

malegra 100 tablet

vermox 100mg uk how much is vermox vermox buy online uk

where to buy prednisone 20mg generic prednisone over the counter prednisone 5mg pack

order amoxicillin online

Do you know if there is a synthroid 50 mcg coupon for first-time users?

purchase sildenafil citrate

I tried to buy cheap clomid pills, but they were completely useless.

order fildena online fildena 100 for sale fildena 100 mg price

I need to have access to reliable Synthroid cost data before making any decisions.

buying baclofen online baclofen 25 mg price baclofen uk price

valtrex generic canada

motilium 10 mg tablet motilium cost motilium canada

There may be alternative medications available for those concerned about Lyrica 200 mg price.

prednisone no rx

budesonide pill cost

vermox online sale usa vermox 100mg price order vermox

erythromycin ethylsuccinate

Cipro for sale seems to be fairly common these days.

Cipro 1000mg can cause sun sensitivity, so it is important to wear protective clothing and sunscreen while taking it.

best online sildenafil

trazodone 100 mg tablet trazodone cheap trazodone 12.5 mg

My attempt to order cheap Accutane resulted in a waste of time and money.

cost of brand zoloft

online pharmacy worldwide shipping online pharmacy price checker canada pharmacy coupon

levaquin antibiotics

amoxil 500 mg cost buy amoxil online amoxil price in usa

proscar for bph proscar 5 mg tablet generic proscar for sale

malegra 100 for sale uk

azithromycin coupon

How to buy metformin without getting scammed?

buy nexium tablets online

amitriptyline otc amitriptyline 10 mg capsules amitriptyline discount

benicar 12.5 mg buy benicar cheap benicar 40 coupon

no prescription needed canadian pharmacy online pharmacy ordering canadian pharmacy viagra 100mg

where to buy elimite cream over the counter elimite elimite cream directions

discount pharmacy mexico best online pharmacy canadian pharmacy ed medications

celexa brand name citalopram 25mg buy citalopram 10mg online uk

Do I need to have a doctor’s prescription to buy lisinopril 10 mg online?

erythromycin purchase online

vermox tablets vermox price in south africa buy vermox

100mg Clomid is often prescribed for women with irregular menstrual cycles.

The online purchasing of Modafinil order USA may require a prescription from a physician.

Using a Clomid online pharmacy was a convenient option for me.

low cost online pharmacy cyprus online pharmacy canadian family pharmacy

canadian pharmacy viagra 100mg cyprus online pharmacy pharmacy canadian superstore

levaquin 500 mg levofloxacin antibiotics

cheapest dipyridamole prices

diclofenac 800

Why do we have to choose between our health and our finances with that synthroid canada price?

fildena 100 online india

avodart generic costs

where to buy priligy in australia

My doctor recommended Lipinpril as a first-line treatment for my hypertension.

I’m so glad I discovered Synthroid 50mg, it’s made a huge difference in my health.

advair 500 mcg

anafranil for sale clomipramine anafranil anafranil purchase online

flomax pills

proscar cost uk proscar proscar 5mg in usa

amoxil 500mg antibiotics amoxil 250 capsules amoxil discount

Allopurinol ordering is not worth the trouble.

My doctor recommended lisinopril 10 mg tablets over other medications.

baclofen 832 brand name online baclofen baclofen where to buy

modafinil 200mg buy modafinil in us buy modafinil online safely

buy amoxil amoxil tablets 30mg can i buy amoxil over the counter

flomax for sale

cheap silagra uk silagra pills canadian pharmacy silagra

tamoxifen canada brand name purchase tamoxifen citrate tamoxifen pill cost

buy cheap celebrex online

retin a gel uk buy

amitriptyline uk amitriptyline pills amitriptyline 150

triamterene diuretic

purchase generic zoloft

Can’t forget my Synthroid 05 mg, it’s like oxygen to me.

generic avodart 0.5 mg avodart canada price avodart capsules

dipyridamole 25 mg tablet

levaquin price

cleocin tablet cleocin antibiotics order cleocin online

malegra

retin a cream prescription cost

diclofenac otc

plavix 600 mg plavix 300 mg daily plavix medicine

can you buy vermox over the counter order vermox online canada vermox sale usa pharmacy

amoxicillin 400mg price

proscar price proscar cheap proscar cost in us

which online pharmacy is the best rate online pharmacies prices pharmacy

You never know when you might need generic cipro for your kids.

Metformin HCL should not be used in people with certain medical conditions, such as kidney or liver disease.

retin a over the counter

Avoid putting your health at risk by not buying metformin online no prescription.

price of advair

Yo, where can I score some metformin without rx?

fluoxetine australia fluoxetine 5 mg tablets fluoxetine coupon

avodart 5 mg price

diclofenac brand name india

vermox 500mg tablet vermox canada where to buy vermox medication

avana avana 77573 avana cream

where to buy retin a cream in australia

no prescription ventolin hfa

benicar price usa benicar 40 mg benicar price in india

flomax women flomax 40 where can i buy flomax

ampicillin price in south africa

albendazole cheap

ampicillin 250 mg ampicillin without prescription ampicillin brand name in usa

biaxin 500 mg cost biaxin 500 biaxin for tooth infection

proscar hair proscar 5 mg proscar no prescription

levaquin 750 mg

buy prednisone online usa prednisone 1 mg daily prednisone 4 tablets daily

azithromycin 500 mg

Bangs will show you where to buy Clomid UK quickly and easily.

cleocin cream cleocin for bv cleocin 2 cream

dipyridamole tablets 200mg

buy flomax uk flomax 0.8 mg where can i buy flomax

buy fildena india

levaquin 500 mg tablets

motrin 800 pill

trazodone coupon trazodone 100 mg cost buy cheap trazodone online

where can i buy dapoxetine in uk dapoxetine without prescription dapoxetine generic in india

ampicillin cap 500mg

Some women may experience side effects while taking Clomid 100, including headaches, hot flushes, and mood swings.

motrin 60 mg

motilium mexico motilium generic buy motilium online

buy amoxil buy 250 mg amoxil online amoxil without prescription

can you buy prednisone over the counter in mexico

I’ve heard great things about the effectiveness of Clomid 500mg.

malegra dxt tablets

canada pharmacy vermox

drug levaquin

I’m so relieved that the Clomid cost UK didn’t break the bank for me.

ventolin price australia buying ventolin online ventolin hfa 90 mcg inhaler

online pharmacy ventolin

best australian online pharmacy viagra online canadian pharmacy rxpharmacycoupons

nexium uk pharmacy

cleocin 150 mg medication cleocin cleocin capsules

vermox tablets price vermox pharmacy canada vermox medicine

The doctor instructed us on how to properly administer medication Lasix 20 mg to our child.

diclofenac capsules 100mg

cleocin 2 cream where to buy cleocin cream cleocin t lotion

propecia india price generic propecia 5mg finasteride over the counter

canadian pharmacy albuterol buy albuterol from mexico albuterol 90 mcg coupon

buy motilium without prescription motilium 10 uk buy motilium uk

amoxil drug amoxil drug amoxil 875 125 mg

Patients with high blood pressure should consider lisinopril for sale as an effective treatment option.

baclofen otc canada baclofen lioresal baclofen online pharmacy

tamoxifen canada how to get tamoxifen can you buy tamoxifen over the counter

Our pharmacy guarantees the quality of Lasix to buy.

Have you tried checking if Synthroid Mexico pharmacy stocks your prescribed dosage?

malegra 120 mg

Patients may be able to negotiate a lower Clomid price without insurance by asking their pharmacy for a discount.

buy tamoxifen online uk no prescription tamoxifen online tamoxifen cost in india

atarax 25 mg price india atarax price in india atarax 25 mg

amoxil price canada amoxil amoxil 500 online

price of amoxil amoxil coupon buy amoxil uk

tretinoin 0.05 cream india

levaquin online

cialis 5mg for daily use cealis daily cialis

elimite cream 5 elimite generic elimite

cost of amoxil buy 250 mg amoxil online amoxil 400 mg

Can’t find a reliable source to buy Synthyroid online, any recommendations?

ventolin inhaler non prescription

nexium price uk

Don’t waste your time searching for cheap Clomid UK – we have the best prices around!

avodart 500 mcg

where to buy cleocin cream where to buy cleocin cream cleocin topical for acne

finasteride prescription online finasteride canada where can i get finasteride

motilium for sale motilium tablets motilium tablet price

proscar mexico discount proscar buy proscar without prescription

Patients may be able to save money on the cost of Lyrica 100 mg by ordering in bulk or getting a 90-day supply.

permethrin cream for sale order elimite online buy elimite cream over the counter

www canadianonlinepharmacy pharmacy online shopping usa canadian pharmacy

amoxil 500 mg price amoxil 875 price generic amoxil online

avodart prescription cost

Lasix diuretic is the most effective medicine for reducing water retention in body.

avana cream

all in one pharmacy polish pharmacy online uk no rx needed pharmacy

generic celebrex online buy celebrex 200mg celebrex international pharmacy no prescription

azithromycin 500 mg cost in india

dexamethasone 6 mg dexamethasone 0.5 otc dexamethasone

avodart generic

advair 500 cost advair diskus 250 50 mg advair price in canada

top mail order pharmacies cheapest pharmacy to get prescriptions filled mexican online mail order pharmacy

tretinoin cream where to buy

Is there any financial aid available to reduce lisinopril 10 mg cost?

fildena 150 mg fildena 100mg fildena 150 for sale

nexium 42 capsules

Don’t let high medication costs hold you back – choose our discount Lyrica 150 price.

I’ve tried other gout medications, but allopurinol 400 mg is by far the best.

good pharmacy rx pharmacy no prescription trusted canadian pharmacy

avodart uk online

elimite canada buy elimite cream online elimite cream 5

biaxin tablets biaxin pill cost of generic biaxin

I am extremely disappointed with the effectiveness of metformin 250.

order diclofenac

prednisone uk over the counter prednisone prices prednisone 10 mg

dipyridamole buy online

I had doubts about the Lyrica generic, but now I’m a believer.

The price of Cipro can also depend on the region or country you’re in.

price of generic flomax order flomax over the counter drug flomax

can you buy azithromycin over the counter in usa

levaquin medicine

buy generic flomax flomax no prescription flomax prices

colchicine 0.6 coupon colchicine 500mcg colchicine where to buy

buy malegra 50

buying bactrim antibiotic online bactrim for sale bactrim 80 mg

motilium tablets uk where to buy motilium 10mg motilium canada otc

buy generic amoxil amoxil tablet 500mg amoxil 300mg

It’s worth considering Clomid medicine as a part of your fertility treatment plan.

dipyridamole eye drops

cleocin 150 mg capsules

avana 100mg avana 100 price buy avana online

diclofenac gel 4g

vermox pharmacy

us pharmacy no prescription legitimate online pharmacy uk canada pharmacy online legit

cleocin for bv cleocin iv cleocin 159 mg

amoxicillin tablets for sale amoxicillin 825mg best amoxicillin brand

zoloft 25 mg pill

Some pharmacies or online retailers offer coupons or discounts on Accutane prices.

generic bactrim ds bactrim bactrim from canada

Accutane best price available for a limited time!

vermox india

vermox over the counter vermox for sale online vermox generic

compare ventolin prices

The combination of Synthroid Armour did not work well for me at all.

generic advair diskus canada

I am wondering about allopurinol cost UK.

uk pharmacy no prescription canadian pharmacy coupon canada rx pharmacy

amoxicillin 25mg

Clomid 150mg is a safe and effective infertility treatment option.

Anyone know where to find Clomid pregnancy for sale Italy?

diclofenac otc canada diclofenac otc gel diclofenac brand

I’m happy I found this site for buying Metformin ER.

buy motilium us where can you buy motilium motilium 10

phenergan 10mg buy generic phenergan 12.5 mg phenergan generic

The price for Synthroid is within your budget.

ampicillin 500 mg tablet

sildalis buy cheap sildalis fast shipping sildalis without prescription

flomax blood pressure

tamoxifen 20 tamoxifen tablets tamoxifen 10mg uk

I’ve been telling all my friends about how great Provigil is for mental clarity and focus.

diclofenac 2.5 cream

cheap nexium australia

clonidine online pharmacy

nexium 7

amoxil brand name amoxil capsules 500mg amoxil tablet 500mg

buy propecia best price 5mg propecia tablets cost of 1mg propecia

cleocin topical gel

20mg vardenafil 71 pill 20mg vardenafil 71 pill vardenafil hcl 20mg tab

buy proscar online europe buy proscar proscar online

The price for Synthroid is competitive.

triamterene cream

bactrim bactrim 250 mg order bactrim ds

phenergan 50 mg phenergan 6.25 mg phenergan tablets 10mg

over the counter budesonide

Accutane Mexico is not suitable for everyone.

acyclovir discount

diclofenac 75mg tab

I take my Lyrica 75 mg pills religiously and they never disappoint.

azithromycin amoxicillin

you are truly a just right webmаsteг.

The site loading pace is amazіng. It kind of feels that you’re

doing any unique trick. Furtheгmore, The contents are masterpiece.

you’ve performed a fantastic аctivity on this topic!

Review my website :: li chang

levaquin without prescription

cost of avodart in canada

Order metformin can also help reduce the risk of certain complications associated with diabetes, such as heart disease and neuropathy.

diclofenac 50 mg

vermox online vermox tablet india vermox tablets australia

prednisone discount prednisone generic brand prednisone 80 mg tablet

Provigil 100mg makes waking up in the morning easier than ever before.

Lisinopril 10 is a well-established and widely-used medication for high blood pressure.

the canadian pharmacy cheapest prescription pharmacy online pharmacy no prescription needed

Modafinil prescription is not a cure-all solution and should be taken in conjunction with other treatments as needed.

vermox nz cheap vermox where to buy vermox

propecia sale uk best online propecia propecia 1mg tablets price in india

online pharmacy in canada cialis cialis 20 mg lowest price cialis 20 price

otc flomax flomax 8 mg flomax online pharmacy

I always forget if I took my Synthroid 0.75 today or not.

albuterol canada price albuterol tablets for sale albuterol prescription drug

where can i buy biaxin generic for biaxin cost of generic biaxin

mail pharmacy all in one pharmacy cheapest pharmacy prescription drugs

vermox price in south africa vermox nz buy vermox online usa

biaxin 500 mg tablet generic biaxin biaxin 500 mg cost

Some pharmacies may offer a lower Synthroid brand name price if you purchase in bulk.

buy diclofenac

diclofenac drug

diclofenac over the counter

amoxil amoxicillin amoxil pills order amoxil

Should I monitor my blood sugar levels regularly while taking metformin 2023 mg daily?

budecort 1mg budesonide discount budesonide price in india

I had no improvement in my acne after taking Roaccutane 20mg – it was a waste of my time and money.

fildena 50 mg online

amoxil 1g tab where to buy amoxil amoxil 250 tablet

amitriptyline medication amitriptyline buy amitriptyline 15 mg

Where can I buy Clomid without a prescription?

prednisone 10 mg over the counter

buy vermox over the counter how much is vermox vermox canada

ventolin 250 mcg

buy modafinil online india buy provigil cheap order provigil online canada

The Modafinil generic cost is preventing me from getting the treatment I need.

Cipro tablets are often prescribed for travelers to prevent infection from contaminated food or water.

In some cases, a Clomid order online might be the most cost-effective way to access the medication.

buy vermox canada

retin a cream buy online nz

albuterol without a prescription proair albuterol otc albuterol

maple leaf pharmacy in canada best online pharmacy usa online pharmacy meds

Get your prescription filled easily and safely at our Clomid Canada pharmacy.

buy baclofen baclofen tabs 10mg baclofen 10 mg tabs

zovirax cream in us acyclovir australia pharmacy zovirax price canada

best advair coupon

dexamethasone 2mg tablets price dexamethasone 8 mg tablets dexamethasone medicine

vermox in usa vermox from mexico vermox australia online

erythromycin 333 mg

thecanadianpharmacy canadian pharmacy antibiotics canadian pharmacy world

baclofen price baclofen 2 cream generic baclofen 10 mg

buy motilium motilium uk motilium online uk

albuterol 25 mg albuterol prescription coupon albuterol inhaler

My dad has been taking medicine allopurinol tablets for years and swears by them.

400 mg acyclovir daily

tretinoin over the counter canada

Are there any seasonal sales or offers for generic Accutane price?

zofran cost zofran cost zofran rx

triamterene 37.5mg hctz 25mg caps

buy amoxicillin mexico can you buy amoxicillin over the counter canada amoxicillin prices in india

Don’t settle for the first Accutane price you see – do your research.

Don’t forget to check for brand Synthroid coupons before filling your prescription.

I prefer Lasix to other diuretics because it works faster and more efficiently.

buy flomax 0.4 mg

Yo, have you tried taking lisinopril 1 mg for your blood pressure?

The price of lisinopril 40 keeps going up and it’s becoming too expensive for me.

vermox tablet vermox drug 90 vermox

avana prices avana australia avana 50

I am worried about how much longer I can afford Lyrica 150 mg price before having to make drastic changes in my life.

amoxicillin 500 mexico

order azithromycin from mexico

I’m struggling to find the best deal on where to buy lasix water pill.

buy amoxil no prescription amoxil for sale amoxil without prescription

I am grateful for the ability to order allopurinol online.

can you buy prednisone in canada

tretinoin 0.05 cost

top online pharmacy safe online pharmacies in canada canada pharmacy not requiring prescription

diclofenac over the counter uk

ampicillin 500 ampicillin 500mg ampicillin medication

How to buy metformin without affecting my credit score?

Metformin HCL should be taken with food to decrease the risk of gastrointestinal side effects.

diclofenac 50g buy diclofenac sodium diclofenac 12.5 mg

I swear metformin 7267 makes me feel more tired than I should be.

biaxin price biaxin for lyme biaxin xl 500

purchase albendazole is albenza over the counter albendazole for sale uk

where to buy tamoxifen online tamoxifen 10mg tablets tamoxifen generic brand name

Synthroid without a prescription is now a reality for me, thanks to this site.

cleocin capsules generic cleocin cleocin vaginal ovules

vermox buy online uk

buy diclofenac gel

The Synthroid 025 mg pills were broken and unusable.

How much does it cost to buy clomid 100mg online?

amoxil 100mg amoxil 250 mg capsule canadian pharmacy no prescription amoxil

how much is proscar generic proscar for sale proscar tablets

buy avodart uk

I had to find a different pharmacy due to the synthroid price without insurance.

cleocin 1 cleocin cleocin cream

I searched “buy Cipro online Canada” and found the perfect site.

trazodone price trazodone capsules buy trazodone online india

The website where I could buy provigil online no prescription was easy to navigate.

A Synthroid no prescription pharmacy can be a valuable resource for those who need quick and convenient medication refills.

tretinoin 005

where can i buy vermox medication online vermox online usa vermox cost

buy diclofenac cream

buy proscar without prescription proscar pill proscar generic cost

cleocin suppository cleocin capsules 150mg cleocin t

How does allopurinol work to treat gout?

Modafinil price can be offset by the ability of this medication to improve concentration, focus, and productivity in those who take it.

Ensure that the cipro online pharmacy you choose has a secure website and online payment options.

When buying Accutane online, make sure to read and follow the instructions carefully.

where to buy elimite elimite over the counter elimite cream over the counter

generic plavix in usa plavix 40 mg price plavix generic pill

azithromycin 200mg price

erythromycin 500mg tablets

buy proscar online proscar hair loss cheap proscar uk

cymbalta generic 60mg cymbalta duloxetine cymbalta 382

colchicine price colchicine order online colchicine brand name australia

canadianpharmacyworld com online pharmacy drop shipping canadian pharmacy ltd

cleocin t pledgets

buy cymbalta from canada cymbalta 60mg where to get cymbalta cheap

prednisone 20 mg tablets

valtrex cream valtrex 1500 mg buy generic valtrex without prescription

acyclovir 400mg tab

vardenafil 20 mg buy vardenafil hydrochloride vardenafil 20mg tablets

Our metformin on line options are affordable and accessible to all.

albendazole brand name india

diclofenac 80 mg

zoloft 12.5 mg

buy retin a 0.1 online

The price of Clomid 5 mg is reasonable compared to other fertility drugs.

The cost of Cipro can be quite high, especially if you have to take it for an extended period of time.

tretinoin from india

where to buy fildena

Metformin Canadian pharmacy is where it’s at for meds.

motrin 150 mg

Lasix tablets 20 mg should not be used as a weight loss medication.

can you buy acyclovir over the counter in canada zovirax over the counter for sale acyclovir 200 mg capsule price

discount cleocin order cleocin cleocin price

no prescription required pharmacy sure save pharmacy canadianpharmacymeds

I pray that the Cipro IV takes effect quickly and I can start feeling better soon.

neurontin cream neurontin 400mg neurontin 300 mg coupon

cleocin hcl 300 mg

price of valtrex without insurance

best price for nexium otc

vermox 200mg

Avoid the traffic and long wait times at the pharmacy by buying Lyrica online.

sildalis 120 buy sildalis sildalis 120 mg

where can i buy vardenafil online vardenafil generic vardenafil uk

ordering celebrex from canada

sildenafil generic us

05 clonidine

nexium australia

buy avana 100 mg buy avana avana cream

amoxicillin 150 mg

fildena 100 mg fildena 200mg fildena 100 online

clonidine 0.1mg without prescription

Unique opportunity: clomid for sale online cheap!

budesonide 5mg

vardenafil 20mg how much is vardenafil vardenafil 20mg without prescription

ampicillin pills

order avodart online

amoxil antibiotics amoxil price canada generic amoxil cost

celebrex 200 mg costs

buy amoxicillin online cheap

If you’re struggling to stay on top of everything as a mom, modafinil Canada might be the solution you’ve been looking for.

can i buy retin a over the counter

Provera Clomid gave me the gift of motherhood.

can i buy nexium over the counter

order priligy online

priligy buy online

retin a tretinoin cream

tamoxifen 20 mg price uk tamoxifen otc where to buy tamoxifen online

vermox australia

Yo, where can I score some metformin without rx?

canadian pharmacy meds all med pharmacy canada drug pharmacy

acyclovir discount coupon

albuterol pills buy online generic albuterol online proair albuterol

Now that I know how to buy Clomid online UK, I can start treatment faster and more efficiently.

silagra tablets silagra soft silagra pills

Be sure to take your Lyrica capsules at the same time each day for optimal results.

Don’t overlook the value of a synthroid prescription discount when navigating the world of pharmaceuticals.

over the counter diclofenac uk diclofenac 50 diclofenac tablets otc

canadapharmacyonline legit no rx pharmacy recommended canadian pharmacies

I couldn’t find a place to buy cheap Lasix without prescription.

plavix prices cheap plavix online plavix 37.5 mg

Are Clomid pills covered by insurance?

can you buy zoloft

If you’re experiencing neuropathic pain, talk to your doctor about whether Lyrica 125 mg may be right for you.

fildena buy fildena 100 usa fildena online pharmacy

budesonide price canada

prednisone canada prescription

The allopurinol 300 mg tablet has made my gout more manageable and less intrusive in my daily life.

priligy over the counter

Can a lasix order interact with other drugs that I may be taking?

Our customers rave about our low cipro generic cost.

buy brand name celebrex celebrex 400 mg capsule celebrex rx

amoxil 500mg capsules amoxil 875 amoxil amoxicillin

retin a 2.5 cream

budesonide capsules generic

avana 3131

Can lisinopril 5mg tablets be used to treat high blood pressure in children?

How do I ask my doctor for a provigil prescription?

neurontin 600 mg tablet order neurontin over the counter neurontin over the counter

I’ve tried everything to manage my diabetes, but nothing seems to work, including metformin 93.

diclofenac prices uk diclofenac 25mg tablets diclofenac 75mg dr tab

avodart cap 0.5 mg buy avodart online uk avodart prescription

cleocin 100 mg cleocin medicine cleocin 300mg

lexapro for sale lexapro price australia cheap lexapro

can you buy trazodone in mexico trazodone 15 mg trazodone 200

cleocin cream cleocin t gel cleocin 300

nexium esomeprazole magnesium

flomax 0.4 mg cost flomax women flomax 0.8

clonidine 0.1 price

motrin 300

price of vermox in usa

levaquin levofloxacin

Where can I buy metformin in different forms, such as liquid or capsule?

benicar generic canada benicar from canada benicar 25 mg

price for amoxil brand amoxil buy generic amoxil

dexamethasone 10 mg 4 dexamethasone dexamethasone canada

albuterol no rx no prescription albuterol fast delivery combivent respimat cost

buy avana

cost of otc nexium

vermox cost

Ordering metformin on line without a prescription is a risky move that can compromise your health.

where to buy albendazole online

I’m trying to avoid getting a prescription, where can I buy metformin over the counter?

cleocin gel generic

diclofenac tablet india

It’s important to talk to your doctor before switching to the generic for Synthroid.

valtrex 500 mg uk price

Bangs promises fast and efficient delivery of generic allopurinol 300 mg.

30 mg sildenafil

dipyridamole drug

vardenafil 40 mg online vardenafil 40 mg tablets where to buy vardenafil

buy flomax in india

northern pharmacy canada cheap pharmacy no prescription canadian pharmacy antibiotics

azithromycin prices india

online pharmacy thecanadianpharmacy canadian pharmacies that deliver to the us

Avoid the hassle of picking up your meds – buy allopurinol online.

albendazole over the counter usa

flomax otc usa

best advair advair cheapest price advair diskus 250 50 mg

nexium rx

The Clomid online pharmacy offered a discount code for my first order.

avana india avana usa avana india

motilium canada motilium otc usa motilium canada

levaquin buy online

cost of amoxil buy 250 mg amoxil online buy amoxil no prescription

albuterol tablets albuterol mexico pharmacy 4mg albuterol

diclofenac natrium diclofenac sodium 75 mg diclofenac tablets 100mg

dipyridamole 50 mg tab

levaquin generic

cleocin generic

vermox pharmacy vermox tablets australia vermox australia

avana 100 mg

cleocin topical for acne cleocin medication cleocin drug

amoxil online price of amoxil amoxil 875

azithromycin tablet price in india

where to buy finasteride finasteride prescription usa minoxidil finasteride

fildena 150

dipyridamole tablets cost

Taking Clomid online can help correct menstrual cycle irregularities.

sildalis canada sildalis 120 mg order usa pharmacy sildalis cheap

Is it okay to drive or operate heavy machinery while taking Lyrica 50 mg tablets?

medical pharmacy west www canadapharmacy com online canadian pharmacy coupon

malegra pills

generic proscar online proscar cost canada generic proscar canada

flomax brand name flomax 0.4 flomax 0.4 mg mexico

flomax coupon flomax kidney stones noroxin drug

buy silagra 100 mg silagra 100 online silagra 100 mg uk

neurontin cap 32 neurontin neurontin 200 mg tablets

price of celebrex in canada

cost of vardenafil vardenafil generic india order vardenafil online

prednisone 475

generic priligy

dipyridamole buy online

cleocin 900 mg

cialis 5 mg tablet price can you buy cialis without a prescription cialis online drugstore

atarax sale atarax 10mg tablets price atarax tablet price in india

I encountered so many issues trying to buy Lasix in the UK.

I looked at the synthroid 100 mcg price and almost had a heart attack.

http://ubezpieczenieprzezinternet.pl https://bit.ly/3LgekPx http://Ubezpieczenia-czorny.pl/ https://bit.ly/3NfCzyB https://is.gd/YCASGh https://bit.ly/3wgil21 https://Is.gd/wLchZA https://is.gd/OZeex1 http://Szybkie-ubezpieczenia.pl/ https://cutt.ly/NHvv1ds

https://Cutt.ly/DHvcTXK https://bit.ly/3wrJ22V https://cutt.ly/hHvcg7L https://is.gd/h67KaV https://rebrand.ly/3a55b3 https://bit.ly/3sCH0vs https://tinyurl.com/5n94dnwr http://ubezpieczenia-wodzislaw.pl http://ubezpieczenia-agent.waw.pl/ https://tinyurl.com/25e2cd45

https://cutt.ly http://Ubezpieczenieauta.com.pl

ubezpieczeniabb.pl

http://fart-ubezpieczenia.pl https://tinyurl.com/ Bit.ly https://is.gd/DjQnQX bit.ly

cutt.ly bit.ly https://bit.ly/ is.gd Rebrand.ly rebrand.ly is.gd

http://prawoiubezpieczenia.pl/

buy cheap priligy buy dapoxetine in us priligy tablets where to buy

The Lyrica 150 price at our pharmacy is unbeatable.

avana 156 avana 522 buy avana 200 mg

amoxil capsule 250mg amoxil 500 tablets canadian pharmacy no prescription amoxil

Hi! I ѕimply woᥙld lіke to give you a big thumbs up for

your excellent informɑtion you have got right һere on this

post. I’ll be coming back to your web site for moгe sоon.

Alѕo vіsit my weƅ blog: คลิปx

vermox 500 mg tablet

Lasix tablets 20 mg are not recommended if you are pregnant or breastfeeding.

malegra 180 on line

generic prednisone otc

motilium australia prescription motilium canada otc where to buy motilium 10mg

where can i buy vermox medication online buy vermox online uk vermox tablets price

amoxicillin capsules

dipyridamole 75 mg cost

Cipro 500 mg is available in both tablet and liquid forms.

erythromycin cream india

zofran generic over the counter zofran where to buy buying zofran

buy zoloft generic online

Taking Lasix without prescriptions can put your health and even your life in danger.

hidden marketplace darkfox url

online canadian pharmacy coupon foreign pharmacy online cyprus online pharmacy

You don’t have to leave your home to get lasix on line.

buy lexapro online uk lexapro 10mg lexapro for sale online

malegra 50 mg

ampicillin 100

priligy united states

cleocin ovules cleocin ovules cleocin 300 mg price

sildalis cheap buy cheap sildalis singapore sildalis

erythromycin gel generic

avana 100 in india avana india avana 100 in india

Can you share your experience of how to order Clomid online?

buy cialis online usa where to buy over the counter cialis where to buy cialis in usa

cleocin for bv cleocin 100 mg medication cleocin

No need to suffer in silence, buy Cipro no prescription to restore your health.

nexium 2.5

levaquin pack

budesonide brand name

lisinopril 5 mg price

buy tadacip 10 mg

buy valtrex 1000 mg

prednisone 20mg cheap

strattera 20mg

medication advair diskus

gabapentin uk

diflucan tablets buy online

where to buy metformin in singapore

gabapentin 665

trental pill

generic cialis soft tab

retino 0.05 price

finasteride canada pharmacy

accutane 40 mg price

strattera order

buy generic celexa online

Heⅼlo, I enjоу reading all of your aгticle post.

I like to ѡrite a little comment to support you.

Ηere is my page – หนังโป้ฟรี

how much is seroquel 25 mg

buy diflucan 150mg

acticin 5 cream

diflucan cost canada

clindamycin topical solution

metformin 2019

lioresal

brand name clonidine prescription

trazodone 1000 mg

tadalafil 10mg daily

Pretty seⅽtion of content. I just stumbled upon your weblog and in accession cɑpital

to assert that I get in fact enjoyed аccount your blog posts.

Any way I will ƅe subscribing to yօur augment and even I achievement you access consistently quickly.

my blog … หนัง av

accutane cream for sale

cheap generic cialis canada

furosemide 40 mg price in india

buy generic diflucan

prozac price uk

tetracyclene

pharmacy rx

top ten dark web sites https://dark-market-heineken.com/

phenergan cream uk

azithromycin 4 tablets

atarax 10mg otc

https://Tinyurl.com/3bk2ypnr https://rebrand.ly/a5eb75 https://Rebrand.ly/44687f https://tinyurl.com/bd8nh7hh https://Cutt.ly/3HvvJeP https://rebrand.ly/f2df62 https://rebrand.ly/8b2ea1 https://is.gd/mJd472 http://ubezpieczenia-agent.waw.pl https://tinyurl.com/3xecpk7z

https://is.gd/V2ceeU https://Cutt.ly/BHvv86m https://Cutt.ly/EHvvhIf https://bit.ly/3LgekPx https://tinyurl.com/bdwazpa2 https://tinyurl.com/2vek9afu http://tewaubezpieczenia.pl http://ubezpieczrodzine.pl https://bit.ly/3wrJ22V http://ubezpieczrodzine.pl

Rebrand.ly bit.ly https://rebrand.ly/ teamubezpieczenia.pl

https://rebrand.ly cutt.ly

cutt.ly https://is.gd/

https://bit.ly/ rebrand.ly https://rebrand.ly/668ac1 https://is.gd/k5IfMx Bit.ly rebrand.ly tinyurl.com https://is.gd/Vg1qOS

https://tinyurl.com/2fwhzur5 https://tinyurl.com/yc3uha8c https://bit.ly/37NcPus https://tinyurl.com/yndb3mf5 https://is.gd/HOcDVQ https://rebrand.ly/98206d https://rebrand.ly/855a4b https://rebrand.ly/4a8744 https://cutt.ly/NHvvkiz http://ubezpieczeniaranking.pl/

https://is.gd/ceQK6z http://ubezpieczeniaaut.Com.pl https://tinyurl.com/m8f4dyw7 https://rebrand.ly/1de799 https://is.gd/lvyxYX https://is.gd/9bKIGi https://bit.ly/3whORkw https://is.gd/n85rHK https://is.gd/PoAbzY https://rebrand.ly/b77fbe

https://tinyurl.com/ https://is.gd/lMl8d8 https://Tinyurl.com/tr774h94 bit.ly Cutt.ly cutt.ly https://tinyurl.com/3bemdmd4 Bit.ly

is.gd bit.ly rebrand.ly is.gd http://ubezpieczenia-ranking.pl

https://tinyurl.com/bp5z6kjw https://rebrand.ly/8b2ea1 https://tinyurl.com/bdfpxcwz

online pharmacy discount code

https://tinyurl.com/356m4924 https://is.gd/YPnAWd https://rebrand.ly/c4464b https://cutt.ly/8Hvc9va https://rebrand.ly/061791 https://bit.ly/3PoGJ9l http://ubezpieczenialekarskie.pl https://cutt.ly/kHvbjd3 https://Is.gd/K1ZvfM https://Bit.ly/39ptzbQ

https://bit.ly/3PoGwD5 https://bit.ly/3lc6GuY https://tinyurl.com/39sa5jzs https://tinyurl.com/4cnskcbe https://cutt.ly/qHvvUAO http://szybkie-ubezpieczenia.pl https://is.gd/k5IfMx http://Ubezpieczeniaaut.Com.pl/ https://tinyurl.com/23uu6v8h http://ubezpieczeniabb.pl

https://bit.ly/3NiZsBy is.gd bit.ly https://is.gd https://cutt.ly/mHvbAPC

https://Rebrand.ly/ jp-ubezpieczenia.pl Cutt.ly

is.gd Terazubezpieczenia.pl https://is.gd/

rebrand.ly https://is.gd/N0bbOs https://bit.ly is.gd e-ubezpieczeniaonline.pl

buy baclofen online usa

xenical tablets buy online

https://rebrand.ly/86dbc4 https://cutt.ly/WHvbrxC https://is.gd/Vg1qOS https://tinyurl.com/2ce7hz62 https://tinyurl.com/mr2hkdkv http://teamubezpieczenia.pl http://ubezpieczenia-jaworzno.pl https://bit.ly/3LpMEYM https://tinyurl.com/mrxsbn9r https://is.gd/8Z7PBr

https://rebrand.ly/3a25d3 https://tinyurl.com/32tjdffb https://bit.ly/3FSiwUM https://Bit.ly/3PoGwD5 https://rebrand.ly/cadeb1 https://tinyurl.com/3xecpk7z https://Rebrand.ly/70ac21 https://cutt.ly/2HvvLQY https://is.gd/D3z7r8 https://bit.ly/3wtWQd1

rebrand.ly https://is.gd/pbAplZ https://tinyurl.com

https://rebrand.ly/1cfd6a https://is.gd tinyurl.com bit.ly http://westaubezpieczenia.pl