The idea of using gas to kill, disable or harass, the enemy was first proposed during the Crimean War.

At the siege of Sebastopol, in 1855, a young naval officer, devised a plan to burn five hundred tons of sulphur in order to produce a gas that would suffocate the Russians.

The British government rejected his idea, both on grounds of its inhumanity and because they believed it contravened the laws of civilised warfare. This opinion was later formally endorsed by The Hague Convention of 1907.

Germany Takes the Lead

Germany’s lead in gas warfare was the result of their superior manufacturing capacity of the industrial dyes on which gas-warfare is based.

Great German chemical works such as the Badische Anilin und Sodafabrik at Ludwigshafen, the Bayer Company at Leverkusen and the Griesheim-Elektron Chemische Fabrik possessed matchless research and development facilities which could quickly and easily be adapted to satisfy military demands.

The Role of Fritz Haber

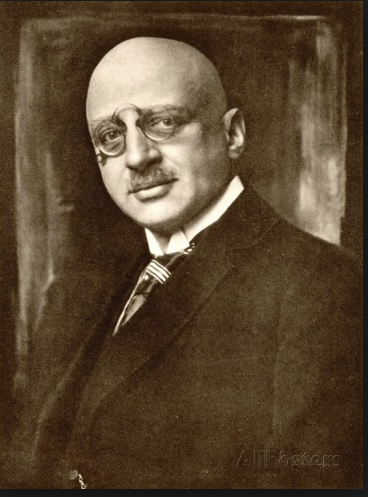

Research into the military use of gas was conducted by Fritz Haber, a Jewish chemist, employed by Berlin’s Kaiser Wilhelm Institute. Haber was awarded the Nobel Prize for chemistry in 1918.

Fritz Haber ‘father of Gas Warfare’

Despite an explosion in mid-December 1914, which killed his assistant Dr Otto Sackur, Haber continued his increasingly successful work.

The First Gas Attacks

This enabled the German’s to launch their first chlorine gas attack, against the Russians on the Eastern Front, in early 1915. The attack failed due to adverse weather conditions which neutralised the gas’s effects.

Undeterred, they tried again in the spring of the same year, using chlorine gas against French troops at Ypres.

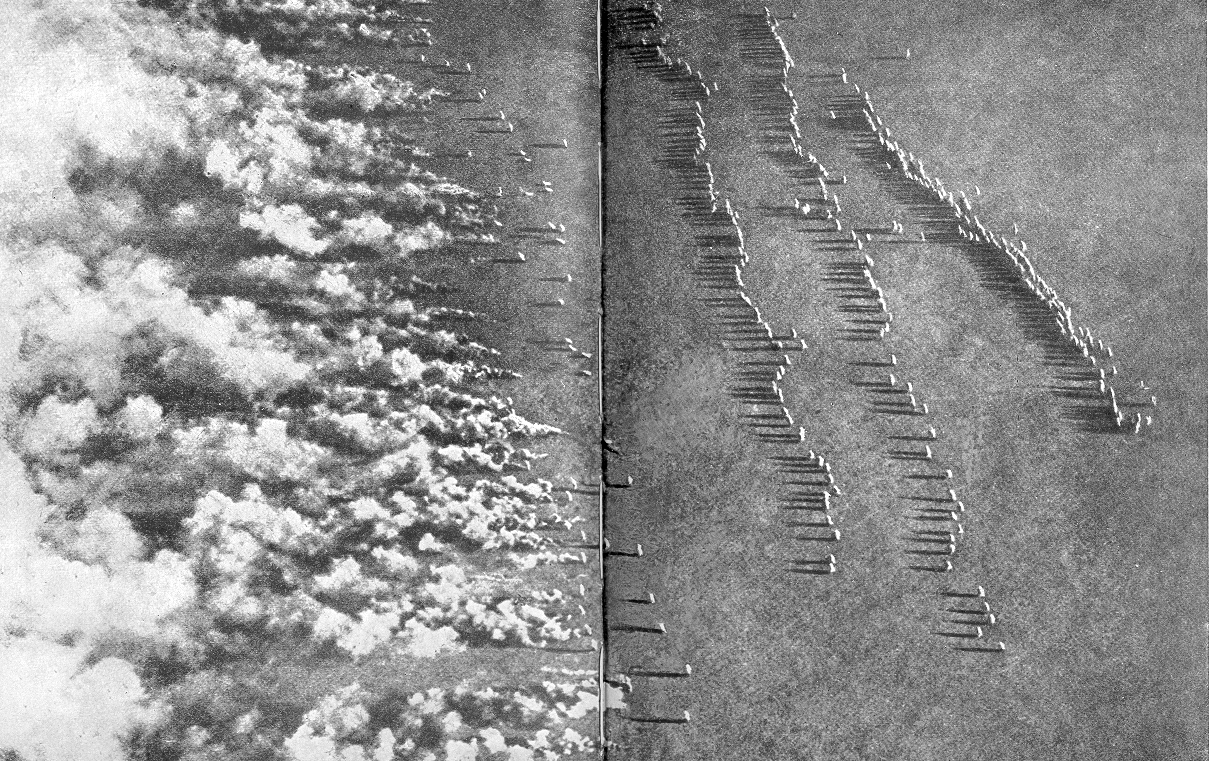

Troops advance towards clouds of poison gas

Deadly Clouds

At 5.30 pm on April 22nd, 1915, soldiers to the north of Ypres noticed two curious greenish yellow clouds on the ground on either side of the German line.

The clouds spread laterally, joined up, and, moving before a light wind, became a bluish white mist, such as is seen over water meadows on a frosty night.

Wafted by the breeze, the cloud drifted lazily along the ground and, moments later, flooded over and into the enemy trenches with horrific consequences. One observer noted how: ‘Choking, coughing, retching, gasping for breath, and half blinded…the troops were seized with terror at the enemy’s expedient and gave ground, stumbling back through heavy shell fire in their efforts to find some escape from the deadly fumes.’

This attack claimed more than 65,000 casualties.

Victims of Torture and Death

Gas attacks tended to be made at night or in the early hours of the morning when atmospheric conditions were most suitable and the darkness and confusion made it far harder for troops to know when the assault had started.

As a result, the psychological impact produced by fear and uncertainty soon became almost as debilitating as the gas itself. Indeed, as the war progressed gas, which had initially been proposed either as a means of enabling breakthroughs or in retaliation, was being advocated on other grounds as well.

Not only were its victims incapacitated, fighting efficiency was significantly diminished as troops panicked, morale broken and the enemy’s willingness to fight destroyed.

‘In the face of gas, without protection, individuality was annihilated,’ comments historian Charles, Robert Cruttwell, ‘the soldier in the trench became a mere passive recipient of torture and death.’

The Allies Race to Catch Up

Once Germany had demonstrated the lethal potency and military advantages of gas warfare, their enemies raced to catch-up.

In 1914, the British, who had neglected their synthetic-dye industry, possessed little or no commercial expertise in producing organic poisons. Within a year of the attack at Ypres, however, they constructed a new laboratory specialising in chemical warfare at Porton Down in the south-west of England. Its location was, reportedly, chosen due to the surrounding countryside’s similarity to the ridges east of Ypres.

The Gases Used

Chemists developed two forms of tear gas – benzyl bromide and xylyl bromide – and nine lung irritants, including chlorine and phosgene. They also developed paralysing gases, such as hydrocyanic acid and sulphuretted hydrogen, which acted directly on the nervous system to cause death within seconds.

There were ‘Sternutators’, so called because they induced sneezing (sternutation is its medical name), as well as an intense burning and aching pain in the eyes, nose, throat and chest, accompanied by nausea and great depression.

Finally, there was Mustard Gas, whose nature and effects I will describe in a moment.

Colour Coded Poisons

The Allies identified different types of gas by means of coloured stars.

Red stars indicated chlorine and yellow stars a mixture comprising 70 percent chlorine and 30 percent chloropicrin. This combination had the dual advantages of being even more immediately incapacitating and potentially lethal.

The most widely used were White Star gasses. A powerful lung irritant they were made up of 50 percent chlorine and 50 percent phosgene.

By the middle of 1916, White Star had become what Major General C.H. Foulkes, commander of the Royal Engineers’ Special Gas Brigade, called ‘the workhorse gas.’

Mustard Gas

A latecomer to the battlefield, ßß-dichlor-ethyl-sulphide was a vesicant (one causing blistering) whose properties had first been described by Victor Meyer in 1886.

The Germans referred to it as Yellow-Cross, from the yellow double-cross or Lorraine-cross markings used to identify these shells.

The French knew it as Yperite because it was first used by the Germans at Ypres.

The British called it either BB gas, from the first two Greek letters of its chemical name, or more informally HS (Hun Stuff).

It was best known, however, as Mustard Gas because of its faint odour reminiscent of either mustard or garlic, depending on its impurities.

The Medical Effects of Mustard Gas

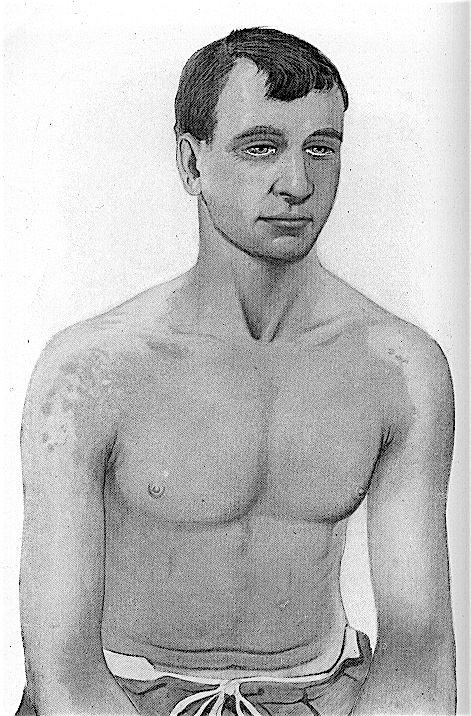

The gas burns any part of the body it touches. Especially vulnerable are the face and hands which, typically, are unprotected by clothing. Moist regions, such as armpits, groin, genitalia and inner thighs, are also at high risk because they are moist.

The horrendous nature of these injuries is graphically described in the Official History of the Great War: ‘The most important pathological changes to be found in the human body, after exposure to mustard gas, are those in the respiratory tract,’ it notes. ‘The destruction of the membrane may have proceeded to such an extent that the whole area of the trachea and the larger bronchi are covered by a loosely adhered false membrane or slough of a yellow colour several millimetres thick.

Occasionally the slough on the trachea and larger bronchi can be separated as a whole and removed giving the appearance of a cast of the bronchial tree. Such a cast has been coughed up during life… The skin exhibits all stages of burn from the primary erythema, which is the first manifestation of the cutaneous irritation, up to the final stage of deep burn with necrosis and sloughing of tissues.

The eyes share in the general inflammation of the skin, and exhibit all the stages of an acute conjunctivitis, from the early chemosis up to an ulcerative keratitis.’

Illustration from a WW1 medical textbook showing some of the effects of Mustard Gas

Mustard Gas’s Unique Properties

A key feature of mustard-gas poisoning, and the one that sets it apart from other battlefield gases, is the slow rate at which its effects develop.

‘Only a few of the men who were gassed died at once,’ one Front Line doctor wrote. ‘Many of the men felt perfectly well after the bombardment [and] marched back with their companions on relief, under the impression that they had got through the affair satisfactorily. Several hours elapsed before they reported sick.’

The fatal course of the delayed illness was particularly striking between two and forty-eight hours after exposure, as symptoms gradually intensified.

A Gas That Keeps on Giving

A liquid at room temperature, mustard gas’s high boiling makes it extremely persistent.

An area would remain dangerous for hours or even days as the poisonous fluid either slowly evaporated or was broken down by the elements.

In April 1918, it was used so extensively during the shelling of Armentieres that the gutters ran with it and no German troops were permitted to enter the town for two weeks.

A Terrifying New Experience

Mustard gas was completely unlike any other that Allied soldiers ever experienced.

Until then they had associated ‘gas’ with violent irritating or choking sensations.

The gas mask used by French troops in WW1

Many, under the false impression it was not strong enough to hurt them, omitted to wear their gas masks or to keep them on for long enough. Nor did they initially appreciate that ground in the vicinity of a gas shell burst was heavily contaminated by the poison and continued to be a source of danger long after the bombardment had ceased.

The British Use the Gas

Although UK researchers had first tested Mustard gas in the summer of 1916 and while the Commander-in-Chief, Sir Douglas Haig, had been eager to employ it the British government initially refused to sanction its use.

On the basis of the injuries it had produced in laboratory animals, Lloyd George and his ministers regarded the gas as far too barbaric to employ.

The German military, free from the control of their civilian leaders, had no such scruples.

They deployed the gas, for the first time, at Ypres on the night of July 12th-13th 1917, fourteen months ahead of it becoming generally available to British troops.

Once they did start, however, Mustard gas rapidly became used widely, frequently and enthusiastically.

German infantry advance through clouds of gas on the Western Front 1918

Between 1st October 1918 and the end of the war, on November 11th Mustard gas attacks led to an estimated twelve thousand German casualties.

The Battle of Courtrai

On 13th October, the day before the start of what would become known as the Battle of Courtrai, the intelligence officer of the 6th Brigade Royal Garrison Artillery noted in his diary: ‘At 7.30 p.m. we carried out a gas concentration . . . mustard gas shells were used for the first time.’

Before dawn the following morning, German front-line troops heard the unmistakable sounds of British soldiers assembling for an attack, and requested an artillery bombardment of the British lines.

Although this was carried out, the German gunners, firing blind in the darkness. could only lay down their barrage on positions identified by observers the previous day.

The British, who had noted the fall of shells, and had evacuated the areas concerned, suffered few casualties among the assembling troops.

At 5.30 am, on what promised to be a sunny morning, soldiers from the 90th and 21st Infantry Brigades swarmed from their trenches and advanced through the early morning mist, along a 3,500-yard front, towards the river Lys.

With no cover, in the featureless valley floor basin, the artillery barrage that started exactly three minutes before jumping off time, was of vital importance.

The official historian of the 30th Division noted: ‘It was, for the division, the last big barrage of the war…. (It) was as good as any under which the division had advanced. It came down along and in front and behind the Lys with all the cumulative fury of four years of war – machine gun bullets, shrapnel, smoke, gas, thermite and high explosive – the smoke shells from the field guns were particularly blessed by the infantry advancing as close as they could to the curtain they made, for save on the extreme left where it was thinnest, it hid them from what defensive fire the enemy was able to bring to bear.’

Germans Surrender

With an already demoralised enemy no longer prepared to sacrifice themselves, for what they now realised was a lost cause, the British troops rapidly gained ground.

In the first few hours hundreds of Germans, including one officer who arrived fully prepared for captivity with a packed lunch and his servant, surrendered.

At the same time, scores of injured German troops, many blinded by gas, slowly made their way to Front Line aid stations.

German nurses treating gas injured soldiers on the Western Front

Among them was a soldier destined to become the most famous and most notorious of the war.

Lance-corporal Adolf Hitler.

In my next blog I will be describing the controversial medical nature and terrible political consequences of his injuries.

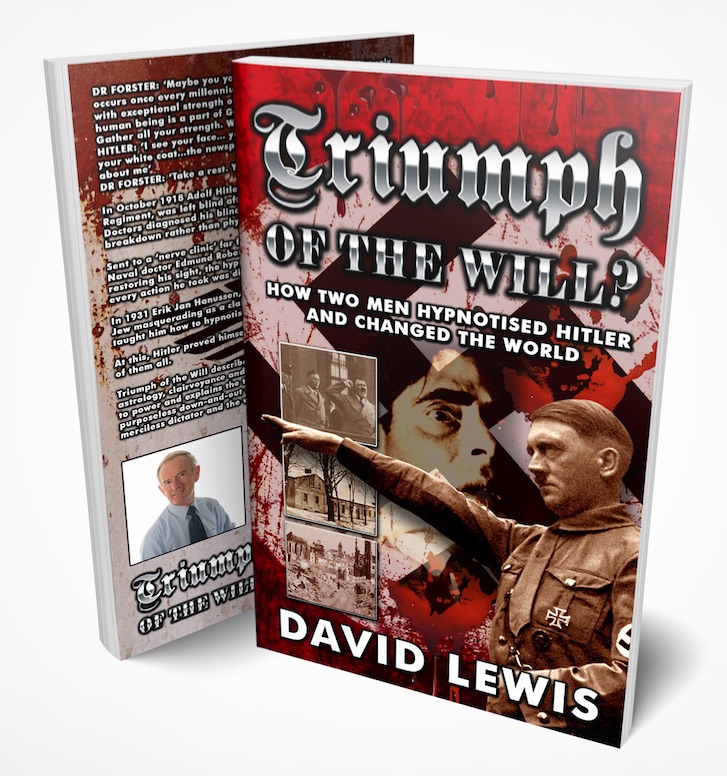

For further details of the Battle of Courtrai and the gassing of Hitler, see my new book Triumph of the Will?

3505 Comments. Leave new

Great post. http://www.bezogoroda.ru

Howdy I am so glad I found your site, I really found you by mistake, while I was researching on Bing for something else, Anyhow I am here now and would just like to say thanks a lot for a fantastic post and a all round enjoyable blog (I also love the theme/design), I dont have time to go through it all at the minute but I have saved it and also included your RSS feeds, so when I have time I will be back to read much more, Please do keep up the excellent jo. аренда офиса в минском районе

I seriously love your blog.. Very nice colors & theme. Did you make this web site yourself? Please reply back as I’m looking to create my own blog and want to learn where you got this from or what the theme is called. Many thanks! Jurist

Pretty section of content. I just stumbled upon your web site and in accession capital to assert that I acquire in fact enjoyed account your blog posts. Any way I’ll be subscribing to your augment and even I achievement you access consistently rapidly. Jurist

Hi, I think your site might be having browser compatibility issues. When I look at your blog in Safari, it looks fine but when opening in Internet Explorer, it has some overlapping. I just wanted to give you a quick heads up! Other then that, wonderful blog!

https://e-almet.ru/forum/thread-823/

Hi there i am kavin, its my first time to commenting anywhere, when i read this article i thought i could also make comment due to this brilliant article. аренда ричтрака в минске

This information is priceless. When can I find out more? Это сообщение отправлено с сайта GoToTop.ee

https://itoboz.com/news/sovremennye-instrumenty-seo-prodvizheniya-finansovyx-sajtov/

Saved as a favorite, I really like your website!

https://gameonline20.ru/category/obzor-igr/

This is really interesting, You are a very skilled blogger. I’ve joined your feed and look forward to seeking more of your great post. Also, I have shared your site in my social networks!

https://линуксминт.рф/users/729

Unquestionably consider that that you stated. Your favourite justification appeared to be at the net the simplest thing to be aware of. I say to you, I definitely get irked whilst folks consider concerns that they plainly do not understand about. You controlled to hit the nail upon the top as welland also defined out the whole thing with no need side effect , folks can take a signal. Will likely be back to get more. Thank you smartremstroy.ru

Hello my family member! I want to say that this post is amazing, nice written and come with approximately all significant infos. I’d like to look more posts like this . Это сообщение отправлено с сайта https://ru.gototop.ee/

https://gid.volga.news/661903/article/doski-obyavlenij-novyj-vitok-razvitiya-v-cifrovom-mire.html

Conclusion: CandyMail.org stands out as a leading platform for individuals seeking an anonymous and secure email service. With its user-friendly interface, robust privacy measures, and disposable email addresses, CandyMail.org provides a reliable solution to protect users’ identities and confidential information. As the need for online privacy continues to grow, CandyMail.org remains at the forefront, empowering individuals to communicate securely in an increasingly connected world.

https://candymail.org/ru/

dating website free: online dating best sites free – ourtime dating site

prednisone rx coupon: https://prednisone1st.store/# fast shipping prednisone

buying propecia without insurance propecia tablets

can i order mobic without rx: can i get generic mobic no prescription – where buy cheap mobic without rx

Thanks for the blog post.Much thanks again. Cool.

https://www.fiverr.com/uptotop

Drug information.

how much is amoxicillin amoxicillin for sale online – amoxicillin price without insurance

Top 100 Searched Drugs.

Fantastic blog.Really thank you! Will read on…

mobileautodetailingkc.com

https://mobic.store/# how to get generic mobic without insurance

cost of cheap propecia pill order generic propecia price

impotence pills top ed pills ed medications online

can i get cheap mobic without dr prescription: where can i get generic mobic online – where can i buy generic mobic online

cost of generic mobic for sale: generic mobic pills – Homepage

https://pharmacyreview.best/# trustworthy canadian pharmacy

canadian pharmacy pharmacy wholesalers canada

buy generic propecia buying generic propecia without insurance

https://pharmacyreview.best/# canadian neighbor pharmacy

Some are medicines that help people when doctors prescribe.

generic amoxicillin amoxicillin medicine – buy amoxicillin without prescription

Top 100 Searched Drugs.

generic amoxicillin cost amoxicillin 500mg without prescription – amoxicillin 500 capsule

canadapharmacyonline best canadian pharmacy online

men’s ed pills: best ed pills at gnc – natural ed medications

canada drugs online reviews canadian pharmacy online store

ed treatment review male erection pills ed medication

buy cheap amoxicillin online where can i buy amoxicillin over the counter uk – amoxicillin 500 tablet

ed drug prices: ed medication – erectile dysfunction medicines

http://cheapestedpills.com/# ed meds online

https://mobic.store/# where buy cheap mobic for sale

Read information now.

propecia pills buy generic propecia prices

Long-Term Effects.

cost of propecia price get generic propecia pill

get mobic tablets how can i get mobic without insurance cost of generic mobic no prescription

amoxil pharmacy amoxicillin for sale online – amoxicillin no prescription

buy cheap amoxicillin online: amoxicillin order online no prescription medicine amoxicillin 500mg

canadian pharmacy prices canadian online pharmacy

how to get cheap mobic no prescription: how to get mobic online – buying cheap mobic without prescription

http://mexpharmacy.sbs/# mexican online pharmacies prescription drugs

ordering drugs from canada legit canadian online pharmacy or canadian pharmacy victoza

http://yamst.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=certifiedcanadapharm.store canadian pharmacy meds reviews

canadian drugstore online safe canadian pharmacies and canada rx pharmacy canadian pharmacy 24h com

canadian drug: best canadian pharmacy online – canada pharmacy online

top online pharmacy india top online pharmacy india or top 10 pharmacies in india

http://imageneration.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=indiamedicine.world buy medicines online in india

indianpharmacy com п»їlegitimate online pharmacies india and mail order pharmacy india buy medicines online in india

canadian neighbor pharmacy: precription drugs from canada – canadian drugs online

mexico drug stores pharmacies: mexican rx online – mexico drug stores pharmacies

https://mexpharmacy.sbs/# buying from online mexican pharmacy

mexican border pharmacies shipping to usa pharmacies in mexico that ship to usa or medicine in mexico pharmacies

http://slimatee.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=mexpharmacy.sbs buying prescription drugs in mexico online

purple pharmacy mexico price list buying prescription drugs in mexico online and mexico drug stores pharmacies buying prescription drugs in mexico

mexico drug stores pharmacies: mexican pharmaceuticals online – mexican mail order pharmacies

https://indiamedicine.world/# top 10 online pharmacy in india

http://indiamedicine.world/# cheapest online pharmacy india

indianpharmacy com buy medicines online in india or india online pharmacy

http://levihncoon.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=indiamedicine.world top 10 online pharmacy in india

buy prescription drugs from india best online pharmacy india and online pharmacy india best india pharmacy

online pharmacy india: top 10 online pharmacy in india – reputable indian online pharmacy

best mail order pharmacy canada certified canadian international pharmacy or canada discount pharmacy

http://european-cheese.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=certifiedcanadapharm.store canadian pharmacy

canadian pharmacy checker canada drugs online and canadian pharmacy phone number canadian pharmacy reviews

buy prescription drugs from india: cheapest online pharmacy india – pharmacy website india

top 10 online pharmacy in india indian pharmacies safe or top 10 online pharmacy in india

http://fumpa.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=indiamedicine.world indian pharmacy online

best online pharmacy india reputable indian online pharmacy and reputable indian pharmacies buy prescription drugs from india

https://indiamedicine.world/# Online medicine order

mexican online pharmacies prescription drugs: mexico drug stores pharmacies – mexican mail order pharmacies

https://certifiedcanadapharm.store/# canadian family pharmacy

mexican drugstore online medicine in mexico pharmacies or п»їbest mexican online pharmacies

http://executiveforce.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=mexpharmacy.sbs buying prescription drugs in mexico

medicine in mexico pharmacies mexican drugstore online and mexico drug stores pharmacies best online pharmacies in mexico

canadapharmacyonline: canada drugs online review – canadian pharmacy near me

online shopping pharmacy india india pharmacy mail order or best online pharmacy india

http://www.securepacificcorp.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=indiamedicine.world online pharmacy india

india pharmacy mail order canadian pharmacy india and buy medicines online in india india online pharmacy

https://indiamedicine.world/# india pharmacy

canadian mail order pharmacy: canadian pharmacy victoza – canadian drugs online

canada cloud pharmacy pet meds without vet prescription canada or is canadian pharmacy legit

http://raycatenabridgewater.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=certifiedcanadapharm.store thecanadianpharmacy

canadian pharmacy uk delivery best canadian pharmacy to buy from and canadian pharmacy meds adderall canadian pharmacy

canadian pharmacy meds: canadian drug pharmacy – canadian drugstore online

buy prescription drugs from india top online pharmacy india or india pharmacy

http://designs4outdoorliving.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=indiamedicine.world world pharmacy india

indianpharmacy com pharmacy website india and best online pharmacy india indian pharmacy

https://certifiedcanadapharm.store/# canadian pharmacy world

http://indiamedicine.world/# buy prescription drugs from india

mexican border pharmacies shipping to usa mexican online pharmacies prescription drugs or mexico drug stores pharmacies

http://upstotaltrack.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=mexpharmacy.sbs pharmacies in mexico that ship to usa

reputable mexican pharmacies online buying prescription drugs in mexico and mexico pharmacies prescription drugs medicine in mexico pharmacies

mexican drugstore online: purple pharmacy mexico price list – reputable mexican pharmacies online

canadianpharmacyworld com: onlinecanadianpharmacy 24 – canadian online pharmacy

indianpharmacy com canadian pharmacy india or top 10 pharmacies in india

http://stewardcreations.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=indiamedicine.world mail order pharmacy india

top 10 pharmacies in india india online pharmacy and indian pharmacy paypal canadian pharmacy india

http://gabapentin.pro/# neurontin 100 mg

zithromax prescription online buy generic zithromax no prescription or purchase zithromax online

http://mchawaii-interactonline.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=azithromycin.men zithromax 500 price

buy zithromax 500mg online zithromax for sale 500 mg and can i buy zithromax online can i buy zithromax online

neurontin 300 600 mg neurontin capsules 100mg neurontin prescription cost

https://stromectolonline.pro/# buy liquid ivermectin

over the counter neurontin neurontin 600 mg cost or neurontin price uk

http://viewthrume.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=gabapentin.pro neurontin 300 600 mg

neurontin 800 mg price buy gabapentin online and neurontin price neurontin 300 mg price in india

where to buy neurontin: neurontin pills – neurontin 300 600 mg

neurontin tablets 300 mg prescription drug neurontin or neurontin prices

http://biofest.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=gabapentin.pro neurontin online pharmacy

neurontin 3 neurontin 800 pill and neurontin 600 neurontin 600 mg

http://azithromycin.men/# generic zithromax india

ivermectin lice ivermectin drug or buy ivermectin

https://forum.83metoo.de/link.php?url=stromectolonline.pro ivermectin tablets uk

ivermectin 5 mg ivermectin cost canada and ivermectin 9 mg ivermectin 1% cream generic

neurontin 800 mg cost neurontin 300 mg tablets or neurontin 200

http://hollywoodredcarpetawards.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=gabapentin.pro generic neurontin cost

neurontin 400 mg capsules buy neurontin 300 mg and neurontin 300mg tablet cost neurontin 600 mg cost

neurontin 600 mg coupon: neurontin cost australia – buy neurontin uk

https://azithromycin.men/# zithromax online no prescription

zithromax 500mg price zithromax prescription online can you buy zithromax over the counter

https://stromectolonline.pro/# ivermectin nz

buy zithromax no prescription can you buy zithromax over the counter in australia or can i buy zithromax online

http://propertyiq.info/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=azithromycin.men zithromax cost australia

zithromax order online uk cost of generic zithromax and generic zithromax online paypal zithromax for sale us

ivermectin topical: ivermectin purchase – ivermectin 50ml

https://gabapentin.pro/# neurontin 1000 mg

neurontin for sale online purchase neurontin canada or buy cheap neurontin online

http://classificationfolders.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=gabapentin.pro neurontin 4000 mg

neurontin 200 mg capsules order neurontin over the counter and gabapentin 300mg how much is generic neurontin

ed meds best ed pills at gnc or erectile dysfunction drug

http://tceverywhere.tv/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=ed-pills.men impotence pills

erection pills viagra online ed pills gnc and male erection pills male ed drugs

https://antibiotic.guru/# Over the counter antibiotics pills

buy antibiotics from canada: buy antibiotics from canada – buy antibiotics online

https://paxlovid.top/# paxlovid pharmacy

compare ed drugs cheap erectile dysfunction pill or erectile dysfunction medications

http://crestron-test.us/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=ed-pills.men ed pills that really work

buy ed pills what are ed drugs and cheap erectile dysfunction pills online cure ed

paxlovid generic: paxlovid price – paxlovid price

paxlovid buy Paxlovid over the counter or paxlovid cost without insurance

http://promethean-casket.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=paxlovid.top Paxlovid over the counter

paxlovid india paxlovid covid and Paxlovid buy online paxlovid pharmacy

http://lipitor.pro/# lipitor australia

http://lisinopril.pro/# lisinopril with out prescription

lisinopril 50 mg: lisinopril price 10 mg – lisinopril 2.5 mg cost

https://avodart.pro/# can you buy generic avodart without a prescription

ciprofloxacin over the counter purchase cipro buy ciprofloxacin

https://lipitor.pro/# lipitor 40 mg tablet

where can i get avodart without rx buy generic avodart pills cost avodart without rx

https://lisinopril.pro/# lisinopril without rx

https://avodart.pro/# can you get cheap avodart

buy cipro online canada: buy generic ciprofloxacin – ciprofloxacin generic

http://ciprofloxacin.ink/# buy cipro online canada

lisinopril medication generic lisinopril in mexico can you order lisinopril online

how to get generic avodart without rx how can i get cheap avodart no prescription or avodart prices

http://tomboftheunknowns.org/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=avodart.pro how to buy generic avodart without a prescription

where to get generic avodart prices can you get avodart online and cost of avodart without dr prescription cost avodart prices

order lipitor online price of lipitor in india or lipitor generic brand name

http://howisyourheelpain.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=lipitor.pro generic lipitor for sale

lipitor 10mg price singapore best price for generic lipitor and lipitor generic india brand name lipitor price

cytotec pills buy online order cytotec online or buy cytotec over the counter

http://accountopen.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=misoprostol.guru п»їcytotec pills online

buy cytotec over the counter buy cytotec in usa and buy cytotec online buy cytotec over the counter

http://ciprofloxacin.ink/# ciprofloxacin generic

http://misoprostol.guru/# п»їcytotec pills online

http://avodart.pro/# can you buy avodart

buy generic lipitor lipitor lipitor

buy ciprofloxacin over the counter cipro for sale or cipro pharmacy

http://howlettfirm.net/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=ciprofloxacin.ink cipro pharmacy

ciprofloxacin 500 mg tablet price ciprofloxacin 500 mg tablet price and cipro 500mg best prices where can i buy cipro online

https://ciprofloxacin.ink/# ciprofloxacin order online

https://lisinopril.pro/# lisinopril 40 mg canada

http://misoprostol.guru/# buy cytotec in usa

lisinopril pill 10mg generic zestril lisinopril 20 mg pill

order generic avodart price how can i get avodart for sale or can i order cheap avodart no prescription

http://executiveluxuryhomes.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=avodart.pro where to get avodart pills

can i get avodart order cheap avodart no prescription and how to get cheap avodart without rx buy cheap avodart without a prescription

lipitor price drop lipitor brand name or lipitor 40 mg price in india

http://fibrasendero.net/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=lipitor.pro buy generic lipitor

lipitor 20mg cheap lipitor generic and lipitor generic online pharmacy cost of lipitor in canada

buy cytotec pills buy misoprostol over the counter or buy cytotec online

http://resolution1.es/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=misoprostol.guru Abortion pills online

purchase cytotec buy cytotec online fast delivery and Abortion pills online buy cytotec in usa

https://misoprostol.guru/# buy cytotec online fast delivery

https://avodart.pro/# can i purchase generic avodart prices

http://lipitor.pro/# lipitor 80 mg daily

cipro for sale ciprofloxacin order online buy generic ciprofloxacin

pharmacy canadian canadian pharmacy world or canadian pharmacy

http://chnrx.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=certifiedcanadapills.pro online canadian pharmacy

onlinecanadianpharmacy 24 certified canadian international pharmacy and canadian pharmacy tampa reputable canadian pharmacy

best online canadian pharmacy canadianpharmacymeds com or best rated canadian pharmacy

http://juventa.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=certifiedcanadapills.pro pharmacy rx world canada

cheap canadian pharmacy pharmacy canadian superstore and northwest pharmacy canada canadian pharmacy online ship to usa

pharmacies in mexico that ship to usa: п»їbest mexican online pharmacies – mexico pharmacies prescription drugs

https://certifiedcanadapills.pro/# canadian world pharmacy

canadian pharmacy ltd: canada ed drugs – canada online pharmacy

canadian family pharmacy legitimate canadian online pharmacies precription drugs from canada

when does cialis patent expire howard stern commercial cialis or to buy cialis generic

http://surfvermont.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=cialis.science cialis indien bezahlung mit paypal

cialis without prescriptions australia us cialis purchase and generic cialis cialis 20 mg

cheap kamagra cheap kamagra or buy kamagra online

http://charlottesvillevaattorneys.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=kamagra.men> cheap kamagra

order kamagra oral jelly kamagra and cheap kamagra kamagra

buy ed pills online best male ed pills or best erectile dysfunction pills

http://xambu.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=edpill.men ed medications

best otc ed pills best erection pills and generic ed drugs ed remedies

Kamagra tablets 100mg buy kamagra or buy kamagra

http://www.high-pressure-pumps.net/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=kamagra.men Kamagra Oral Jelly buy online

Kamagra tablets 100mg Kamagra tablets and Kamagra Oral Jelly buy online order kamagra oral jelly

where can i buy neurontin online neurontin cost in canada or buy neurontin 100 mg

http://divorcejusticecenter.net/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=gabapentin.tech neurontin tablets no script

canada neurontin 100mg discount how to get neurontin cheap and neurontin brand name neurontin prescription medication

where to buy ivermectin ivermectin over the counter canada or п»їorder stromectol online

http://www.tiffanyshow.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=ivermectin.auction ivermectin oral

ivermectin 8000 ivermectin rx and stromectol ivermectin 3 mg ivermectin oral 0 8

ivermectin buy ivermectin drug or where to buy stromectol online

http://xxxratedamateurs.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=ivermectin.auction stromectol where to buy

where to buy ivermectin purchase ivermectin and cost of ivermectin 1% cream stromectol online pharmacy

ivermectin usa stromectol covid or ivermectin buy australia

http://icvmcreative.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=ivermectin.today stromectol tablets buy online

ivermectin 8 mg stromectol usa and ivermectin purchase ivermectin generic name

ivermectin pills canada ivermectin brand name or stromectol buy uk

http://intoitmusic.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=ivermectin.today stromectol 0.5 mg

buy stromectol stromectol coronavirus and ivermectin cream 5% ivermectin 3 mg tabs

ivermectin 10 ml ivermectin 3 mg or ivermectin brand name

http://movingcontainerrental.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=ivermectin.today ivermectin buy

stromectol online stromectol for humans and where to buy stromectol online п»їorder stromectol online

buy stromectol uk stromectol ivermectin or ivermectin uk coronavirus

http://healthactuary.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=ivermectin.today ivermectin topical

ivermectin price ivermectin buy and ivermectin 1 topical cream buy stromectol online

ivermectin human cost of ivermectin medicine or ivermectin buy online

http://craftbeerhall.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=ivermectin.auction can you buy stromectol over the counter

ivermectin usa ivermectin where to buy and ivermectin coronavirus ivermectin 3mg tablets price

furosemide 40mg lasix generic name or lasix 40 mg

http://value-line.net/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=lasixfurosemide.store lasix generic

lasix 40 mg lasix dosage and lasix 20 mg lasix tablet

gabapentin order neurontin over the counter or gabapentin 300mg

http://fixedworld.it/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=gabamed.store neurontin price

neurontin prescription online buy neurontin 100 mg canada and neurontin 400 mg tablets neurontin price

ivermectin pill cost ivermectin tablets uk or ivermectin 6

http://davemacloed.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=ivermectinpharmacy.best stromectol 15 mg

stromectol 3mg tablets ivermectin canada and ivermectin topical ivermectin topical

world pharmacy india top online pharmacy india or top 10 online pharmacy in india

http://adslotonline.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=indiaph.ink top 10 pharmacies in india

cheapest online pharmacy india indian pharmacies safe and world pharmacy india best online pharmacy india

recommended canadian pharmacies safe canadian pharmacy or canadian pharmacy meds

http://sexybynight.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=canadaph.pro canadian pharmacy ltd

canadian mail order pharmacy reddit canadian pharmacy and trustworthy canadian pharmacy canadian mail order pharmacy

prescription drugs canada buy online safe canadian pharmacy or canadian pharmacy online reviews

http://nup98hoxd13.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=canadaph.pro trusted canadian pharmacy

online canadian pharmacy canada rx pharmacy and canadian pharmacies compare online canadian drugstore

top 10 online pharmacy in india: п»їlegitimate online pharmacies india – п»їlegitimate online pharmacies india

reputable canadian pharmacy: certified online pharmacy canada – buy canadian drugs

mexico drug stores pharmacies buying from online mexican pharmacy or mexican rx online

http://trashtocash.tv/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=mexicoph.icu best online pharmacies in mexico

mexico pharmacies prescription drugs buying prescription drugs in mexico and mexico drug stores pharmacies medicine in mexico pharmacies

canada online pharmacies pharmacy no perscription or pharm store canada

http://princessnail.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=interpharm.pro online pharmacy in india

online doctor prescription canada canada meds com and purchasing prescription drugs online top canadian pharmacies

mexico pharmacy online drugstore online pharmacy without prescription candaian pharmacies

licensed canadian pharmacy quality prescription drugs canada or safest canadian online pharmacy

http://factstuitionmanagement.org/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=interpharm.pro candian pharmacys

top canadian pharmacies recommended canadian online pharmacies and international pharmacy online pharmacy rx world com

best online canadian pharmacy prescription canada or buy medication online no prescription

http://northwoodscap.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=internationalpharmacy.icu no prescription online pharmacy

meds no prescription canada world pharmacy and canadian and international rx service trusted online pharmacies

canadian certified pharmacies buy drugs online without prescription or buy drugs online no prescription

http://drivermanagement.org/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=internationalpharmacy.icu online pharmacies no prescription

candian online pharmacy canadia pharmacy and canadian drugstores buy medications without a prescription

online pharmacy canada your canada drug store or canadian online pharmacy

http://xerionpartners.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=internationalpharmacy.icu no prescription drugs online

legit canadian pharmacy online pharmacy-canada and canada online pharmacy cheapest pharmacy online

pharmacy no perscription pharmacy rx world canada or canada pharmacys

http://blackboardasp.biz/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=internationalpharmacy.icu no perscription pharmacy

best online pharmacy without prescription best overseas pharmacy and mexico pharmacy online drugstore best international pharmacy

canada mail order prescriptions pharmacy canada or rate canadian pharmacy online

http://kenfisher.info/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=internationalpharmacy.icu most reliable canadian online pharmacy

rx from canada top mail order pharmacies and citrus ortho and joint institute rx from canada

drug stores in canada canadian pharmacy prescription or safe canadian pharmacies

http://rogerandsusanhertog.org/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=interpharm.pro no perscription needed

[url=http://comfortscience.org/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=interpharm.pro]buy drugs without prescription[/url] canada prescription and [url=http://bbs.cheaa.com/home.php?mod=space&uid=2960446]canadian pharmacy world review[/url] pharmacies in canada

http://onlineapotheke.tech/# online-apotheken

farmacia online acquistare farmaci senza ricetta or п»їfarmacia online migliore

http://hardwoodpurchasinghdbk.net/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=farmaciaonline.men farmaci senza ricetta elenco

acquisto farmaci con ricetta farmacia online and comprare farmaci online all’estero acquisto farmaci con ricetta

farmacia online barata farmacias online baratas or farmacia online barata

http://jesusfamilyreunion.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=farmaciabarata.pro farmacia barata

farmacias online baratas farmacias online seguras en espaГ±a and farmacia barata п»їfarmacia online

п»їpharmacie en ligne Pharmacie en ligne livraison 24h or Acheter mГ©dicaments sans ordonnance sur internet

http://hana-ranch.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=pharmacieenligne.icu Pharmacie en ligne sans ordonnance

Pharmacie en ligne livraison gratuite Pharmacie en ligne fiable and Pharmacie en ligne livraison gratuite Pharmacie en ligne pas cher

versandapotheke versandkostenfrei online apotheke deutschland or versandapotheke deutschland

http://ctasecurity.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=onlineapotheke.tech versandapotheke

online apotheke versandkostenfrei online apotheke gГјnstig and versandapotheke gГјnstige online apotheke

http://onlineapotheke.tech/# versandapotheke

п»їfarmacia online farmacias online seguras en espaГ±a farmacia online madrid

https://farmaciaonline.men/# farmacia online migliore

https://esfarmacia.men/# farmacia barata

pharmacie ouverte 24/24 – Pharmacie en ligne sans ordonnance

pharmacie ouverte 24/24 Acheter mГ©dicaments sans ordonnance sur internet or Acheter mГ©dicaments sans ordonnance sur internet

http://staging.pro/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=edpharmacie.pro Pharmacie en ligne pas cher

acheter mГ©dicaments Г l’Г©tranger acheter mГ©dicaments Г l’Г©tranger and pharmacie ouverte Pharmacie en ligne livraison 24h

farmacias online seguras farmacias online baratas or farmacia online internacional

http://yoursupermarket.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=esfarmacia.men farmacia envГos internacionales

п»їfarmacia online farmacia online barata and farmacia 24h farmacias online baratas

farmaci senza ricetta elenco farmacia online piГ№ conveniente or acquistare farmaci senza ricetta

http://ww35.osiemoats.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=itfarmacia.pro acquisto farmaci con ricetta

farmacia online senza ricetta acquistare farmaci senza ricetta and farmacie on line spedizione gratuita farmacie online sicure

https://edapotheke.store/# gГјnstige online apotheke

Viagra sans ordonnance 24h

gГјnstige online apotheke internet apotheke or versandapotheke

http://designvision.net/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=edapotheke.store п»їonline apotheke

online apotheke gГјnstig online apotheke versandkostenfrei and online apotheke preisvergleich online apotheke preisvergleich

https://edapotheke.store/# versandapotheke versandkostenfrei

reputable indian online pharmacy indian pharmacy or buy medicines online in india

http://stopsignstickers.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=indiapharm.cheap indian pharmacies safe

mail order pharmacy india reputable indian online pharmacy and buy medicines online in india indian pharmacies safe

mexico pharmacies prescription drugs: best online pharmacies in mexico – mexican rx online

canadian pharmacy phone number canada rx pharmacy or my canadian pharmacy

http://caytonconcrete.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=canadapharm.store canadian drugs

canadian pharmacy 24h com is canadian pharmacy legit and my canadian pharmacy canadian drugs

canadian pharmacies comparison canadian valley pharmacy or canadian drug

http://globalcitizens.biz/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=canadapharm.store best canadian pharmacy

best canadian online pharmacy reviews canadian online drugs and canada discount pharmacy pharmacies in canada that ship to the us

mexican pharmaceuticals online mexico drug stores pharmacies or buying prescription drugs in mexico online

http://self-healingfileserver.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=mexicopharm.store mexican mail order pharmacies

mexican rx online pharmacies in mexico that ship to usa and mexican rx online mexican online pharmacies prescription drugs

The staff provides excellent advice on over-the-counter choices. mexican online pharmacies prescription drugs: mexican rx online – purple pharmacy mexico price list

pharmacy canadian superstore: canadian king pharmacy – pharmacy rx world canada

best canadian pharmacy online: canada online pharmacy – ed drugs online from canada

They consistently exceed global healthcare expectations. india online pharmacy: online pharmacy india – п»їlegitimate online pharmacies india

mail order pharmacy india buy medicines online in india or п»їlegitimate online pharmacies india

http://berkshirehathawayofcharlotterealestate.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=indiapharm.cheap Online medicine home delivery

top 10 pharmacies in india best online pharmacy india and india pharmacy mail order pharmacy website india

ed meds online canada safe canadian pharmacy or canadian drug

http://allalphabet.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=canadapharm.store cheapest pharmacy canada

global pharmacy canada the canadian pharmacy and real canadian pharmacy rate canadian pharmacies

mexican drugstore online: purple pharmacy mexico price list – buying from online mexican pharmacy

п»їbest mexican online pharmacies buying prescription drugs in mexico or purple pharmacy mexico price list

http://studionavigator.org/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=mexicopharm.store mexican pharmaceuticals online

pharmacies in mexico that ship to usa purple pharmacy mexico price list and mexico pharmacies prescription drugs mexico pharmacies prescription drugs

legal to buy prescription drugs from canada ed drugs online from canada or pharmacy rx world canada

http://brainy-store.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=canadapharm.store canada pharmacy online

pharmacy rx world canada online canadian pharmacy reviews and canadian pharmacy online ship to usa canadian pharmacy online ship to usa

The best in town, without a doubt. india online pharmacy: online pharmacy india – best online pharmacy india

Online medicine home delivery: best online pharmacy india – indian pharmacy

Get here. http://azithromycinotc.store/# zithromax prescription online

zithromax 500 mg lowest price pharmacy online buy Z-Pak online zithromax 250

http://edpillsotc.store/# impotence pills

A name synonymous with international pharmaceutical trust. https://doxycyclineotc.store/# doxycycline uk cost

how to buy zithromax online generic zithromax over the counter or zithromax canadian pharmacy

http://mommiedearest.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=azithromycinotc.store generic zithromax 500mg

zithromax 500mg how to get zithromax and buy zithromax online with mastercard zithromax over the counter uk

ed meds best ed pill or non prescription ed pills

http://chamberexec.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=edpillsotc.store buying ed pills online

men’s ed pills cheapest ed pills and ed pill best otc ed pills

ed treatments ed meds or ed pills for sale

http://teuladamoraira.es/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=edpillsotc.store top ed pills

ed pills online treatments for ed and best ed pills non prescription best ed drug

Their commitment to global excellence is unwavering. http://doxycyclineotc.store/# doxycycline pharmacy

medicine doxycycline 100mg can you buy doxycycline over the counter nz or doxycycline 100mg tablets coupon

http://vistavitamins.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=doxycyclineotc.store buy doxycycline 100mg online uk

doxycycline price comparison doxycycline prescription cost and doxycycline 125 mg doxycyline

generic zithromax over the counter cheap zithromax pills where to get zithromax

They understand the intricacies of international drug regulations. zithromax cost: buy azithromycin over the counter – zithromax 500 without prescription

Their multilingual support team is a blessing. http://azithromycinotc.store/# buy zithromax 1000 mg online

Efficient, effective, and always eager to assist. https://drugsotc.pro/# canadian compounding pharmacy

I’m always impressed with their efficient system. https://drugsotc.pro/# mexican pharmacy online

top online pharmacy india reputable indian pharmacies or world pharmacy india

http://directbuywines.net/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=indianpharmacy.life top 10 online pharmacy in india

india online pharmacy top 10 online pharmacy in india and top 10 online pharmacy in india buy prescription drugs from india

Their health awareness programs are game-changers. https://drugsotc.pro/# cheapest pharmacy for prescription drugs

mexican pharmaceuticals online buying prescription drugs in mexico online or mexican mail order pharmacies

http://welchconsulting.info/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=mexicanpharmacy.site buying from online mexican pharmacy

mexican mail order pharmacies mexican online pharmacies prescription drugs and mexican pharmaceuticals online mexican border pharmacies shipping to usa

pharmacy discount coupons international pharmacy no prescription or canada rx pharmacy

http://primoshoagies.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=drugsotc.pro reputable overseas online pharmacies

tadalafil canadian pharmacy best india pharmacy and www canadianonlinepharmacy the canadian pharmacy

canada pharmacy online legit canadian pharmacy without prescription on line pharmacy

Their global distribution network is top-tier. http://drugsotc.pro/# online pharmacy 365

legitimate canadian online pharmacies rate online pharmacies or canadian pharmacy india

http://www.financetemp.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=drugsotc.pro best india pharmacy

canadian pharmacy 24 northwest canadian pharmacy and express pharmacy canadadrugpharmacy com

They set the tone for international pharmaceutical excellence. https://drugsotc.pro/# canadian pharmacy no prescription

top online pharmacy india buy prescription drugs from india or world pharmacy india

http://mmorig.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=indianpharmacy.life cheapest online pharmacy india

best india pharmacy top 10 online pharmacy in india and п»їlegitimate online pharmacies india pharmacy website india

india pharmacy Mail order pharmacy India top online pharmacy india

They ensure global standards in every pill. https://indianpharmacy.life/# buy prescription drugs from india

canadianpharmacymeds com buying from canadian pharmacies or canadian pharmacy without prescription

http://www.gsaschedulemanual.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=drugsotc.pro brazilian pharmacy online

reputable online pharmacy no prescription vipps canadian pharmacy and pharmacy canadian canadian pharmacy viagra 50 mg

mexico drug stores pharmacies п»їbest mexican online pharmacies or mexico pharmacies prescription drugs

http://fwf1.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=mexicanpharmacy.site mexican pharmaceuticals online

medication from mexico pharmacy purple pharmacy mexico price list and mexico drug stores pharmacies mexican drugstore online

prescription drugs online mexican pharmacy or pharmacy no prescription required

http://bitterrootmontana.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=drugsotc.pro safe online pharmacies in canada

pharmacy near me 24 hours pharmacy and online pharmacy price checker canada drug pharmacy

Consistent excellence across continents. http://mexicanpharmacy.site/# mexican pharmaceuticals online

mexican online pharmacies prescription drugs mexican online pharmacy pharmacies in mexico that ship to usa

canada pharmacy online: cheap drugs from canada – legitimate canadian pharmacy online

top pills online pharmacy best online pharmacy no prescription or india pharmacy online

http://yanbalintl.net/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=internationalpharmacy.pro pharmacy on line canada

canadian rx prescription drugstore medicine with no prescription and mexico pharmacy online drugstore canidian pharmacy

buy prescription drugs from canada cheap onlinepharmaciescanada com or certified canadian international pharmacy

http://thestemcellmarket.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=canadapharmacy.cheap thecanadianpharmacy

canadian pharmacy 365 canadapharmacyonline com and canadian pharmacy near me canadian pharmacy service

canada online pharmacy legitimate: online pharmacies without prescription – canadianpharmacyonline

Always a pleasant experience at this pharmacy. http://gabapentin.world/# brand name neurontin price

vipps approved canadian online pharmacy canadian pharmacy antibiotics or canadadrugpharmacy com

https://www.exyst.de/domain_check_whois.php?query=canadapharmacy.cheap& reddit canadian pharmacy

best canadian online pharmacy reviews canada drugs online review and legit canadian pharmacy online canada rx pharmacy

mexican pharmaceuticals online and mexican pharmacies – mexico drug stores pharmacies

I’ve sourced rare medications thanks to their global network. https://mexicanpharmonline.com/# mexican pharmaceuticals online

purple pharmacy mexico price list mexico pharmacy mexican pharmaceuticals online

mexican online pharmacies prescription drugs and mexico online pharmacy – medication from mexico pharmacy

mexican rx online mexican drugstore online or buying prescription drugs in mexico online

http://economad.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=mexicanpharmonline.com mexican online pharmacies prescription drugs

п»їbest mexican online pharmacies purple pharmacy mexico price list and mexico pharmacy buying prescription drugs in mexico

mexican online pharmacies prescription drugs buying prescription drugs in mexico or reputable mexican pharmacies online

http://opticair.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=mexicanpharmonline.shop mexican mail order pharmacies

mexico pharmacies prescription drugs medication from mexico pharmacy and medicine in mexico pharmacies best online pharmacies in mexico

purple pharmacy mexico price list mexican mail order pharmacies or mexican online pharmacies prescription drugs

http://www.the-phillips-collection.net/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=mexicanpharmonline.shop medicine in mexico pharmacies

reputable mexican pharmacies online buying prescription drugs in mexico and mexican mail order pharmacies buying from online mexican pharmacy

Always up-to-date with international medical advancements. http://mexicanpharmonline.com/# medication from mexico pharmacy

mexican pharmaceuticals online mexico pharmacy mexican online pharmacies prescription drugs

mexican online pharmacies prescription drugs and mexico pharmacy – pharmacies in mexico that ship to usa

buying prescription drugs in mexico – mexico online pharmacy – buying prescription drugs in mexico

Always ahead of the curve with global healthcare trends. https://mexicanpharmonline.shop/# pharmacies in mexico that ship to usa

mexico drug stores pharmacies mexican pharmacy purple pharmacy mexico price list

mexico drug stores pharmacies or pharmacy in mexico – buying prescription drugs in mexico

buying prescription drugs in mexico mexican drugstore online or mexican online pharmacies prescription drugs

http://angels-rehab.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=mexicanpharmonline.shop reputable mexican pharmacies online

pharmacies in mexico that ship to usa medication from mexico pharmacy and buying prescription drugs in mexico pharmacies in mexico that ship to usa

real canadian pharmacy: canada pharmacy – canadian pharmacy in canada

https://stromectol24.pro/# minocycline 100 mg without a doctor

indian pharmacies safe buy medicines online in india or reputable indian pharmacies

http://saudidigitalhistory.info/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=indiapharmacy24.pro india pharmacy

best online pharmacy india online shopping pharmacy india and top 10 online pharmacy in india top online pharmacy india

canadian pharmacy store canada drugstore pharmacy rx or canadian drug stores

http://minute-deals.net/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=canadapharmacy24.pro northwest canadian pharmacy

canada pharmacy reviews canadian drug pharmacy and best rated canadian pharmacy canadian 24 hour pharmacy

reputable indian pharmacies: cheapest online pharmacy india – indian pharmacy

minocycline 100 mg otc minocycline capsule or minocycline 100mg online

http://www.baherbs.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=stromectol24.pro ivermectin buy uk

ivermectin virus ivermectin human and ivermectin generic cream minocycline 100mg tablets for human

https://canadapharmacy24.pro/# best mail order pharmacy canada

best canadian pharmacy: canadian pharmacy online 24 pro – online canadian pharmacy

http://stromectol24.pro/# ivermectin eye drops

cheapest online pharmacy india indian pharmacy online or india online pharmacy

http://clhiii.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=indiapharmacy24.pro mail order pharmacy india

top 10 pharmacies in india world pharmacy india and top 10 pharmacies in india online shopping pharmacy india

canadian pharmacy meds: best pharmacy online – legit canadian pharmacy

buy minocycline 50 mg for humans buy minocycline 50 mg tablets or ivermectin 1% cream generic

http://leasingperu.net/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=stromectol24.pro п»їwhere to buy stromectol online

ivermectin 200 minocycline 50 mg without a doctor and ivermectin 2mg ivermectin 10 mg

canada pharmacy world reddit canadian pharmacy or ed drugs online from canada

http://maximummaximiles.net/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=canadapharmacy24.pro canadian pharmacy victoza

recommended canadian pharmacies canadian online drugs and canadian pharmacy near me buying from canadian pharmacies

http://indiapharmacy24.pro/# indian pharmacy paypal

https://plavix.guru/# buy clopidogrel online

п»їplavix generic: Plavix 75 mg price – buy clopidogrel online

http://mobic.icu/# mobic medication

paxlovid cost without insurance antiviral paxlovid pill п»їpaxlovid

http://paxlovid.bid/# paxlovid for sale

paxlovid price: nirmatrelvir and ritonavir online – paxlovid price

http://valtrex.auction/# valtrex pills for sale

paxlovid pharmacy paxlovid covid paxlovid generic

buy Clopidogrel over the counter Cost of Plavix on Medicare or buy Clopidogrel over the counter

http://dexterlions.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=plavix.guru buy clopidogrel online

buy clopidogrel bisulfate Clopidogrel 75 MG price and buy plavix plavix best price

ivermectin 4000 minocycline 50mg without doctor or minocycline coupon

http://qatarpharma.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=stromectol.icu minocycline 50

does minocycline cause weight gain stromectol 3 mg tablet and minocycline 50mg tablets online minocycline 50 mg without prescription

paxlovid pill: antiviral paxlovid pill – paxlovid pharmacy

paxlovid cost without insurance paxlovid covid or Paxlovid buy online

http://examiner-enterprise.co/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=paxlovid.bid paxlovid india

paxlovid buy paxlovid india and paxlovid cost without insurance paxlovid generic

buy valtrex online mexico valtrex discount or valtrex 2000 mg

http://dr-shrink.biz/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=valtrex.auction can you order valtrex online

cheap valtrex online price of valtrex in india and otc valtrex for sale valtrex cost india

where can i buy generic mobic no prescription: buy anti-inflammatory drug – how can i get cheap mobic price

http://paxlovid.bid/# paxlovid for sale

get cheap mobic prices: Mobic meloxicam best price – cost of generic mobic prices

https://mobic.icu/# where to get mobic without rx

plavix medication п»їplavix generic generic plavix

generic mobic: cheap meloxicam – can i buy cheap mobic without insurance

how can i get cheap mobic without dr prescription: cheap meloxicam – can i purchase mobic pill

https://plavix.guru/# buy clopidogrel bisulfate

paxlovid covid paxlovid pharmacy or paxlovid for sale

http://sunspectrum.net/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=paxlovid.bid п»їpaxlovid

paxlovid pill paxlovid for sale and paxlovid for sale п»їpaxlovid

paxlovid pharmacy: nirmatrelvir and ritonavir online – п»їpaxlovid

https://valtrex.auction/# how can i get valtrex

valtrex generic over the counter valtrex antiviral drug buy generic valtrex cheap

http://levitra.eus/# Generic Levitra 20mg

cialis for sale Buy Tadalafil 10mg Buy Cialis online

buy kamagra online usa Kamagra Oral Jelly or Kamagra Oral Jelly

http://poultrycoolingnozzles.info/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=kamagra.icu Kamagra 100mg price

Kamagra tablets Kamagra 100mg price and super kamagra super kamagra

http://levitra.eus/# Buy Vardenafil 20mg online

https://kamagra.icu/# Kamagra tablets

Generic Cialis price Tadalafil price or Buy Cialis online

http://resourcemothers.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=cialis.foundation Buy Tadalafil 20mg

Tadalafil Tablet Generic Tadalafil 20mg price and Cheap Cialis cheapest cialis

Viagra without a doctor prescription Canada Cheap Viagra 100mg or Viagra online price

http://naturalgelimplant.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=viagra.eus Viagra without a doctor prescription Canada

[url=http://irishorizons.net/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=viagra.eus]sildenafil 50 mg price[/url] Cheap Viagra 100mg and [url=http://talk.dofun.cc/home.php?mod=space&uid=9686]Generic Viagra for sale[/url] sildenafil over the counter

https://kamagra.icu/# Kamagra 100mg

Buy Levitra 20mg online п»їLevitra price Levitra 20 mg for sale

http://cialis.foundation/# Cheap Cialis

Every weekend i used to visit this site, because i want enjoyment, as this this web page conations truly good funny data too.

https://miobi.ee/listing-category/torgovlja/

Cheap Levitra online Levitra 20 mg for sale Levitra generic best price

Buy Tadalafil 5mg Tadalafil price or Tadalafil Tablet

http://synergistic.us/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=cialis.foundation Cialis without a doctor prescription

buy cialis pill Generic Cialis price and Generic Tadalafil 20mg price п»їcialis generic

Viagra without a doctor prescription Canada Viagra online price or buy Viagra online

http://polaredge.tv/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=viagra.eus generic sildenafil

viagra without prescription viagra without prescription and Viagra without a doctor prescription Canada Order Viagra 50 mg online

https://levitra.eus/# Cheap Levitra online

http://kamagra.icu/# buy Kamagra

http://kamagra.icu/# cheap kamagra

Cialis 20mg price in USA Buy Tadalafil 5mg Cialis over the counter

sildenafil oral jelly 100mg kamagra Kamagra tablets or buy Kamagra

http://mygtadvisors.biz/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=kamagra.icu Kamagra Oral Jelly

Kamagra 100mg Kamagra Oral Jelly and Kamagra 100mg price Kamagra Oral Jelly

https://cialis.foundation/# cheapest cialis

Cheapest Sildenafil online Buy generic 100mg Viagra online Buy Viagra online cheap

https://kamagra.icu/# cheap kamagra

cheapest cialis Cialis without a doctor prescription or Generic Cialis without a doctor prescription

http://shopperdiscountsrewardscam.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=cialis.foundation Generic Tadalafil 20mg price

Buy Tadalafil 20mg Generic Cialis price and Cialis 20mg price cialis for sale

http://kamagra.icu/# super kamagra

cialis for sale Tadalafil Tablet Generic Cialis price

http://kamagra.icu/# sildenafil oral jelly 100mg kamagra

https://viagra.eus/# sildenafil 50 mg price

buy cialis pill Generic Tadalafil 20mg price Cialis 20mg price in USA

https://indiapharmacy.pro/# reputable indian pharmacies indiapharmacy.pro

http://mexicanpharmacy.company/# buying from online mexican pharmacy mexicanpharmacy.company

п»їlegitimate online pharmacies india: п»їlegitimate online pharmacies india – reputable indian pharmacies indiapharmacy.pro

reputable indian online pharmacy indianpharmacy com top 10 online pharmacy in india indiapharmacy.pro

top 10 online pharmacy in india: top online pharmacy india – indian pharmacy indiapharmacy.pro

mexican pharmaceuticals online: medicine in mexico pharmacies – mexico pharmacies prescription drugs mexicanpharmacy.company

п»їlegitimate online pharmacies india: india pharmacy – indian pharmacy indiapharmacy.pro

reddit canadian pharmacy canada pharmacy online legit ed meds online canada canadapharmacy.guru

mexican online pharmacies prescription drugs: mexican online pharmacies prescription drugs – best online pharmacies in mexico mexicanpharmacy.company

indian pharmacy indian pharmacy online or top 10 pharmacies in india

http://www.pestcontrollerreport.net/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=indiapharmacy.pro mail order pharmacy india

top 10 online pharmacy in india top 10 pharmacies in india and best online pharmacy india pharmacy website india

http://canadapharmacy.guru/# trustworthy canadian pharmacy canadapharmacy.guru

legitimate canadian pharmacy canadian pharmacy drugs online or canadian pharmacy drugs online

http://drhaiken.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=canadapharmacy.guru canadian drugstore online

trustworthy canadian pharmacy canadian pharmacy tampa and adderall canadian pharmacy canadian pharmacy india

india pharmacy: online shopping pharmacy india – canadian pharmacy india indiapharmacy.pro

canadian discount pharmacy canadian 24 hour pharmacy canada rx pharmacy canadapharmacy.guru

https://mexicanpharmacy.company/# mexico pharmacies prescription drugs mexicanpharmacy.company

precription drugs from canada: the canadian drugstore – canadian drugstore online canadapharmacy.guru

best canadian pharmacy canadian drug stores or canada discount pharmacy

http://carnivalcashcard.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=canadapharmacy.guru canadian online pharmacy

best canadian pharmacy online onlinecanadianpharmacy and pharmacy in canada pharmacies in canada that ship to the us

mexican online pharmacies prescription drugs: buying prescription drugs in mexico online – mexican drugstore online mexicanpharmacy.company

top online pharmacy india: best online pharmacy india – best online pharmacy india indiapharmacy.pro

п»їlegitimate online pharmacies india cheapest online pharmacy india canadian pharmacy india indiapharmacy.pro

mexican border pharmacies shipping to usa mexican pharmaceuticals online or buying prescription drugs in mexico online

http://kenotravelrewards.net/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=mexicanpharmacy.company mexican online pharmacies prescription drugs

mexican drugstore online buying prescription drugs in mexico online and mexican pharmaceuticals online pharmacies in mexico that ship to usa

top 10 online pharmacy in india top online pharmacy india or п»їlegitimate online pharmacies india

http://johnsparling.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=indiapharmacy.pro pharmacy website india

india pharmacy india pharmacy mail order and buy prescription drugs from india online pharmacy india

http://indiapharmacy.pro/# online pharmacy india indiapharmacy.pro

my canadian pharmacy reviews: adderall canadian pharmacy – vipps canadian pharmacy canadapharmacy.guru

indian pharmacy paypal: indian pharmacy online – india pharmacy mail order indiapharmacy.pro

precription drugs from canada canadian pharmacy service canadian pharmacy no rx needed canadapharmacy.guru

https://canadapharmacy.guru/# reddit canadian pharmacy canadapharmacy.guru

indianpharmacy com: top 10 online pharmacy in india – п»їlegitimate online pharmacies india indiapharmacy.pro

https://canadapharmacy.guru/# canadian pharmacy antibiotics canadapharmacy.guru

reliable canadian pharmacy canada pharmacy or rate canadian pharmacies

http://beyondretirement.org/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=canadapharmacy.guru canadianpharmacymeds com

best canadian pharmacy to order from cheap canadian pharmacy and is canadian pharmacy legit reddit canadian pharmacy

buying from online mexican pharmacy: mexican rx online – purple pharmacy mexico price list mexicanpharmacy.company

pharmacy website india canadian pharmacy india best online pharmacy india indiapharmacy.pro

online pharmacy india: top online pharmacy india – top 10 online pharmacy in india indiapharmacy.pro

canada cloud pharmacy real canadian pharmacy or canadian drug stores

http://impactconsumerresearch.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=canadapharmacy.guru canadian pharmacy no scripts

pharmacy wholesalers canada medication canadian pharmacy and best rated canadian pharmacy canadian discount pharmacy

top 10 pharmacies in india top 10 online pharmacy in india or reputable indian pharmacies

http://axalife.biz/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=indiapharmacy.pro india online pharmacy

п»їlegitimate online pharmacies india online shopping pharmacy india and top 10 online pharmacy in india best online pharmacy india

mexican pharmaceuticals online reputable mexican pharmacies online or mexican rx online

http://sales-sherpa.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=mexicanpharmacy.company best online pharmacies in mexico

purple pharmacy mexico price list best online pharmacies in mexico and buying from online mexican pharmacy mexican online pharmacies prescription drugs

http://indiapharmacy.pro/# online pharmacy india indiapharmacy.pro

real canadian pharmacy: canadian king pharmacy – legit canadian pharmacy canadapharmacy.guru

canadian drug stores canadian pharmacy 24 canadian pharmacy online store canadapharmacy.guru

mexican pharmaceuticals online: mexican rx online – mexican mail order pharmacies mexicanpharmacy.company

http://indiapharmacy.pro/# india online pharmacy indiapharmacy.pro

medicine in mexico pharmacies: mexico pharmacy – mexico drug stores pharmacies mexicanpharmacy.company

https://mexicanpharmacy.company/# mexico pharmacies prescription drugs mexicanpharmacy.company

reputable mexican pharmacies online: medicine in mexico pharmacies – buying prescription drugs in mexico online mexicanpharmacy.company

77 canadian pharmacy canadian family pharmacy best canadian online pharmacy canadapharmacy.guru

mexican rx online: mexican online pharmacies prescription drugs – mexico drug stores pharmacies mexicanpharmacy.company

canada pharmacy world canadian pharmacy world or cheap canadian pharmacy

http://talktocousins.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=canadapharmacy.guru drugs from canada

canadian drug stores cross border pharmacy canada and canadian pharmacy uk delivery ordering drugs from canada

ed drugs online from canada canadian pharmacy no scripts or canadian online pharmacy

http://stuartschool.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=canadapharmacy.guru 77 canadian pharmacy

ordering drugs from canada canadian pharmacy scam and reputable canadian pharmacy my canadian pharmacy reviews

mexican drugstore online mexican border pharmacies shipping to usa or mexican drugstore online

http://bulletinboardpro.org/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=mexicanpharmacy.company buying prescription drugs in mexico online

[url=http://jimcolerealestate.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=mexicanpharmacy.company]buying prescription drugs in mexico online[/url] mexico drug stores pharmacies and [url=http://bbs.xinhaolian.com/home.php?mod=space&uid=2690770]mexican online pharmacies prescription drugs[/url] buying from online mexican pharmacy

https://mexicanpharmacy.company/# pharmacies in mexico that ship to usa mexicanpharmacy.company

mexican rx online: mexico drug stores pharmacies – medicine in mexico pharmacies mexicanpharmacy.company

buying from online mexican pharmacy mexican pharmaceuticals online reputable mexican pharmacies online mexicanpharmacy.company

mexican online pharmacies prescription drugs: medication from mexico pharmacy – buying from online mexican pharmacy mexicanpharmacy.company

Online medicine order: п»їlegitimate online pharmacies india – india pharmacy mail order indiapharmacy.pro

https://indiapharmacy.pro/# mail order pharmacy india indiapharmacy.pro

http://canadapharmacy.guru/# canadian pharmacy victoza canadapharmacy.guru

best online pharmacy india best india pharmacy or top 10 online pharmacy in india

http://thebestideasinmedicine.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=indiapharmacy.pro pharmacy website india

top 10 pharmacies in india top 10 online pharmacy in india and indian pharmacy paypal buy medicines online in india

reputable indian online pharmacy: indian pharmacy – reputable indian online pharmacy indiapharmacy.pro

http://indiapharmacy.pro/# india pharmacy mail order indiapharmacy.pro

mexico drug stores pharmacies buying from online mexican pharmacy or reputable mexican pharmacies online

http://letstalkwireless.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=mexicanpharmacy.company buying prescription drugs in mexico

buying prescription drugs in mexico pharmacies in mexico that ship to usa and mexican online pharmacies prescription drugs mexican online pharmacies prescription drugs

legal to buy prescription drugs from canada: canadian pharmacy price checker – canada rx pharmacy canadapharmacy.guru

canadian pharmacy tampa thecanadianpharmacy or www canadianonlinepharmacy

http://checkthelist.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=canadapharmacy.guru canadian pharmacy sarasota

onlinecanadianpharmacy 24 canadian world pharmacy and safe canadian pharmacies canadian pharmacy mall

canadian pharmacy price checker canadian pharmacy uk delivery or canadian discount pharmacy

http://danielmayo.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=canadapharmacy.guru canadian pharmacy 365

77 canadian pharmacy escrow pharmacy canada and legit canadian pharmacy canadian pharmacy

best canadian online pharmacy: canada pharmacy 24h – reputable canadian pharmacy canadapharmacy.guru

canadian pharmacy india reputable indian online pharmacy indianpharmacy com indiapharmacy.pro

http://mexicanpharmacy.company/# buying from online mexican pharmacy mexicanpharmacy.company

pharmacy canadian: best canadian pharmacy online – canadian pharmacy no rx needed canadapharmacy.guru

reputable indian online pharmacy online pharmacy india or india pharmacy

http://www.hystericalsociety.net/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=indiapharmacy.pro best online pharmacy india

mail order pharmacy india india pharmacy and buy prescription drugs from india п»їlegitimate online pharmacies india

safe online pharmacies in canada: canadianpharmacyworld com – canadian pharmacy antibiotics canadapharmacy.guru

india pharmacy mail order best online pharmacy india online shopping pharmacy india indiapharmacy.pro

canadian pharmacies compare: pharmacy canadian superstore – legit canadian pharmacy canadapharmacy.guru

http://canadapharmacy.guru/# canadian pharmacy no scripts canadapharmacy.guru

mexican online pharmacies prescription drugs buying prescription drugs in mexico or buying prescription drugs in mexico

http://plusproductions.us/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=mexicanpharmacy.company pharmacies in mexico that ship to usa

mexico drug stores pharmacies pharmacies in mexico that ship to usa and mexican online pharmacies prescription drugs mexican drugstore online

best canadian online pharmacy: canadian pharmacy online – legit canadian online pharmacy canadapharmacy.guru

safe canadian pharmacies: best canadian pharmacy – canada rx pharmacy canadapharmacy.guru

mexico drug stores pharmacies mexican mail order pharmacies best online pharmacies in mexico mexicanpharmacy.company

http://clomid.sbs/# where buy generic clomid price

prednisone 20mg price in india iv prednisone 50 mg prednisone tablet

cost of cheap propecia without dr prescription: buy cheap propecia pill – buy propecia

https://clomid.sbs/# cheap clomid without prescription

http://prednisone.digital/# buy prednisone 1 mg mexico

buy doxycycline online uk generic doxycycline doxycycline pills

doxycycline hyc: doxycycline without a prescription – doxycycline generic

https://propecia.sbs/# cost of propecia pills

amoxicillin 250 mg price in india: amoxicillin 775 mg – where to get amoxicillin over the counter

http://doxycycline.sbs/# buy doxycycline without prescription

buying cheap propecia without prescription buying propecia price propecia pill

propecia price: cost of generic propecia price – cost propecia no prescription