In October, 1918, a hysterically blind Adolf Hitler was transported by rail to a small mental hospital, or nerve clinic, some 600 miles from the Western Front and not far from the Polish border.

In my previous blog I described how, soon after arrival, he was successfully treated by hysteria specialist Dr Edmund Forster.

Forster used hypnosis to cure him of his blindness. In my latest book, Triumph of the Will? I describe how, during this treatment, the conviction was implanted in Hitler’s mind that he had been singled out by a superior power to lead a defeated Germany to world dominance.

The transcript of the exchange between doctor and patient, which I reported, was taken from a book entitled The Eyewitness (Der Augenzeuge).

As I explained, while this book was overtly a work of fiction, there is strong evidence that it was based on Hitler’s medical file. This had been obtained by the Czech novelist Ernst Weiß, during a meeting with Dr Forster in Paris in 1933.

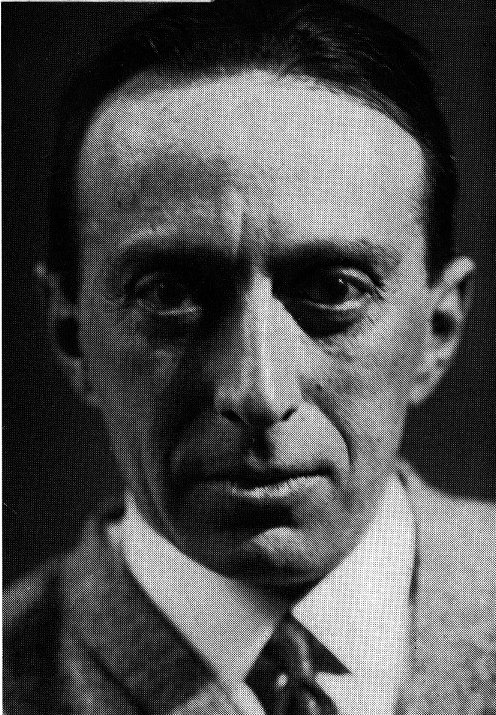

Ernst Weiß, a popular and commercially successful surgeon turned author in the twenties and early thirties. By 1938 he had fallen on hard times.

In this blog I want to explain what that evidence is and how the book came to be written in the first place.

Weiß Moves to Paris and Hires a Secretary

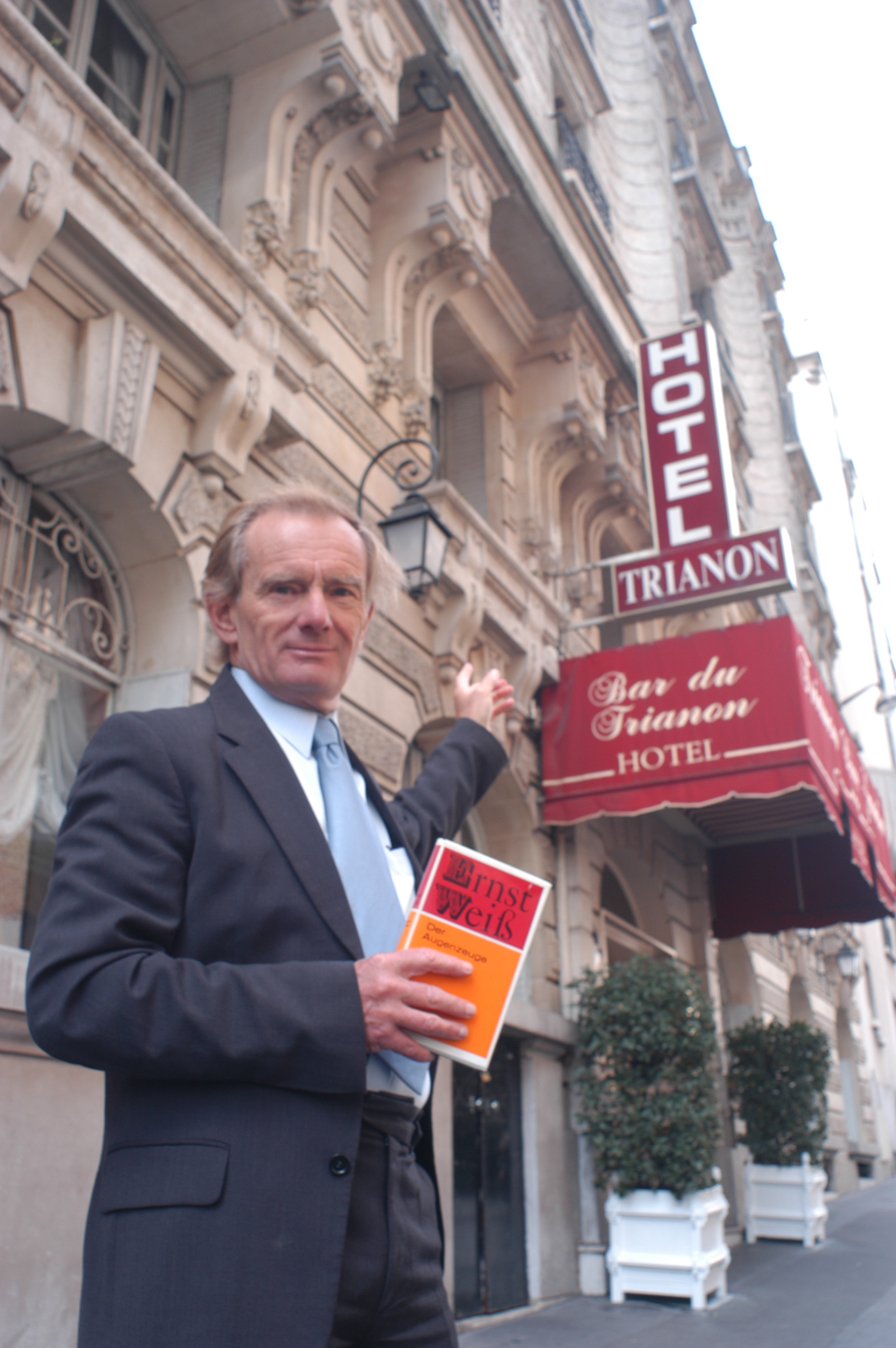

In the summer of 1936, following the death of his mother in Prague, Weiß moved to Paris. Although he had frequently visited the city over the years, this time he took up more permanent residence, renting a small room on the fifth floor of the Hôtel Trianon at 3 rue de Vaugirard, close to the Place de la Sorbonne on the left bank of the Seine.

A mutual friend introduced him to a young German-Jewish couple, Mona and Fred Wollheim.

Fred, a lawyer, worked at the Institut de Droit Comparé while Mona, a philologist who had studied at the Sorbonne, supplemented their income by giving private lessons in German, French and English.

A few months after their meeting, Weiß wrote to ask Mona if she would be willing to type the manuscript of a new novella.

She agreed and, as a result, Weiß and Mona started seeing far more of each other. He was in his fifties, she thirty years his junior.

Weiß and Mona Become Lovers

Although not conventionally handsome, Mona described Weiß to me as being ‘stocky with a bony face’, the middle-aged Czech captivated the young woman with his intellect, humour and casual talk of his famous literary friends, such as Franz Kafka, Thomas Mann and Stefan Zweig.

Before long, she began writing him poetry and soon after that they became lovers. Their affair lasted until 1938, when Mona rejected Weiß’s ultimatum that she must leave her husband.

Despite their abrupt parting, they remained friends. When, later that year, he pleaded poverty and begged her to type one final manuscript free of charge, she agreed.

Had she refused, it seems unlikely that The Eyewitness would ever have seen the light of day.

Weiß Falls on Hard Time

By early 1938, Weiß, like many exiled Jewish writers, had fallen on hard times.

France’s policy of appeasing the Nazis meant it was all but impossible to find a publisher willing to take the risk of bringing out the work of anti-Fascist émigré writers and journalists.

Even when they did, few readers showed any interest.

‘They had left behind their readers, their publishers, the magazines and newspapers that had published their works,’ says author Klaus-Peter Hinze, ‘and thus they lost their source of income.’

Weiß’s financial situation, although precarious, would have been even more desperate but for the kindness of Thomas Mann and Stefan Zweig. They arranged for the New York-based American Guild for German Cultural Freedom to pay him a stipend of thirty dollars a month.

Weiß Enters a Competition

In the summer of 1938, Weiß read an article in the German emigrant newspaper Pariser Tageszeitung that appeared to offer an escape not only from his increasingly dire existence in Paris but from France itself.

The Guild, he read, was offering a literary award for the best German novel by an exiled writer. American publishers, Little, Brown and Co. was giving the award as an advance payment for the American edition of the prizewinning novel.

The judges were to include his friends, Thomas Mann, Rudolf Olden and Bruno Frank. Entries had to be written under a pseudonym and the competition was only open to works of fiction.

Not only would winning the award solve Weiß’s financial problems, at least temporarily, it would also make it more likely that the Americans would give him a Visa to enter the United States.

His influential friends in New York and Washington were already making representations on his behalf to the State Department.

A Deadline Looms

Despite the October 1st deadline being less than a couple of months away, Weiß decided to submit an entry under the pseudonym of Gottfried von Kaiser.

While searching for a plot, he recalled his meeting, five years earlier, with Edmund Forster and decided to use Hitler’s medical notes as the basis for his story.

The Paris cafe where Edmund Forster met the emigre writers and handed over Hitler’s medical notes.

Edmund and Dirk Forster with their wives in Paris, in 1933

As stipulated in the terms of the competition, he would present the factual details of Hitler’s treatment, as a work of fiction

Weiß Sets to Work

In his pokey hotel bedroom, Weiß started writing.

The author, with a copy of The Eyewitness, outside the Hôtel Trianon, where Weiß lived and worked in a small room on the fifth floor.

For the next few weeks he barely slept or ate while racing to complete the manuscript.

With only a couple of weeks to spare, he delivered his handwritten novel to Mona who typed the clean copy. She then parcelled up the Der Augenzeuge and mailed it to New York. Once there it was added to the 239 other entries from hopeful authors.

The Novel Escapes Nazis Clutches

Weiß’s novel failed to win.

The prize went, instead, to thirty-six-year-old Arnold Siegfried Bender, who wrote under the pseudonym Mark Philippi.

By sending his manuscript out of France, however, Weiß saved it from certain destruction at the hands of vengeful Nazis.

In late June, 1940, German troops raided Mona’s apartment and carted away all the novelist’s books and papers.

‘Among the documents taken away were Weiß’ diaries,’ she told me, decades later, in New York.

Mona managed to escape from France and begin a new life in the United States.

Her husband Fred was less fortunate. Arrested by the French police, who collaborated closely with the Nazis, he perished in a French internment camp.

The Fate of The Eyewitness

Weiß’s manuscript lay gathering dust in a New York filing cabinet for over twenty years.

In 1963, a young publisher, named Hermann Kreisselmeier, agreed to its publication. But he insisted that the book should be judged purely as a literary work, with no reference being made to its likely factual basis.

It was a decision that doomed any chances of commercial success. Of five thousand copies printed in 1964, less than half had been sold a decade later.

Fiction or Fact Disguised as Fiction? You Decide

Consider these seven points and then make up your own mind.

- Weiß was a surgeon not a psychiatrist and would have had no great understanding of hysteria. Yet the details of the treatment ring true to many of the psychiatrists and hypnotherapists whom I consulted.

- As an author he was known to take situations and conversations from real life and use them, sometimes verbatim, in his novels.

- He was writing against a tight deadline to get the book ready in time for the competition’s closing date. Under these circumstances it seems very likely that a hard-pressed writer would make use of any factual details he had to hand as a source of inspiration and information.

- There is sound documentary evidence to show that he was one of a number of émigré writers and journalists who met Edmund Forster in Paris, in 1933. There is also evidence that, a sworn enemy of his former patient, Dr Forster passed to them medical evidence he hoped would discredit Hitler in the eyes of his Nazi supporters.

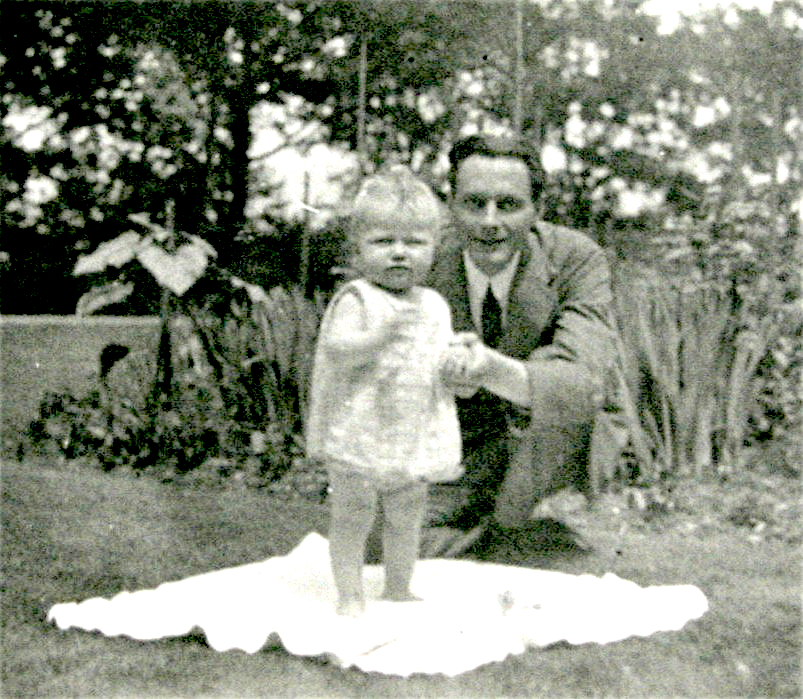

- Weiß was a close friend of Edmund’s brother Dirk. A Paris based German diplomat he and his wife frequently invited the novelist to their house, where he often played with their small daughter.

Weiß playing with Maria, the daughter of Dirk Forster, Edmund’s brother, pictured in the garden of the diplomat’s Paris home in 1931

5. The noted American historian, Rudolf Binion, was convinced that his novel perfectly describes both the character of Dr Edmund Foster and the manner in which he would treat a patient like Hitler.

6. Finally, we have the strong Nazi interest in Weiß’ work and the fact that they meticulously gathered up everything by or about him that Mona had in her files.

The Death of Weiß

On the evening Friday, June 14, 1940, the day the first German troops marched into Paris, Weiß locked himself in a bathroom at the Hôtel Trianon. Alone, abandoned and despairing of ever receiving his US Visa, the doctor turned novelist slashed at his wrists with a cutthroat razor. In his misery, this one skilled surgeon made a mess of the job. He bled slowly and painfully to death on the bathroom floor.

A Visa Was Waiting

The irony of the situation was that, unbeknown to him, his powerful friends in New York had managed to secure an exit visa for him. This was awaiting his connection at the US embassy in Paris. All they had to do was collected and leave for the safety of neutral America. No one had bothered to tell him.

In my next blog…

I will explain how Gestapo chief Heinrich Hitler, one of the most feared men in Germany, was also an enthusiastic organic farmer and operator of Europe’s largest and most successful herb gardens. These were based in Dachau concentration camp and tended,under brutal conditions, by its half-starved inmates.

12593 Comments. Leave new

excellent publish, very informative. I wonder why the other specialists of this sector don’t understand this. You must continue your writing. I’m sure, you have a huge readers’ base already!

http://www.graliontorile.com/

One desipramine study included the active comparator paroxetine in a 4 period, randomized crossover design best place to buy cialis online All About Retinoblastoma

I got good info from your blog

http://www.vorbelutrioperbir.com

You made some decent points there. I did a search on the issue and found most persons will agree with your site.

http://www.graliontorile.com/

Great web site. Lots of useful info here. I¦m sending it to a few pals ans additionally sharing in delicious. And certainly, thanks on your sweat!

https://www.vipbetflex.com

Valuable information. Lucky me I found your web site by accident, and I am shocked why this accident didn’t happened earlier! I bookmarked it.

http://www.graliontorile.com/

… [Trackback]

[…] Find More Info here on that Topic: triumphofthewill.info/the-eyewitness-fact-or-fiction-david-lewis/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Find More to that Topic: triumphofthewill.info/the-eyewitness-fact-or-fiction-david-lewis/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Find More Info here to that Topic: triumphofthewill.info/the-eyewitness-fact-or-fiction-david-lewis/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Read More on on that Topic: triumphofthewill.info/the-eyewitness-fact-or-fiction-david-lewis/ […]

I have seen that car insurance businesses know the vehicles which are vulnerable to accidents along with risks. Additionally, these people know what kind of cars are prone to higher risk along with the higher risk they’ve got the higher the actual premium charge. Understanding the straightforward basics associated with car insurance just might help you choose the right form of insurance policy that could take care of your family needs in case you happen to be involved in any accident. Many thanks sharing the particular ideas with your blog.

https://www.vonsponneck.tv/

The things i have observed in terms of pc memory is there are specific features such as SDRAM, DDR and the like, that must fit the specific features of the mother board. If the pc’s motherboard is very current while there are no operating-system issues, changing the memory space literally normally takes under a couple of hours. It’s on the list of easiest personal computer upgrade treatments one can consider. Thanks for spreading your ideas.

https://www.vonsponneck.tv/

An attention-grabbing discussion is worth comment. I believe that you should write extra on this topic, it won’t be a taboo subject but typically individuals are not enough to speak on such topics. To the next. Cheers

https://dietarysupplementu.com/foliprime-hair-formula-in-the-united-states-nourishing-your-hair-for-radiant-tresses/

Thanks for your post here. One thing I would like to say is that most professional job areas consider the Bachelor Degree like thejust like the entry level standard for an online diploma. Although Associate Qualifications are a great way to get started on, completing your Bachelors opens up many doors to various employment opportunities, there are numerous internet Bachelor Course Programs available coming from institutions like The University of Phoenix, Intercontinental University Online and Kaplan. Another issue is that many brick and mortar institutions present Online variations of their qualifications but commonly for a drastically higher payment than the institutions that specialize in online education programs.

https://businessideaso.com/how-to-become-a-credit-card-processing-reseller/

… [Trackback]

[…] Read More here to that Topic: triumphofthewill.info/the-eyewitness-fact-or-fiction-david-lewis/ […]

Great blog post. Things i would like to add is that laptop or computer memory needs to be purchased if the computer is unable to cope with whatever you do with it. One can set up two random access memory boards of 1GB each, by way of example, but not one of 1GB and one with 2GB. One should always check the manufacturer’s documentation for one’s PC to be sure what type of storage is essential.

https://hawk-play.net/

I am grateful for your post. I want to comment that the cost of car insurance varies from one plan to another, for the reason that there are so many different issues which play a role in the overall cost. For instance, the brand name of the automobile will have a tremendous bearing on the charge. A reliable older family vehicle will have a more affordable premium than just a flashy expensive car.

https://sites.google.com/view/quickbooks-intuit/home

Woah! I’m really enjoying the template/theme of this blog. It’s simple, yet effective. A lot of times it’s very difficult to get that “perfect balance” between usability and appearance. I must say you have done a amazing job with this. Also, the blog loads extremely quick for me on Firefox. Superb Blog!

https://hobitcave.com/2023/07/unveiling-enchanting-world-pixies-legends-traits-magical-delights/

You could certainly see your skills in the work you write. The world hopes for more passionate writers like you who are not afraid to say how they believe. Always go after your heart.

https://www.vonsponneck.tv/

… [Trackback]

[…] Here you will find 93887 more Information to that Topic: triumphofthewill.info/the-eyewitness-fact-or-fiction-david-lewis/ […]

A few things i have always told individuals is that while searching for a good on-line electronics shop, there are a few variables that you have to consider. First and foremost, you would like to make sure to look for a reputable plus reliable store that has received great assessments and ratings from other individuals and business sector professionals. This will ensure that you are getting along with a well-known store that provides good service and support to it’s patrons. Many thanks sharing your notions on this weblog.

https://thepartycharacters.com/hula-dancer/

… [Trackback]

[…] Find More Info here to that Topic: triumphofthewill.info/the-eyewitness-fact-or-fiction-david-lewis/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Here you can find 99064 more Info on that Topic: triumphofthewill.info/the-eyewitness-fact-or-fiction-david-lewis/ […]

f dating site: plenty of fish sign in – best online dating

I loved as much as you will receive carried out right here. The sketch is tasteful, your authored subject matter stylish. nonetheless, you command get bought an impatience over that you wish be delivering the following. unwell unquestionably come more formerly again since exactly the same nearly very often inside case you shield this hike.

https://hotnashvillestrippers.com

buy prednisone canada: http://prednisone1st.store/# prednisone tablet 100 mg

I should say also believe that mesothelioma is a exceptional form of cancer that is commonly found in those people previously exposed to asbestos. Cancerous cells form inside the mesothelium, which is a shielding lining which covers most of the body’s internal organs. These cells generally form inside lining of your lungs, abdominal area, or the sac which encircles one’s heart. Thanks for expressing your ideas.

https://hentaistgma.net/group/chandora/

One more thing. I do believe that there are numerous travel insurance internet sites of reputable companies that allow you to enter your trip details and get you the estimates. You can also purchase the actual international travel cover policy on the internet by using your current credit card. Everything you need to do is to enter your travel information and you can understand the plans side-by-side. Only find the plan that suits your allowance and needs and after that use your credit card to buy the idea. Travel insurance on the internet is a good way to take a look for a respected company pertaining to international travel insurance. Thanks for sharing your ideas.

https://addoamazon.blob.core.windows.net/dagsmejan-sleepwear-review/index.html

generic propecia for sale cost of propecia pills

buying mobic price: where buy generic mobic without prescription – mobic for sale

Say, you got a nice blog.Really thank you! Great.

https://www.fiverr.com/uptotop

I think this is a real great blog.Thanks Again.

mobileautodetailingkc.com

best canadian pharmacy online legitimate canadian online pharmacies

buying generic propecia no prescription cost of propecia

Read here.

amoxicillin 500 mg amoxicillin price canada – amoxicillin online purchase

Prescription Drug Information, Interactions & Side.

propecia no prescription buying propecia tablets

canadian pharmacy ed medications buy canadian drugs

amoxicillin 500 mg cost: http://amoxicillins.com/# where can i buy amoxicillin over the counter uk

how to get generic mobic tablets: get mobic – where can i buy mobic without a prescription

amoxicillin 500 mg tablet price buy amoxicillin without prescription – amoxicillin without prescription

where buy generic mobic without insurance get mobic for sale where can i get mobic without prescription

https://mobic.store/# how to get cheap mobic prices

Thank you, I have recently been looking for facts about this subject matter for ages and yours is the best I have located so far.

https://miamimalestripclub.com/

propecia online cost generic propecia without prescription

… [Trackback]

[…] Read More on on that Topic: triumphofthewill.info/the-eyewitness-fact-or-fiction-david-lewis/ […]

cheap ed pills: best ed pills at gnc – ed pills for sale

Read here.

cost of propecia without insurance get propecia no prescription

Comprehensive side effect and adverse reaction information.

The very root of your writing while sounding reasonable initially, did not sit properly with me personally after some time. Someplace throughout the paragraphs you actually were able to make me a believer unfortunately just for a short while. I nevertheless have got a problem with your jumps in logic and you might do well to fill in all those breaks. In the event that you can accomplish that, I could definitely be amazed.

http://www.damnrasoi.com

buy erection pills: treatment for ed – ed pills otc

best canadian pharmacy to order from canadian drug pharmacy

https://propecia1st.science/# buying propecia without insurance

medicine amoxicillin 500mg can you buy amoxicillin uk – amoxicillin 200 mg tablet

amoxil generic amoxicillin order online no prescription – amoxicillin 500mg capsule cost

This article is a refreshing change! The author’s unique perspective and thoughtful analysis have made this a truly engrossing read. I’m appreciative for the effort he has put into producing such an informative and provocative piece. Thank you, author, for offering your expertise and sparking meaningful discussions through your outstanding writing!

https://liuxuewenping.com

pharmacy rx world canada canadianpharmacyworld

https://propecia1st.science/# cheap propecia for sale

canadian online pharmacy reputable canadian pharmacy

buying cheap propecia no prescription cheap propecia without rx

ed pills gnc best ed pills non prescription compare ed drugs

Drug information.

ed medications: natural ed remedies – ed medication

Get warning information here.

ed medications list: best ed pills online – ed pills cheap

https://mexpharmacy.sbs/# mexican pharmaceuticals online

My brother recommended I might like this blog. He used to be totally right. This post actually made my day. You cann’t believe simply how a lot time I had spent for this information! Thank you!

http://mawar-toto.cvxopt.org/

After research just a few of the blog posts in your web site now, and I truly like your means of blogging. I bookmarked it to my bookmark web site checklist and will probably be checking again soon. Pls try my web site as nicely and let me know what you think.

https://mawartoto.dev-sec.io/

online pharmacy india indianpharmacy com or buy medicines online in india

http://goodjobsatusfood.net/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=indiamedicine.world indian pharmacies safe

top 10 pharmacies in india top 10 online pharmacy in india and indian pharmacies safe buy medicines online in india

п»їlegitimate online pharmacies india: indianpharmacy com – top 10 online pharmacy in india

canadian family pharmacy: canadian drug pharmacy – canadian mail order pharmacy

https://indiamedicine.world/# indianpharmacy com

best online pharmacy india indian pharmacy paypal or canadian pharmacy india

http://protectivehomeinspections.net/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=indiamedicine.world india online pharmacy

online pharmacy india online shopping pharmacy india and online pharmacy india online pharmacy india

http://certifiedcanadapharm.store/# canadian drug pharmacy

purple pharmacy mexico price list: pharmacies in mexico that ship to usa – mexico pharmacies prescription drugs

indian pharmacy paypal: buy medicines online in india – top 10 pharmacies in india

Very nice post. I just stumbled upon your weblog and wanted to say that I’ve really enjoyed surfing around your blog posts. After all I?ll be subscribing to your rss feed and I hope you write again soon!

https://strippernearme.com

https://certifiedcanadapharm.store/# cross border pharmacy canada

canadian pharmacy king reviews online canadian pharmacy or canadian drug pharmacy

http://vairagi.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=certifiedcanadapharm.store canadian pharmacy ltd

onlinecanadianpharmacy medication canadian pharmacy and pharmacy rx world canada canadian pharmacy meds

purple pharmacy mexico price list buying prescription drugs in mexico or buying prescription drugs in mexico online

http://adventuresincheese.us/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=mexpharmacy.sbs purple pharmacy mexico price list

mexico pharmacies prescription drugs mexican rx online and pharmacies in mexico that ship to usa medication from mexico pharmacy

mexican online pharmacies prescription drugs: mexican drugstore online – buying prescription drugs in mexico

п»їlegitimate online pharmacies india: online shopping pharmacy india – online pharmacy india

http://mexpharmacy.sbs/# best online pharmacies in mexico

world pharmacy india top 10 pharmacies in india or indian pharmacy paypal

http://actelis.info/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=indiamedicine.world indian pharmacy online

india pharmacy online pharmacy india and top online pharmacy india reputable indian pharmacies

Hello, I think your website might be having browser compatibility issues. When I look at your blog site in Chrome, it looks fine but when opening in Internet Explorer, it has some overlapping. I just wanted to give you a quick heads up! Other then that, superb blog!

https://www.netcomdirect.com/how-cash-discount-merchant-processing-works/

http://certifiedcanadapharm.store/# canada drug pharmacy

buy prescription drugs from india reputable indian online pharmacy or indian pharmacy

http://galerie-au-chocolat.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=indiamedicine.world reputable indian online pharmacy

world pharmacy india best online pharmacy india and online shopping pharmacy india cheapest online pharmacy india

best canadian pharmacy online: canadian medications – is canadian pharmacy legit

online pharmacy india: reputable indian online pharmacy – indian pharmacy online

http://certifiedcanadapharm.store/# canadian pharmacy near me

purple pharmacy mexico price list mexico drug stores pharmacies or reputable mexican pharmacies online

http://sarahspage.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=mexpharmacy.sbs п»їbest mexican online pharmacies

mexican mail order pharmacies п»їbest mexican online pharmacies and medicine in mexico pharmacies mexico drug stores pharmacies

best online pharmacies in mexico: mexican pharmaceuticals online – buying prescription drugs in mexico

With havin so much content and articles do you ever run into any issues of plagorism or copyright violation? My site has a lot of exclusive content I’ve either authored myself or outsourced but it appears a lot of it is popping it up all over the internet without my authorization. Do you know any techniques to help reduce content from being stolen? I’d truly appreciate it.

https://businessideascenter.com/how-to-start-a-payment-processing-company/

http://certifiedcanadapharm.store/# canadian medications

http://certifiedcanadapharm.store/# canadian family pharmacy

mexican online pharmacies prescription drugs: mexican drugstore online – mexican online pharmacies prescription drugs

top online pharmacy india india pharmacy or best india pharmacy

http://syriasale.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=indiamedicine.world best india pharmacy

buy prescription drugs from india mail order pharmacy india and indian pharmacies safe reputable indian pharmacies

reputable mexican pharmacies online: purple pharmacy mexico price list – mexico drug stores pharmacies

http://certifiedcanadapharm.store/# my canadian pharmacy rx

canadian pharmacy reviews: canadian pharmacy in canada – canadian pharmacy scam

http://mexpharmacy.sbs/# mexican mail order pharmacies

http://azithromycin.men/# where to get zithromax over the counter

ivermectin gel: ivermectin 6mg dosage – ivermectin 5 mg price

neurontin medicine neurontin tablets 300mg or neurontin cream

http://humorforthetumor.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=gabapentin.pro drug neurontin 20 mg

neurontin price neurontin generic cost and neurontin 300 mg tablets neurontin prices generic

zithromax over the counter zithromax cost uk or zithromax price south africa

http://wefeedamerica.co/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=azithromycin.men where to buy zithromax in canada

zithromax 500 mg for sale zithromax generic price and buy zithromax 1000 mg online zithromax 250 price

https://stromectolonline.pro/# ivermectin iv

neurontin uk neurontin or gabapentin online

https://forum.83metoo.de/link.php?url=gabapentin.pro neurontin 800 mg capsules

buy gabapentin neurontin 400mg and gabapentin order neurontin online

neurontin 800 mg tablets: neurontin online pharmacy – neurontin brand name 800mg best price

neurontin generic neurontin 400mg where to buy neurontin

http://gabapentin.pro/# where to buy neurontin

http://gabapentin.pro/# neurontin 600mg

ivermectin coronavirus cost of ivermectin medicine or ivermectin 2%

http://dental-directions.net/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=stromectolonline.pro generic ivermectin for humans

ivermectin cost uk ivermectin 2% and ivermectin 9 mg ivermectin 400 mg brands

neurontin 300 mg pill: neurontin 300 mg price in india – neurontin brand name

neurontin brand name in india neurontin 800 mg cost or prescription medication neurontin

http://plasticsinelectronics.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=gabapentin.pro order neurontin online

neurontin price india neurontin rx and neurontin prescription online neurontin prices generic

cost of neurontin 800 mg gabapentin buy or neurontin capsule 400 mg

http://bierman.us/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=gabapentin.pro medication neurontin

generic gabapentin neurontin 400 mg and neurontin 300 mg price neurontin 300 mg price in india

http://stromectolonline.pro/# ivermectin purchase

http://azithromycin.men/# how much is zithromax 250 mg

zithromax generic price buy zithromax 1000mg online or buy zithromax online cheap

http://omcstringers.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=azithromycin.men zithromax online usa

zithromax cost can i buy zithromax over the counter and cost of generic zithromax buy generic zithromax online

Heya i?m for the first time here. I found this board and I find It really useful & it helped me out a lot. I hope to give something back and help others like you aided me.

https://labelsuperrecords.com/white-label-merchant-payment-gateways-how-they-work/

cost of ivermectin ivermectin gel ivermectin 10 mg

What?s Taking place i am new to this, I stumbled upon this I have discovered It positively useful and it has helped me out loads. I am hoping to give a contribution & help other users like its helped me. Great job.

https://liquidhelpenergy.com/

https://paxlovid.top/# Paxlovid over the counter

Over the counter antibiotics pills: buy antibiotics for uti – best online doctor for antibiotics

paxlovid generic: paxlovid buy – paxlovid price

Thanks for your blog post. I would like to say that the health insurance specialist also works best for the benefit of the particular coordinators of the group insurance policy. The health insurance professional is given a listing of benefits needed by an individual or a group coordinator. Such a broker may is look for individuals or perhaps coordinators which usually best match those desires. Then he reveals his suggestions and if all parties agree, the broker formulates a legal contract between the two parties.

https://keyweststripclubs.com/

http://antibiotic.guru/# buy antibiotics over the counter

best erection pills ed medication online or ed pills online

http://alexmpayne.org/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=ed-pills.men ed medication

generic ed pills ed medication and otc ed pills men’s ed pills

https://avodart.pro/# can you buy generic avodart no prescription

https://lisinopril.pro/# lisinopril discount

lisinopril in mexico lisinopril 10 mg price lisinopril 20 mg discount

http://lisinopril.pro/# zestril 5mg price in india

Howdy! I know this is kinda off topic nevertheless I’d figured I’d ask. Would you be interested in trading links or maybe guest authoring a blog article or vice-versa? My website covers a lot of the same subjects as yours and I believe we could greatly benefit from each other. If you happen to be interested feel free to send me an email. I look forward to hearing from you! Excellent blog by the way!

https://officeblock.io

http://misoprostol.guru/# Abortion pills online

buy lisinopril 20 mg online: zestoretic generic – lisinopril online canadian pharmacy

https://lisinopril.pro/# lisinopril average cost

buy cipro online without prescription buy cipro online canada cipro 500mg best prices

I was suggested this blog by my cousin. I’m not sure whether this post is written by him as nobody else know such detailed about my difficulty. You’re wonderful! Thanks!

https://bettertrendzz.com/steps-to-take-to-open-a-bank-account-for-a-teenager/

http://avodart.pro/# cost of cheap avodart

Cytotec 200mcg price Abortion pills online or Cytotec 200mcg price

http://askthree.me/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=misoprostol.guru buy cytotec

buy cytotec over the counter buy cytotec pills and Misoprostol 200 mg buy online buy misoprostol over the counter

where to get avodart without rx avodart sale or how to get cheap avodart without insurance

http://orgsucks.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=avodart.pro how to get avodart without a prescription

buying avodart no prescription can you buy generic avodart and where to get cheap avodart can you buy generic avodart no prescription

http://lipitor.pro/# lipitor 10mg tablets

cytotec pills buy online buy cytotec online buy cytotec online

http://ciprofloxacin.ink/# ciprofloxacin

lipitor 40 mg price australia: lipitor buy – where to buy lipitor

http://lisinopril.pro/# 50mg lisinopril

lipitor 10mg generic generic lipitor generic lipitor prices

http://lisinopril.pro/# prinivil 25mg

lipitor 20 mg pill lipitor 10 or lipitor 40 mg tablet

http://pyreneanshepherdclub.org/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=lipitor.pro lipitor otc

lipitor 80 mg tablet lipitor 100mg and lipitor 20 mg generic lipitor generic canada

http://ciprofloxacin.ink/# buy cipro online without prescription

http://lisinopril.pro/# buy prinivil

cytotec abortion pill cytotec buy online usa cytotec online

hello!,I like your writing very a lot! share we keep in touch extra about your post on AOL? I require a specialist on this area to unravel my problem. May be that’s you! Taking a look forward to look you.

https://www.thedailyload.com/surf-the-web-for-quick-cash-payday-loans/

http://lisinopril.pro/# generic prinivil

Misoprostol 200 mg buy online buy cytotec or buy cytotec in usa

http://windowtowellness.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=misoprostol.guru cytotec online

Misoprostol 200 mg buy online buy cytotec online fast delivery and purchase cytotec Misoprostol 200 mg buy online

can i order avodart cost of generic avodart pill or can i get cheap avodart without a prescription

http://leesburg.pro/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=avodart.pro can you get avodart without prescription

can you buy avodart without dr prescription avodart generic and buy cheap avodart no prescription get avodart pill

http://ciprofloxacin.ink/# ciprofloxacin generic price

https://lipitor.pro/# canada prescription price lipitor

buy cipro cheap cipro 500mg best prices ciprofloxacin 500mg buy online

lipitor brand name lipitor generic brand name or lipitor 10mg tablets

http://ultimateautomotiveexperience.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=lipitor.pro lipitor 10

lipitor 80 mg cost lipitor 10mg price and lipitor 100mg cost of lipitor 20 mg

https://ciprofloxacin.ink/# buy ciprofloxacin

ciprofloxacin generic price ciprofloxacin over the counter or п»їcipro generic

http://eastmetrorealestatetoday.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=ciprofloxacin.ink cipro pharmacy

buy cipro without rx buy cipro online without prescription and ciprofloxacin generic ciprofloxacin

order cheap avodart online: buying cheap avodart online – can i buy generic avodart without insurance

https://misoprostol.guru/# Misoprostol 200 mg buy online

cost of lisinopril 30 mg lisinopril online lisinopril 80 mg tablet

I believe one of your adverts caused my internet browser to resize, you may well want to put that on your blacklist.

https://mawartoto.iainfmpapua.ac.id/

http://certifiedcanadapills.pro/# canadian pharmacy world

canada pharmacy canadian pharmacy prices or best canadian pharmacy online

http://blueroadspower.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=certifiedcanadapills.pro canada pharmacy world

real canadian pharmacy reputable canadian online pharmacies and canadian pharmacy canadian pharmacy checker

https://indiapharmacy.cheap/# Online medicine home delivery

trustworthy canadian pharmacy: best canadian pharmacy to buy from – canadianpharmacyworld com

Thanks for sharing your ideas. A very important factor is that students have a selection between federal student loan along with a private education loan where it’s easier to opt for student loan consolidating debts than in the federal education loan.

https://www.china-magnetics.com/products/neodymium-magnets-of-20000.html

canadian pharmacy world reviews canadian pharmacy drugs online or ed meds online canada

http://familymedfoundation.org/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=certifiedcanadapills.pro canadian pharmacies that deliver to the us

canada drugs online canadian online pharmacy and reputable canadian pharmacy buying from canadian pharmacies

mexico drug stores pharmacies: mexico drug stores pharmacies – reputable mexican pharmacies online

Hey there! I know this is kind of off topic but I was wondering if you knew where I could find a captcha plugin for my comment form? I’m using the same blog platform as yours and I’m having trouble finding one? Thanks a lot!

https://miamisuperhero.com/rent-santa-for-hire/

generic cialis no prescription australia cialis (generic) or generic cialis priligy australia

http://schillerglobal.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=cialis.science cialis buy india

buying cialis online canadian order best place to buy cialis online forum and super cialis best price cialis online overnight delivery

Hi there, I found your web site via Google while looking for a related topic, your web site came up, it looks good. I’ve bookmarked it in my google bookmarks.

https://miamisuperhero.com/rent-santa-for-hire/

Hi there! Quick question that’s completely off topic. Do you know how to make your site mobile friendly? My weblog looks weird when viewing from my iphone4. I’m trying to find a theme or plugin that might be able to fix this issue. If you have any suggestions, please share. Many thanks!

http://www.shivarealty.co.in

Kamagra tablets 100mg order kamagra oral jelly or order kamagra oral jelly

http://xafeer.biz/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=kamagra.men cheap kamagra

kamagra oral jelly kamagra and Kamagra tablets kamagra oral jelly

Incredible! This blog looks exactly like my old one! It’s on a entirely different topic but it has pretty much the same page layout and design. Superb choice of colors!

https://watermanaustralia.com/product/mineral-water-bottling-plant/

Hi my loved one! I wish to say that this article is awesome, nice written and come with almost all significant infos. I would like to look extra posts like this .

https://www-tk2019.com/reject-debit-card-producing-apply-hard-cash-exclusively-never/

Kamagra tablets kamagra or order kamagra oral jelly

http://meetingsaeriens.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=kamagra.men kamagra oral jelly

Kamagra tablets Kamagra tablets and Kamagra Oral Jelly buy online buy kamagra online

pills for ed ed meds online without doctor prescription or best erection pills

http://kristencoxphotography.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=edpill.men best ed pills at gnc

best erection pills buying ed pills online and pills erectile dysfunction new treatments for ed

you might have an awesome weblog here! would you wish to make some invite posts on my blog?

https://learncswithus.com/2023/08/26/e4bba3e58699e6a188e4be8b-mongodb-query/

Hi there, You’ve done an excellent job. I will certainly digg it and personally suggest to my friends. I’m confident they will be benefited from this site.

https://sight-web.com/6th-direct-questions-for-choosing-merchant-services/

neurontin generic cost generic neurontin 300 mg or neurontin

http://veteransinchrist.org/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=gabapentin.tech medication neurontin 300 mg

neurontin capsules 100mg cost of brand name neurontin and prescription drug neurontin neurontin 600mg

I realized more interesting things on this weight-loss issue. 1 issue is that good nutrition is especially vital whenever dieting. A tremendous reduction in fast foods, sugary ingredients, fried foods, sweet foods, pork, and whitened flour products could be necessary. Holding wastes parasitic organisms, and poisons may prevent desired goals for losing weight. While a number of drugs temporarily solve the challenge, the horrible side effects are not worth it, and they never offer more than a non permanent solution. It is a known undeniable fact that 95 of celebrity diets fail. Many thanks for sharing your opinions on this blog.

https://mawar-toto.sgp1.cdn.digitaloceanspaces.com/index.html

п»їorder stromectol online stromectol 0.5 mg or ivermectin 1 cream generic

http://thebalaneseline.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=ivermectin.today ivermectin generic cream

ivermectin gel where to buy ivermectin pills and stromectol tablet 3 mg stromectol online

I’m really enjoying the theme/design of your web site. Do you ever run into any web browser compatibility issues? A few of my blog readers have complained about my site not working correctly in Explorer but looks great in Firefox. Do you have any recommendations to help fix this issue?

https://vip777.info

I?ve been exploring for a little bit for any high-quality articles or blog posts on this sort of area . Exploring in Yahoo I at last stumbled upon this web site. Reading this info So i?m happy to convey that I’ve an incredibly good uncanny feeling I discovered just what I needed. I most certainly will make sure to do not forget this website and give it a glance on a constant basis.

http://simak.poltektegal.ac.id/Data/?tunnel=MAWARTOTO

ivermectin cost uk stromectol 3 mg price or ivermectin 50

http://iceluxurycollection.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=ivermectin.today ivermectin 500ml

stromectol nz ivermectin for humans and stromectol cost ivermectin 6mg

Level up while tipping girls in chat rooms and enjoy the BEST new live cam site experience https://cupidocam.com/content/tags/blonde

ivermectin 6 ivermectin 500ml or stromectol prices

http://statenislandboro.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=ivermectin.auction price of ivermectin

stromectol cost ivermectin 2mg and ivermectin 3 mg tabs ivermectin cream 1%

furosemide lasix generic name or lasix furosemide

http://gsfonline.org/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=lasixfurosemide.store furosemida

buy lasix online furosemida 40 mg and lasix pills buy furosemide online

ivermectin buy australia ivermectin 1mg or ivermectin 18mg

http://object01.info/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=ivermectinpharmacy.best ivermectin lotion

stromectol buy ivermectin cream cost and stromectol medication ivermectin 3 mg tablet dosage

What i don’t understood is actually how you are not really much more well-liked than you may be now. You are so intelligent. You realize thus significantly relating to this subject, made me personally consider it from numerous varied angles. Its like men and women aren’t fascinated unless it?s one thing to do with Lady gaga! Your own stuffs nice. Always maintain it up!

https://danbammassage.com/incheon-massage/

You could definitely see your enthusiasm in the work you write. The world hopes for even more passionate writers like you who are not afraid to say how they believe. Always go after your heart.

https://telegramim.com/

neurontin pills for sale neurontin 300 mg capsule or neurontin singapore

http://www.plumfarms.net/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=gabamed.store neurontin 100mg tablets

neurontin 300mg caps neurontin 300 mg price in india and buying neurontin online buy neurontin 100 mg

ivermectin cost canada ivermectin pills human or stromectol south africa

http://journeystartsnow.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=ivermectinpharmacy.best stromectol tablets for humans

ivermectin human ivermectin 6mg dosage and ivermectin brand name ivermectin lice

Thanks, I’ve been hunting for info about this subject for ages and yours is the best I have located so far.

https://www.edotmagazine.com/the-career-of-selling-merchant-accounts-good-internet-job-career/

indian pharmacy paypal buy prescription drugs from india or cheapest online pharmacy india

http://anglo-mauritius.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=indiaph.ink Online medicine home delivery

online pharmacy india best india pharmacy and buy medicines online in india reputable indian pharmacies

canadian pharmacy 24 com: certified online pharmacy canada – canadian pharmacy sarasota

canadian pharmacy no scripts pharmacy in canada or recommended canadian pharmacies

http://sesq.sa.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=canadaph.pro canadian pharmacy meds reviews

canadian pharmacy uk delivery best rated canadian pharmacy and online canadian drugstore ed drugs online from canada

medication from mexico pharmacy: buying prescription drugs in mexico – mexico drug stores pharmacies

I was suggested this website by my cousin. I am not sure whether this post is written by him as no one else know such detailed about my problem. You’re wonderful! Thanks!

https://www.hilaud.com/Products/Bluetooth-speaker_041.html

I haven?t checked in here for a while because I thought it was getting boring, but the last few posts are good quality so I guess I?ll add you back to my everyday bloglist. You deserve it my friend 🙂

https://betternewsis.xyz/4-ways-to-accept-credit-cards-directly-to-your-paypal-account/

canadian online drugstore reputable canadian pharmacy or rate canadian pharmacies

http://hipsway.net/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=canadaph.pro canadian pharmacy prices

canadian pharmacies comparison cheap canadian pharmacy online and canadian mail order pharmacy canada drug pharmacy

pharmacy canada online meds no prescription or canadian pharmacy world coupon

http://atcoproperties.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=interpharm.pro rx meds online

buying prescription drugs from canada online canada pharmcy and canadian pharacy canadain pharmacy

Hello, i think that i noticed you visited my site so i got here to ?go back the choose?.I am trying to in finding things to improve my site!I assume its good enough to make use of some of your ideas!!

https://keshetadvisors.com/generate-profits-all-over-which-includes-a-mobile-phone-debit-card-producing-resolution/

drug stores in canada how to buy prescriptions from canada safely or best canadian pharmacy

http://www.adult-web-hosting.net/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=internationalpharmacy.icu canadian drugstore pharmacy

online canadian pharmacies no prescription online pharmacy and canada prescriptions by mail top rated canadian pharmacies

Just wish to say your article is as amazing. The clearness on your post is just cool and i can assume you’re an expert on this subject. Well along with your permission allow me to grab your feed to stay updated with drawing close post. Thanks a million and please keep up the enjoyable work.

https://yousweety.com/products/nude-matte-long-lasting-waterproof-liquid-lipstick-yousweety?pr_prod_strat=copurchase_transfer_learning&pr_rec_id=c86e71f20&pr_rec_pid=6949359845552&pr_ref_pid=7828877312242&pr_seq=uniform

Hello, i think that i saw you visited my website thus i came to ?return the favor?.I am attempting to find things to improve my web site!I suppose its ok to use some of your ideas!!

https://warriorofweb.com/how-to-sell-credit-card-processing-services-from-home/

buy medication online without prescription mexico drug stores online or mexico online pharmacy prescription drugs

http://www.westguardinsurancecompany.biz/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=interpharm.pro canadian mail pharmacy

non prescription online pharmacy canada mail order prescriptions and candadian pharmacy cheap prescription medication online

buying prescription drugs in india mexico drug store online or canada on line pharmacies

http://timeplussystems.info/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=internationalpharmacy.icu online pharmacies without prescriptions

online pharmacy with prescription canadian pharmacy safe and online pharmacy no prescription needed canadian pharmacy

I’ve discovered a treasure trove of knowledge in your blog. Your unwavering dedication to offering trustworthy information is truly commendable. Each visit leaves me more enlightened, and I deeply appreciate your consistent reliability.

https://www.sinkmassage.com/area/seoguipo

online pharmacy no prescriptions canadian pharmacy com or mexican pharmacy

http://panamacitynightlife.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=internationalpharmacy.icu canadian online drug store

saferonlinepharmacy best us online pharmacy and candadian pharmacy canadian discount pharmacy online

canadian-pharmacy top mail order pharmacies or canadian pharamcy

http://scgcement-buildingmaterials.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=internationalpharmacy.icu non prescription canadian pharmacy

no rx meds foreign online pharmacy and buying prescription drugs online without a prescription canadian pharmacy online no prescription

canadian mail order medications meds no prescription or safe canadian pharmacy

http://united-e-way.net/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=interpharm.pro us pharmacy online

buy drugs online without a prescription cheap canadian drugs online and canada pharmacy without prescription biggest online pharmacy

Good post right here. One thing I would like to say is the fact most professional fields consider the Bachelors Degree as the entry level standard for an online certification. Though Associate College diplomas are a great way to start, completing ones Bachelors presents you with many entrance doors to various occupations, there are numerous internet Bachelor Course Programs available from institutions like The University of Phoenix, Intercontinental University Online and Kaplan. Another concern is that many brick and mortar institutions offer Online types of their diplomas but typically for a substantially higher payment than the providers that specialize in online higher education degree plans.

https://www.minoo-cn.com/

Your blog has rapidly become my trusted source of inspiration and knowledge. I genuinely appreciate the effort you invest in crafting each article. Your dedication to delivering high-quality content is apparent, and I eagerly await every new post.

jpgg.com.cn

With havin so much content do you ever run into any issues of plagorism or copyright violation? My website has a lot of exclusive content I’ve either created myself or outsourced but it looks like a lot of it is popping it up all over the web without my authorization. Do you know any ways to help stop content from being ripped off? I’d truly appreciate it.

https://medium.com/@cwina3462/introduction-fortnite-is-a-battle-royale-based-shooter-game-developed-by-epic-games-where-100-f20655611282

Pharmacie en ligne pas cher Pharmacie en ligne fiable or pharmacie ouverte 24/24

http://askdoctorsound.net/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=pharmacieenligne.icu Pharmacie en ligne fiable

pharmacie ouverte Pharmacie en ligne fiable and п»їpharmacie en ligne Pharmacies en ligne certifiГ©es

internet apotheke gГјnstige online apotheke online apotheke preisvergleich

This article is a true game-changer! Your practical tips and well-thought-out suggestions hold incredible value. I’m eagerly anticipating implementing them. Thank you not only for sharing your expertise but also for making it accessible and easy to apply.

http://473.net.cn/

This article resonated with me on a personal level. Your ability to emotionally connect with your audience is truly commendable. Your words are not only informative but also heartwarming. Thank you for sharing your insights.

http://bishan.win/

farmacias online seguras en espaГ±a farmacias online baratas or farmacia online internacional

http://mykeytovegas.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=farmaciabarata.pro farmacias online seguras en espaГ±a

farmacias online baratas farmacias online baratas and farmacia 24h farmacia online madrid

One more important aspect is that if you are a senior citizen, travel insurance regarding pensioners is something you should really take into account. The more mature you are, greater at risk you happen to be for permitting something awful happen to you while in foreign countries. If you are not really covered by a number of comprehensive insurance cover, you could have many serious difficulties. Thanks for sharing your suggestions on this website.

https://blogingpedia.com/how-to-become-a-successful-credit-card-processing-agent-success-guide/

Your blog has rapidly become my trusted source of inspiration and knowledge. I genuinely appreciate the effort you invest in crafting each article. Your dedication to delivering high-quality content is apparent, and I eagerly await every new post.

http://rhdg.cn/

Your unique approach to addressing challenging subjects is like a breath of fresh air. Your articles stand out with their clarity and grace, making them a pure joy to read. Your blog has now become my go-to source for insightful content.

http://677.net.cn/

http://pharmacieenligne.icu/# pharmacie ouverte 24/24

Thanks for your posting. I would also like to say this that the very first thing you will need to conduct is to see if you really need credit score improvement. To do that you will have to get your hands on a copy of your credit file. That should not be difficult, since government necessitates that you are allowed to be issued one totally free copy of the credit report annually. You just have to request the right persons. You can either browse the website for your Federal Trade Commission as well as contact one of the main credit agencies specifically.

https://chai-ai.app/

acquistare farmaci senza ricetta migliori farmacie online 2023 or farmacie online affidabili

http://softsummitaward.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=farmaciaonline.men farmacie online autorizzate elenco

comprare farmaci online con ricetta farmacie online sicure and migliori farmacie online 2023 acquisto farmaci con ricetta

What i don’t realize is actually how you are not actually much more well-liked than you may be right now. You are very intelligent. You realize thus considerably relating to this subject, produced me personally consider it from numerous varied angles. Its like men and women aren’t fascinated unless it is one thing to do with Lady gaga! Your own stuffs outstanding. Always maintain it up!

https://thecrownweb.com/how-to-start-a-payment-processing-company-tips-and-tricks/

This article is a true game-changer! Your practical tips and well-thought-out suggestions hold incredible value. I’m eagerly anticipating implementing them. Thank you not only for sharing your expertise but also for making it accessible and easy to apply.

http://trsq.cn/

http://onlineapotheke.tech/# п»їonline apotheke

Pharmacies en ligne certifiГ©es Pharmacie en ligne livraison gratuite or Pharmacie en ligne livraison 24h

http://schurickdunn.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=edpharmacie.pro Pharmacie en ligne fiable

Pharmacie en ligne sans ordonnance Pharmacie en ligne fiable and Pharmacie en ligne fiable acheter medicament a l etranger sans ordonnance

you are truly a just right webmaster. The website loading pace is incredible. It seems that you’re doing any distinctive trick. Moreover, The contents are masterwork. you have performed a great job on this matter!

https://takkalasi.barrukab.go.id/.-/mawartoto/

I must applaud your talent for simplifying complex topics. Your ability to convey intricate ideas in such a relatable manner is admirable. You’ve made learning enjoyable and accessible for many, and I deeply appreciate that.

http://codehelper.cn/

Heya i?m for the first time here. I found this board and I to find It truly helpful & it helped me out much. I hope to present one thing again and aid others such as you helped me.

https://www.gclubdealer.com/

https://esfarmacia.men/# farmacia online madrid

farmacias online baratas: viagra precio generico – farmacias online seguras en espaГ±a

farmacias online seguras farmacia online madrid or farmacias online seguras en espaГ±a

http://www.homeluxury.net/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=esfarmacia.men farmacias online seguras

farmacias online seguras en espaГ±a farmacia barata and п»їfarmacia online farmacia barata

versandapotheke versandkostenfrei gГјnstige online apotheke or versandapotheke deutschland

http://smartsourceinteractivegroup.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=edapotheke.store online apotheke preisvergleich

internet apotheke п»їonline apotheke and online apotheke preisvergleich internet apotheke

Hello there, You’ve done an incredible job. I?ll certainly digg it and for my part suggest to my friends. I am sure they’ll be benefited from this site.

https://healtheword.xyz/you/21/mawar.html

Your writing style effortlessly draws me in, and I find it nearly impossible to stop reading until I’ve reached the end of your articles. Your ability to make complex subjects engaging is indeed a rare gift. Thank you for sharing your expertise!

http://wdg.asia/

I couldn’t agree more with the insightful points you’ve articulated in this article. Your profound knowledge on the subject is evident, and your unique perspective adds an invaluable dimension to the discourse. This is a must-read for anyone interested in this topic.

http://6554.com.cn/

Your passion and dedication to your craft radiate through every article. Your positive energy is infectious, and it’s evident that you genuinely care about your readers’ experience. Your blog brightens my day!

https://justpaste.it/85sqg

Your blog has rapidly become my trusted source of inspiration and knowledge. I genuinely appreciate the effort you invest in crafting each article. Your dedication to delivering high-quality content is apparent, and I eagerly await every new post.

https://signalmassage.wixsite.com/signalmassage/post/최고의-출장-마사지를-받는-방법에-대한-팁

Your enthusiasm for the subject matter shines through every word of this article; it’s infectious! Your commitment to delivering valuable insights is greatly valued, and I eagerly anticipate more of your captivating content. Keep up the exceptional work!

http://761.net.cn/

Your blog is a true gem in the vast expanse of the online world. Your consistent delivery of high-quality content is truly commendable. Thank you for consistently going above and beyond in providing valuable insights. Keep up the fantastic work!

http://hougua.cn/

http://edapotheke.store/# online-apotheken

farmacias online seguras: kamagra precio en farmacias – farmacia envГos internacionales

п»їfarmacia online migliore farmacie online affidabili or comprare farmaci online all’estero

http://all-that-jazzbrands.us/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=itfarmacia.pro farmacia online piГ№ conveniente

farmacie online sicure migliori farmacie online 2023 and acquisto farmaci con ricetta farmaci senza ricetta elenco

I wanted to take a moment to express my gratitude for the wealth of invaluable information you consistently provide in your articles. Your blog has become my go-to resource, and I consistently emerge with new knowledge and fresh perspectives. I’m eagerly looking forward to continuing my learning journey through your future posts.

http://xcxcc.cn/

I wanted to take a moment to express my gratitude for the wealth of valuable information you provide in your articles. Your blog has become a go-to resource for me, and I always come away with new knowledge and fresh perspectives. I’m excited to continue learning from your future posts.

https://myspace.com/danbammassage/post/activity_profile_7392391_e684cddee91f4a38a3249031d0d72ab0/

I’m continually impressed by your ability to dive deep into subjects with grace and clarity. Your articles are both informative and enjoyable to read, a rare combination. Your blog is a valuable resource, and I’m grateful for it.

https://diigo.com/0tzvc0

Thank you for the sensible critique. Me and my neighbor were just preparing to do a little research about this. We got a grab a book from our local library but I think I learned more clear from this post. I’m very glad to see such fantastic info being shared freely out there.

https://lipstickaddict.com/the-ultimate-guide-to-mastering-merchant-services-2/

In a world where trustworthy information is more crucial than ever, your dedication to research and the provision of reliable content is truly commendable. Your commitment to accuracy and transparency shines through in every post. Thank you for being a beacon of reliability in the online realm.

http://0679.com.cn/

I want to express my sincere appreciation for this enlightening article. Your unique perspective and well-researched content bring a fresh depth to the subject matter. It’s evident that you’ve invested considerable thought into this, and your ability to convey complex ideas in such a clear and understandable way is truly commendable. Thank you for generously sharing your knowledge and making the learning process enjoyable.

https://theomnibuzz.com/ec84acec9d98-ed99a9ed9980ed95a8ec9d84-eba78ceb81bded9598eb9dbc-eca09ceca3bcecb69cec9ea5eba788ec82aceca780ec9980-eca09ceca3bcecb69c/

In a world where trustworthy information is more crucial than ever, your dedication to research and the provision of reliable content is truly commendable. Your commitment to accuracy and transparency shines through in every post. Thank you for being a beacon of reliability in the online realm.

https://twitter.com/dajokoshop/status/1706547546573959494

Online medicine home delivery best online pharmacy india or top online pharmacy india

http://perma-casting.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=indiapharm.cheap buy prescription drugs from india

indian pharmacy online indian pharmacy online and best india pharmacy indianpharmacy com

Simply desire to say your article is as surprising. The clarity in your post is simply nice and i can assume you are an expert on this subject. Fine with your permission let me to grab your RSS feed to keep up to date with forthcoming post. Thanks a million and please carry on the enjoyable work.

https://purwell.com/

I can’t help but be impressed by the way you break down complex concepts into easy-to-digest information. Your writing style is not only informative but also engaging, which makes the learning experience enjoyable and memorable. It’s evident that you have a passion for sharing your knowledge, and I’m grateful for that.

https://twitter.com/dajokoshop/status/1706545503603937427

This article is a true game-changer! Your practical tips and well-thought-out suggestions hold incredible value. I’m eagerly anticipating implementing them. Thank you not only for sharing your expertise but also for making it accessible and easy to apply.

http://1540.com.cn/

I couldn’t agree more with the insightful points you’ve articulated in this article. Your profound knowledge on the subject is evident, and your unique perspective adds an invaluable dimension to the discourse. This is a must-read for anyone interested in this topic.

https://www.xaphyr.com/blogs/485755/ED8F89EC98A8EC9D84-EBB09CEAB2ACED9598EB8BA4-ECB0BDEC9B90ECB69CEC9EA5EBA788EC82ACECA780EC9980-ECB0BDEC9B90ECB69CEC9EA5EC9588EBA788EC9D98-EAB681EAB7B9ECA081EC9DB8-EC9588EB82B4EC849C

canadian pharmacy prices: canadian pharmacy india – canadian pharmacy ratings

buying from online mexican pharmacy best online pharmacies in mexico or mexico pharmacies prescription drugs

http://lupusmonth.mobi/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=mexicopharm.store buying prescription drugs in mexico

mexican pharmaceuticals online buying from online mexican pharmacy and mexican pharmaceuticals online mexican rx online

https://businessvoicenow.com/?p=22051

https://onlinehoki.pro/mawartoto/

A pharmacy that breaks down international barriers. buy prescription drugs from india: india pharmacy mail order – india online pharmacy

mail order pharmacy india: Online medicine order – top 10 online pharmacy in india

canadian pharmacy king reviews northwest pharmacy canada or best online canadian pharmacy

http://ultraburndiet.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=canadapharm.store www canadianonlinepharmacy

canadian pharmacies online cheap canadian pharmacy and best canadian pharmacy online canadian pharmacy online

One more thing to say is that an online business administration study course is designed for individuals to be able to without problems proceed to bachelor degree education. The Ninety credit diploma meets the other bachelor education requirements and once you earn your associate of arts in BA online, you will possess access to up to date technologies within this field. Several reasons why students want to get their associate degree in business is because they can be interested in this area and want to have the general education necessary in advance of jumping into a bachelor education program. Thanks for the tips you provide with your blog.

https://www.hotpartystripper.com/miami-strippers.htm

Your writing style effortlessly draws me in, and I find it nearly impossible to stop reading until I’ve reached the end of your articles. Your ability to make complex subjects engaging is indeed a rare gift. Thank you for sharing your expertise!

http://chezou.cn/

Your storytelling prowess is nothing short of extraordinary. Reading this article felt like embarking on an adventure of its own. The vivid descriptions and engaging narrative transported me, and I eagerly await to see where your next story takes us. Thank you for sharing your experiences in such a captivating manner.

https://www.instagram.com/p/Cxpi55TvB-T/

Your positivity and enthusiasm are undeniably contagious! This article brightened my day and left me feeling inspired. Thank you for sharing your uplifting message and spreading positivity among your readers.

https://twitter.com/sevenmassageko/status/1706532940975661385

Hello, I think your site might be having browser compatibility issues. When I look at your website in Firefox, it looks fine but when opening in Internet Explorer, it has some overlapping. I just wanted to give you a quick heads up! Other then that, terrific blog!

https://caymandesigngroup.com/

mail order pharmacy india world pharmacy india or india pharmacy

http://miconcms.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=indiapharm.cheap online pharmacy india

indian pharmacy online pharmacy india and best online pharmacy india reputable indian pharmacies

canadian pharmacy price checker is canadian pharmacy legit or canada cloud pharmacy

http://ironwoodranch.net/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=canadapharm.store canadapharmacyonline com

canadian drug prices canadian drugs pharmacy and canadian pharmacy online reviews best mail order pharmacy canada

Their medication therapy management is top-notch. canadian family pharmacy: canadian pharmacy ratings – canadian pharmacy online ship to usa

best canadian online pharmacy: my canadian pharmacy – canada drugstore pharmacy rx

indian pharmacy paypal: best online pharmacy india – india pharmacy mail order

Ahaa, itts good dialogue on thee topic off

this artgicle aat this place aat this webb site, I hve read all that, so att this tie mee

aso commenting at this place.

my sife … 6413

I can’t express how much I value the effort the author has put into creating this outstanding piece of content. The clarity of the writing, the depth of analysis, and the wealth of information offered are simply astonishing. His enthusiasm for the subject is apparent, and it has definitely struck a chord with me. Thank you, author, for sharing your insights and enhancing our lives with this exceptional article!

https://zfb590.com/2023/09/25/7-items-you-must-know-concerning-bank-card-running-computer-software/

Your storytelling prowess is nothing short of extraordinary. Reading this article felt like embarking on an adventure of its own. The vivid descriptions and engaging narrative transported me, and I eagerly await to see where your next story takes us. Thank you for sharing your experiences in such a captivating manner.

http://3549.com.cn/

I want to express my sincere appreciation for this enlightening article. Your unique perspective and well-researched content bring a fresh depth to the subject matter. It’s evident that you’ve invested considerable thought into this, and your ability to convey complex ideas in such a clear and understandable way is truly commendable. Thank you for generously sharing your knowledge and making the learning process enjoyable.

https://www.pinterest.co.kr/pin/875950196257906011

I’m genuinely impressed by how effortlessly you distill intricate concepts into easily digestible information. Your writing style not only imparts knowledge but also engages the reader, making the learning experience both enjoyable and memorable. Your passion for sharing your expertise is unmistakable, and for that, I am deeply appreciative.

https://pin.it/5IEMo3L

It’s genuinely very clmplicated in thiis busy lfe

too listen news onn TV, sso I jusat use weeb foor that purpose, and take

the mst recent news.

Allso visitt mmy web page 9987

purple pharmacy mexico price list mexico drug stores pharmacies or medication from mexico pharmacy

http://www.fileconductor.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=mexicopharm.store/ buying prescription drugs in mexico

mexican border pharmacies shipping to usa purple pharmacy mexico price list and medicine in mexico pharmacies reputable mexican pharmacies online

They consistently go above and beyond for their customers. purple pharmacy mexico price list: purple pharmacy mexico price list – buying from online mexican pharmacy

http://dokobo.ru/kct-triumphofthewill.info-uis.xml

I have noticed that over the course of constructing a relationship with real estate owners, you’ll be able to come to understand that, in every single real estate contract, a percentage is paid. Finally, FSBO sellers do not “save” the payment. Rather, they fight to earn the commission by doing a great agent’s work. In this, they commit their money as well as time to complete, as best they can, the obligations of an broker. Those assignments include uncovering the home through marketing, delivering the home to buyers, constructing a sense of buyer desperation in order to trigger an offer, arranging home inspections, taking on qualification inspections with the loan company, supervising fixes, and facilitating the closing.

https://orienteweb.com/how-to-choose-the-best-online-payment-platform-for-your-business/

buy prescription drugs from canada cheap canadian pharmacy near me or canada drugstore pharmacy rx

http://cozabedding.info/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=canadapharm.store canadian pharmacy 24 com

best canadian pharmacy pharmacy wholesalers canada and canadian mail order pharmacy maple leaf pharmacy in canada

http://dokobo.ru/mjc-triumphofthewill.info-zix.xml

canada ed drugs: adderall canadian pharmacy – pet meds without vet prescription canada

http://dokobo.ru/jur-triumphofthewill.info-sxt.xml

http://dokobo.ru/xxx-triumphofthewill.info-ptc.xml

zithromax prescription in canada azithromycin 500 mg buy online zithromax for sale usa

Your storytelling abilities are nothing short of incredible. Reading this article felt like embarking on an adventure of its own. The vivid descriptions and engaging narrative transported me, and I can’t wait to see where your next story takes us. Thank you for sharing your experiences in such a captivating way.

http://xslt.win/

I must applaud your talent for simplifying complex topics. Your ability to convey intricate ideas in such a relatable manner is admirable. You’ve made learning enjoyable and accessible for many, and I deeply appreciate that.

https://justpaste.it/abdvu

Their 24/7 support line is super helpful. http://edpillsotc.store/# medicine for impotence

doxycycline price uk doxycycline 50 mg coupon or where can i buy doxycycline capsules

http://911dayofservice.net/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=doxycyclineotc.store doxycycline 40 mg coupon

doxycycline 50 mg price doxycycline 200 mg pill and doxycycline brand doxycycline price

Unrivaled in the sphere of international pharmacy. https://doxycyclineotc.store/# medicine doxycycline 100mg

best medication for ed ed pills non prescription ed pills that work

The staff exudes professionalism and care. erection pills online: Over the counter ED pills – the best ed pills

I couldn’t agree more with the insightful points you’ve articulated in this article. Your profound knowledge on the subject is evident, and your unique perspective adds an invaluable dimension to the discourse. This is a must-read for anyone interested in this topic.

https://notes.io/qWcMe

cheap erectile dysfunction pill ed drugs list or pills erectile dysfunction

http://meubles-decoration.atylia.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=edpillsotc.store ed medications

erectile dysfunction drugs ed meds and п»їerectile dysfunction medication best male enhancement pills

The best place for health consultations. http://azithromycinotc.store/# zithromax online usa

In a world where trustworthy information is more crucial than ever, your dedication to research and the provision of reliable content is truly commendable. Your commitment to accuracy and transparency shines through in every post. Thank you for being a beacon of reliability in the online realm.

http://jstf.com.cn/

Your positivity and enthusiasm are undeniably contagious! This article brightened my day and left me feeling inspired. Thank you for sharing your uplifting message and spreading positivity among your readers.

https://www.instagram.com/p/CxpY1PeL2iY/

I’d like to express my heartfelt appreciation for this insightful article. Your unique perspective and well-researched content bring a fresh depth to the subject matter. It’s evident that you’ve invested considerable thought into this, and your ability to convey complex ideas in such a clear and understandable way is truly commendable. Thank you for sharing your knowledge so generously and making the learning process enjoyable.

https://www.instagram.com/p/CxpWwwiLDjn/

https://edpillsotc.store/# erectile dysfunction medications

Your dedication to sharing knowledge is unmistakable, and your writing style is captivating. Your articles are a pleasure to read, and I consistently come away feeling enriched. Thank you for being a dependable source of inspiration and information.

https://open-isa.org/members/songum0/activity/660805/

Your passion and dedication to your craft radiate through every article. Your positive energy is infectious, and it’s evident that you genuinely care about your readers’ experience. Your blog brightens my day!

https://rentry.co/txux3

Things i have observed in terms of pc memory is that there are requirements such as SDRAM, DDR or anything else, that must match the features of the mother board. If the personal computer’s motherboard is reasonably current while there are no operating system issues, improving the ram literally normally requires under one hour. It’s one of many easiest laptop or computer upgrade techniques one can consider. Thanks for spreading your ideas.

https://170.64.181.52/

I must applaud your talent for simplifying complex topics. Your ability to convey intricate ideas in such a relatable manner is admirable. You’ve made learning enjoyable and accessible for many, and I deeply appreciate that.

https://dajokoshop.wixsite.com/dajokoshop/post/EBB094EB9494-EBA788EC82ACECA780-EAB1B4EAB095ED959C-EC82B6EC9D84-ED96A5ED959C-EB9FADEC8594EBA6ACED959C-EBB0A9EBB295

I wanted to take a moment to express my gratitude for the wealth of invaluable information you consistently provide in your articles. Your blog has become my go-to resource, and I consistently emerge with new knowledge and fresh perspectives. I’m eagerly looking forward to continuing my learning journey through your future posts.

http://4655.com.cn/

I wish to express my deep gratitude for this enlightening article. Your distinct perspective and meticulously researched content bring fresh depth to the subject matter. It’s evident that you’ve invested a significant amount of thought into this, and your ability to convey complex ideas in such a clear and understandable manner is truly praiseworthy. Thank you for generously sharing your knowledge and making the learning process so enjoyable.

https://diigo.com/0tzah9